He may specialise in French cuisine, but Chef Phillippe Vanderwalle also knows how to rustle up a fine vintage enduro bike. In the shape of this 1978 KTM 400GS6….

Frenchman Phillippe Vanderwalle has two passions in life: cooking and vintage enduro bikes. The former has seen him leave his native Bordeaux, work for the famous Roux brothers and even (briefly) employ Gordon Ramsey, before taking up his current position as ‘Chef de Cuisine’ at London’s exclusive Ritz Club. The latter accounts for the exceptionally pretty 1978 Penton-KTM that was sitting-tall on its centrestand when we arrived at his east London home…

This wasn’t the first time we’d set eyes on the bike however, as whilst idly perusing the internet ‘researching’ last month’s vintage enduro feature we came across an advertisement for the orange machine. The asking price – a shade over three grand – reflects the time and expense that Phillippe has put into what started out as an £800 bitsa…

I would never describe it as a 20-yard bike as parts of it are absolutely immaculate, but get up-close and it’s obvious that Phillippe has ‘restored’ the bike to be ridden rather than sat in a showroom or trailered from show to show – the previous owner had painted the magnesium hubs silver and the spokes are covered in overspray, and underneath the beige paint the fork lowers show the signs of the odd stone-chip or two. Because although many of us are drawn to these old bikes purely because of their aesthetic qualities, Phillippe is very much part of a growing band of dirtbikers who regularly ride their classic machinery.

The bike is a 400 GS6, the ‘GS’ being short for GeländeSport (there’s not really a direct translation but it essentially means ‘enduro sport’) and the ‘6’ relating to the number of gears. 400 is actually a bit of a fib, as Phillippe explains that the heavily finned motor actually displaces closer to 350cc. ‘It’s still on its original 81mm bore, he remarked as he tickled the original Bing carb and swung out the articulated kickstart lever. Having clambered aboard the lofty seat – even higher when the bike is balanced on its centrestand – he pushed his bodyweight down through the whole stroke of the kicker and the bike immediately burst into life, before snuffing itself out after a few revolutions. The procedure was repeated, and again, and third time around the air-cooled motor finally caught and settled into the lovely ringa-ding-ding idle that old strokers are renowned.

‘I had a problem starting it’, reports Phillippe, referring to when he first put the bike back together, before explaining the reason behind a good deal of head-scratching; The Magura choke lever up on the chromed bars works the exact opposite of how you’d expect. Pull the lever and the choke is off, release it and the choke is on..!

Speaking of levers, the clutch lever requires a real ‘Bullworker’ squeeze in order to separate the plates, which Phillippe remembers ‘cost a fortune.’ Parts for the bike are still available if you know where to look (Austria mainly!), and there’s almost two grand’s worth of new bits ‘n’ pieces on the 400.

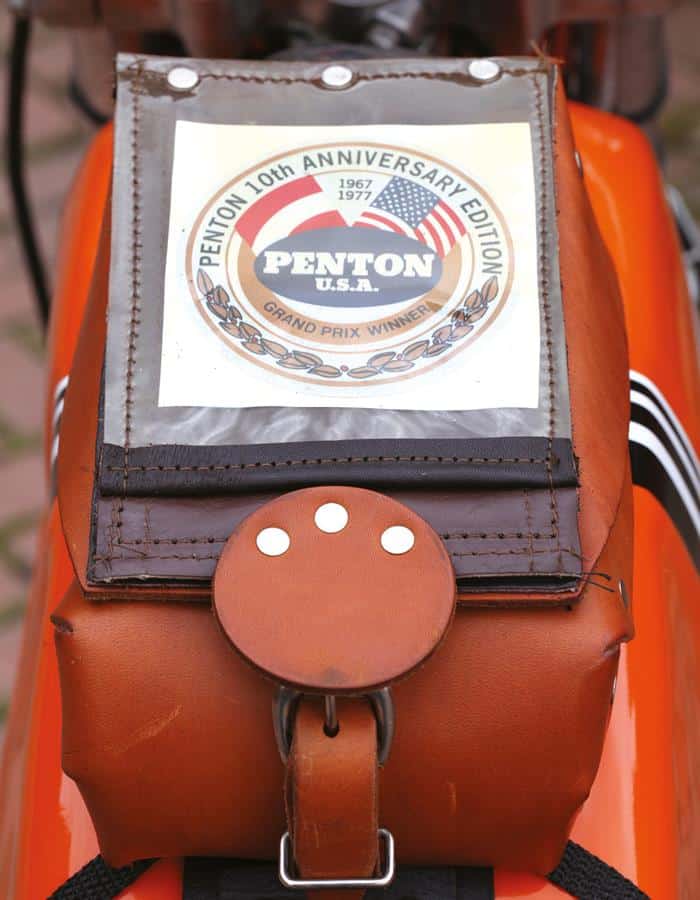

Some of those parts were replacements for tired originals, and others – such as the natty KTM-logo’d gaiters on the Magura levers and the brown leather toolbag – are there to add that certain something. Phillippe even sourced a ‘Hi-Point chrome-moly steel’ sticker for the frame. There’s a fine mix of restored and untouched original components too. The beautiful, finned Marzocchi shocks have been restored – as have the forks – and the tank has been resprayed, whilst the rubber ‘stops’ on the swingarm (to prevent the centrestand clanging against it) were carefully prised-off and refitted once the chassis had been painted. And the standard (and rather optimistic) 120mph speedo features a fine patina. Overall, the bike looks great, immaculate in all the right places but not so spotless that you wouldn’t want to actually use it.

‘It’s nice power, smooth, nothing like the infamous 495’, reports Phillippe, relating to the stupidly powerful motocrosser of the same era. ‘But in third gear the front wheel will still come up.’

Cooking Up a Storm

Back in the late ‘60s American John Penton approached KTM with the idea of producing a lightweight off-road machine. At the time the Austrians were busy producing mopeds and bicycles (indeed, there’s still a KTM bicycle company) though they duly agreed and, in 1968, produced a small-bore enduro bike which Penton could sell eponymously in the US. Elsewhere the bike was branded a KTM. With the launch of further models, this agreement continued until the end of 1977, thereafter the US-bound bikes also became KTMs.

The provenance of Phillippe’ 400 is a little hazy, mainly because it spans this transitional period. ‘The centre-stand and pegs are ’78 but otherwise the frame looks like a 1977. I would rather it were registered as a ’77 but the DVLA inspector looked at the [frame] numbers and said “I recognise this”. Of course, he recognised nothing! He only has the information on his computer!’ So because the frame number relates to 1978, that’s the age-related plate Phillippe received. But he believes the bike’s history may go a little deeper than that…

Because of the mix of different models’ parts, and due to numerous practical tweaks (such as the addition of grease nipples in key places) friends within the scene have suggested that it could be a ‘team’ bike – one which was used by a race team for major events such as the ISDE. Of course, it could simply be an end-of-year mix of parts in much the same way that KTM’s Six Day models used to be a blend of outgoing and incoming model specs. But it’s always nice thinking you’ve got something that little bit special…

List of Ingredients

As desirable as the KTM is, for Phillippe it’s almost just another vintage enduro bike. Over the years he’s has owned, and restored, numerous classics – Betas, Can-Ams, Armstrongs, Bultacos and more – picking models which appealed to him for individual reasons. Perhaps they’ve got the right engine, fine looks, or the fact that he’s simply never owned one. But his real love lays tucked away, stored wrapped in bubble wrap and nestling under blankets…

‘This’ Phillippe states, pointing to a small, half-height wooden shed, ‘is for my wife and boy to use. I felt guilty otherwise’, before opening the door to one of a series of small sheds and workshops and inviting us inside. ‘Switch off your mind and imagine…’, he laughs.

At first glance you notice a BMW 1200GS, the large cylindrical tank of an air compressor, and his well-used 1978 SWM RS-GS 250 racebike. Then you begin to take in the details. There’s the bottom-end of an engine on the lino’d floor, having just had its heavily-finned head removed for rebuilding; a pair of wheels are mounted on one wall; half-a-dozen kickstarts hang on cable-ties from the ceiling; and suspension parts sit propped against walls and shelves. In total there are 14 SWMs here! Plus there’s about to be another one which he’s just acquired that is currently en route…

Yep, the Italian marque SWM (Speedy Working Motors) is where Phillippe’s allegiance lies, and his aim is to have one of each of the now-defunct company’s RS-GS machines. However, he’s not content with simply owning an example of each, because they’re all going to be immaculately restored, something which, we discover, is already well underway.

Whilst we can see numerous bits of bikes, the odd frame and a few forks and shocks, there doesn’t look to be anything like the constituent parts of 14 bikes. ‘You’re wondering where they all are?’ smiles Phillippe, reading our minds. With that he pulls a stepladder from the wall, flicks on a light, and ascends into the rafters. Like a market trader listing his stock, he reels off the parts that are stashed in the roof. ‘There are sets of wheels, suspension, plastics. And all of these tanks have been resprayed.’ He picks up an example swaddled in a blanket with the same care you’d afford a newborn baby and unfurls the material to display his pride ‘n’ joy, shiny red with a bright white stripe and the distinct ‘SWM’ lettering in jet black. Phillippe describes it as ‘my favourite, the nicest of them all’ before placing it on top of a pump-up bike stand. We spend the rest of our time in the workshop tip-toe-ing around hoping we don’t inadvertently send it crashing to the floor…

He then leads us next door to where a small shed is crammed full of parts. There are yet more frames and shock absorbers, and as a perfect illustration of his two passions coming together, French wine boxes crammed full of bubble-wrapped engine cases and assorted other parts, each one labelled with its contents. ‘I’ll spend all of 2012 restoring the parts’, suggests Phillippe. Once that job is done, the bolting back together can commence and then the plan is to have the bikes on display – though it’ll require more space than is currently available – and the conversation turns to moving house. ‘I’ve found myself a nice little place’, he reports, with a wry smile…

Starters, Mains, and Desserts

As we talk Phillippe rattles off models, years, their differences and attributes. His enthusiasm is boundless and makes it abundantly clear that he’s an authority on the marque. So the question has to be asked, why SWM? Unsurprisingly, for the answer we have to look back through Phillippe’s riding history.

‘In 1975 I was 14 and had a Mobylette moped. My first geared bike was a Flandria – a Belgian make – and then a Fantic Caballero. My father owned a garage and I learned how to work on bikes. I fitted the Fantic with a bigger carb, a low pipe and a barrel kit from Simonini which made it all top-end.

‘My first real enduro bike was a KTM 125GS. The bloody clutch was horrible and it wouldn’t start. [Phillippe mimes kicking a bike over, with the accompanying noise of an engine refusing to fire] When you took it out of parc ferme at the start of an enduro you had to take the penalty for it not starting.’

A DT-MX Yamaha wasn’t quite as exotic as the KTM but ‘at least it finished an event’. And then came the epiphany. ‘In 1977 I saw an SWM in a magazine advert for the Milan Show. The bike was designed for the ISDT. I looked at that magazine and thought “one day”.

That day came fairly soon, as Phillippe worked numerous jobs in order to scrape together enough money to buy a secondhand 125GS. Previously the brand had employed Sachs engines which had a reputation for unreliability, though Phillippe’s discovery of the marque coincided with their shift to Rotax motors. ‘The SWM never let me down,’ he reports. The 125 was followed by a 240, after which Phillippe ‘never looked at anything else.’

In 1980 his attentions turned culinary, and Phillippe stopped riding to concentrate on his career. 27 years passed, dirtbike development moved on apace, but when Phillippe got back into enduro (riding H&H and rallies rather than timecards) he plumped for the bikes he knew and began amassing his collection of air-cooled, drum-braked, twin-shocked machines. And what a collection! When they’re all up ‘n’ running, freshly fettled and as good as new, the line-up is going to be a real visual feast for fans of vintage enduro. Because there’s no doubt about it, when it comes to both fine cuisine and SWMs, Phillippe really knows his onions…

As you read this, the 400GS6 may still be for sale. To find out visit Phillippe’s website at www.oldknobblies.com The website has grown somewhat since this feature was first published and is full of a plethora of SWM-related stuff, give it a look… And if you find something you like, tell them you saw this feature in RUST…