Part trials bike, part extreme play bike, part economical trailie, KTM’s new 250R Freeride is hard to pigeonhole. But it’s not hard to fall in love with, as RUST discovered when we travelled to Italy for the world’s first test…

It’s difficult to put a label on the new 250R Freeride. Is it a bike built for extreme enduros, or simply a play bike that’s good at tackling extreme going? Aren’t these two things more or less the same anyway? Even KTM don’t seem quite sure. Their marketing blurb studiously resists the temptation to talk about any kind of competition angle, simply stating that the 250R Freeride is ‘significantly sportier than its 350cc sister model, and even easier to ride in extremely tough terrain’. But then at the press conference they talked about it being the ideal bike for ‘the Romaniacs’, so you make up your own mind.

Tellingly… when we revealed a picture of the new bike on our Facebook page just a day before the press launch, the immediate response from TBM readers was ‘Romaniacs here I come’, and ‘the perfect bike for the Roof of Africa’. Both of which are classified as extreme enduros. Clearly then their customers have their own ideas. Or maybe this is some kind of super-viral marketing campaign on the part of KTM. Don’t plug it for competition at all, simply let your product do the talking for you…

Scene Setting

When the original four-stroke 350 Freeride was first launched back in March 2012, no-one quite new what to make of it. As a pure trailbike it was pretty amazing if you were a beginner, or short in the leg, or if the trail included some trialsey-type going. But for today’s average rider brought up on a diet of high-performance enduro bikes, it was probably a bit too specialist, a bit too spindly and let’s be honest here, a bit too tame for its own good. Sure… every 40-year old trail rider loves a torquey bike, but with only 24hp to play with, there simply wasn’t the wow factor for the average green-laner… Especially if you’d just stepped off a ballsy 450EXC.

KTM quickly realised this and up-specced the motor (via fuelling and ignition timing) to a rather more respectable 28hp and the bike was considerably better for it, but you still couldn’t help feeling that it somehow missed the mark with that de-tuned 350 lump. What it really needed was an engine that gave it instant ‘braaaap’, and the sort of excitement that people craved. What it needed… was a two-stroke motor!

Because, if you get your kicks far from the beaten track, or like to test your mettle on the most ridiculous terrain imaginable, then a two-stroke is still king of the mountain. Last year we asked KTM about the likelihood of there being a 2T version of the Freeride and they suggested that the four-stroke had far wider appeal. ‘Maybe if the concept takes off we’ll see a two-stroke version’ is all they would concede. Well guess what… it did because here it is.

R is (not) for Racing

Named the Freeride 250R, its target market is – apparently – not the racer, nor the ‘occasional’ trail rider, but riders who want something for launching at obscene rocksteps, up vicious ascents and over mammoth fallen boughs, but without the restrictions and limitations of a trials bike. An ‘extreme’ bike, then? Maybe…

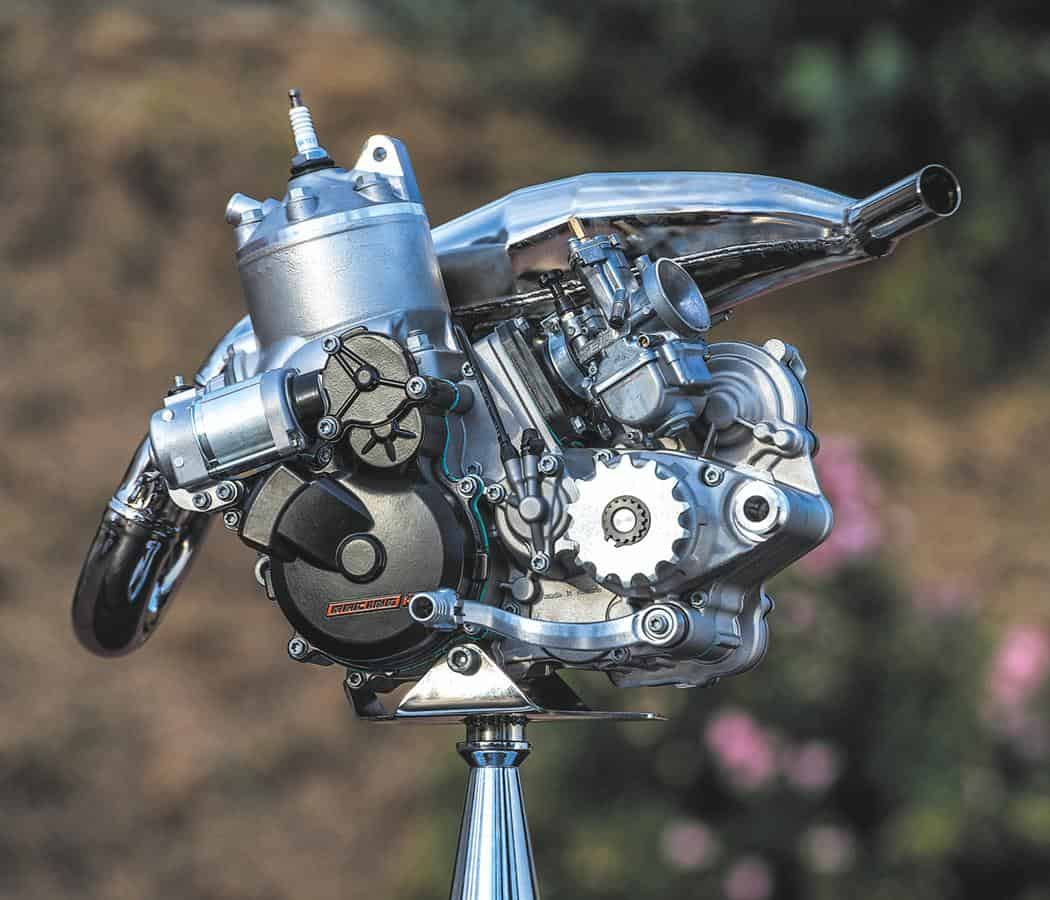

Of course, no-one was expecting the Austrians to simply lift the motor from their enduro bike, change the gearing and whack it into the existing Freeride package, that’s not how Austria operates. And although the engine grew out of the existing 250EXC, it’s been considerably altered to suit this application.

Based on the well proven enduro lump, it’s shed both its kickstart and more crucially its power-valve. Losing the kicker, and therefore the associated shafts and gears, cuts a healthy bit of weight and although there are doubtless times when a kickstart is desirable (having drowned the motor in a river, for instance), KTM reckon it’s one part of the engine you can do without.

The lack of powervalve is altogether more curious, until you remember that trials bikes don’t have ‘em, and the grunt they manage to produce allows them to tackle by far the most extreme terrain of any motorcycle. With a new barrel (complete with different porting), altered timing, plus a revised-to-suit cylinder head, the motor has been tuned for torque, so unlike an enduro bike it doesn’t require a powervalve to help smooth-out the bottom-end in an otherwise relatively top-endy delivery. It simply produces low-down, torquey drive at the expense of ‘on-the-pipe’ wailing power. With an 8500rpm rev ceiling and a claimed maximum output of 25hp it’s more like a trials bike than the typical enduro engine that pumps out high-30s at the rear wheel. KTM admits it took a close look at the porting on modern day trials bikes and built their engine accordingly.

The less aggressive porting is also much kinder on the new piston and rings (power-valves constantly eat away at piston rings) and that means the service intervals of the 250R are greatly increased. We like that. And with new cases and a reworked lightweight waterpump, the 250R’s engine weighs two kilos less than that of the EXC. That’s a decent amount to carve out of a simple 2T lump. We like that too.

The Keihin flatslide carb is significantly smaller than the EXC’s as well, by some eight millimetres in fact (28mm rather than 36mm), and this has quite a profound effect on power, torque and fuel consumption. ‘Markedly below that of the EXC’ is how KTM describe the way the bike slurps its premix, and with a recommended fuel/oil mix of 80:1(!) you’ll be shelling out far less on 2T oil too, plus these bikes are almost smoke-free in use.

The exhaust pipe is curious… it looks like a pet python that’s swallowed the neighbour’s cat. Exiting the cylinder with the traditional enduro curve, it starts off slim – like a four-stroke header or an old-fashioned trials bike pipe – before bulging into a more-or-less straight expansion chamber as it tucks itself out of harm’s way behind the right-hand frame tube… eventually thinning and curving around the rear shock, and exiting on the left-hand-side with a single silencer. It’s not as quiet as the 350’s twin piped system, but it’s not loud either thanks to the relatively low frequencies it produces.

On the 2014 Freerides KTM have ditched their DDS ‘damped’ clutch (as found on the EXCs) and reverted to a more familiar multi-spring device here, claiming that the seven plates, steel basket, and soft springs have been specifically developed for the bike. That’s good, and likewise so is the re-configured six-speed gearbox that has been adapted for the more technical riding the Austrians envisaged for (both) the Freerides, with first through to fifth being lower than usual, and sixth effectively becoming an ‘overdrive’ gear. Sounds very ‘trialsy’, doesn’t it?

Chassis dynamics

Although the ally/steel composite chassis looks almost identical to that of the 350, the two-stroke motor and side-mounted exhaust (as opposed to the 4T’s underslung pipe) have allowed the designers to effectively lift the lower frame rails up by 60mm. A handy 55mm increase in ground clearance is the result (with the seat height remaining the same at a low 915mm) giving an astonishing 380mm of fresh air under the bike – or put another way, almost an inch more ground clearance than an EXC. Don’t tell me that won’t come in handy when log-hopping.

Despite offering better gas mileage than its enduro sibling, KTM have wisely enhanced the Freeride 250’s fuel tank to hold a lot more juice than the 4T 350. The smaller dimensions of the two-stroke lump and the fact that the carb sits a lot lower than the 350’s throttle body meant there was more space available above (and behind) the engine, so they filled it with an extra 1.5L of fuel, giving seven litres in total. Hopefully that’ll be enough to address one of the criticisms of the 350 – its limited tank range.

Something else that’s grown bigger on the 2T is the air filter. The design remains similar – a cylindrical sponge in a clear plastic (pull-out) canister located under the seat – only this one’s got a much taller canister giving a larger filter surface area (almost 50 percent bigger), and looks much less likely to clog than the diddy one on the 350. Owners will like that.

But perhaps the biggest change for the 2014 Freerides concerns the suspension. Both machines utilise the same 43mm USD WP fork legs as before, but the internals have come in for some sensible modification designed to address the shortcomings of the original model.

Originally the bike was conceived as a softly suspended trailie, but owners using the bike at trail speeds quickly found the limits of the suspension. For 2014 KTM have aimed to keep the comfort levels, but get more progression out of the suspension. A new set of heavier and progressively wound fork springs (and heavier shock spring) along with new bump rubbers has eliminated the Freeride’s tendency to bottom out when the going gets rough. And given that the externals haven’t changed, owners of the old model should be able to upgrade their suspension and fit the latest springs.

In keeping with its more serious intentions, the 250R gets slightly firmer settings over the 350 and although travel remains unchanged at 250mm on the forks and 260mm on the shock, both bikes now feel so much better suspended than before.

Before I came to Italy pretty much every Freeride owner I know rang me and asked whether they’d done anything about the Freeride’s woeful brakes? The short answer is yes… though not a lot.

The small master-cylinder remains but internally there are some changes to the ratio of the operating piston, that gives the new Freerides better feel at the lever, and supposedly greater stopping power for less lever effort. This in turn means you don’t have to use the brakes as hard as before and that ensures that less of the heat gets transferred back up through the fluid.

The twin piston, four-pot radially-mounted Formula front brake caliper remains as before though it’s been cosmetically altered with a sandblasted finish on both caliper and reservoir which not only stops ugly chipping but also helps dissipate heat. Meanwhile the hydraulic clutch has been similarly refined to match cosmetically and with new internals to improve the feel.

Ground Control

Another obvious change is a switch away from trials tyres to a whole new breed of tyre developed specifically for this bike. Maxxis have worked closely with KTM to come up with what can best be described as a hybrid trials/enduro hoop, that uses a slightly more open (and taller) block design than traditional trials rubber, but is still visually quite similar to a trials tyre. And best of all it’s made from that ultra-sticky trials compound that feels like bubble-gum.

These tyres feel nothing short of amazing, clinging onto the slipperiest surface with a vice-like grip. If you ride extreme events, ride long distance trials or just fancy testing out the first off-road tyre innovation in 20 years, I urge you to get hold of a set and try them for yourselves (at least the rear hoop anyway). The amount of purchase they have on wet rocks, roots and damp tarmac will just astound you. Be warned though, the front tyre does lack a bit sidewall grip in terms of pointiness for muddy going, but everywhere else they just feel brilliant.

Moving On

For its second year of production, the Freeride 350 has been lightly fettled, with both the engine and chassis receiving modifications – most of which are aimed at increasing strength and reliability.

Inside the motor, the big-end now runs a plain metal bearing instead of a roller part. The SX-F saw the same mod last year, so it’s proved its worth, and the factory are claiming that it extends the service intervals. In the top-end, the exhaust cam and auto decompressor have been given a gentle reworking to provide better starting, and the valve spring retainers have been reinforced. The starter itself has also been beefed-up and the clutch has been changed to the more familiar multi-spring set-up, rather than last year’s diaphragm-spring design. Lastly, a redesigned waterpump cover and associated gasket will help keep the coolant flowing where it should.

Chassis-wise, the suspension is updated in-line with the 250’s units and the wheels are the same Giant rims and machined hubs as found on the quarter-litre bike. Both bikes share the same slimline digital Trail Tech instruments too, which now look much classier than before. It may seem a minor point but it helps add to the feel of quality. Cosmetically, the front fender and headlight surround have been gently reworked, and the bars are now black.

At 915mm the seat height has gained a few mm since last year thanks to the firmer springing, but the Freeride still feels manageable even for riders of limited height, thanks to its low weight and extremely narrow dimensions. However if that sounds too lofty for you because you are – as the Austrians brilliantly put it – ‘of lower tallness’ – then there’s now a Power Parts option of a 25mm lower seat and even a low suspension kit to drop the bike right down again.

Delving further into the accessories catalogue, amongst the guards, the exhausts, the power mode switch and the graphics, are some very interesting items, including a power-up kit which thanks to a less restrictive pipe and an opened up air-filter adds approximately 5+hp to the 350. To further enhance the 350’s BMX-like feel, you can slip-in an auto-clutch and run the rear brake lever on the bars too. Sounds like fun…

The 350 fitted with the KTM Power Parts options is shown below.

Ride Free

But it’s the 250 we were all here in Tuscany in Italy to test out, and using the location for the Hell’s Gate extreme race, we were in for some amazing riding.

Fire up the 250R on the electric starter and it sounds nothing like a modern day two-stroke enduro engine. It’s got that deep bassy note of a two-stroke trialler with the old-fashioned crackle of pre-powervalve Seventies machine as you open it up. Mmmmm glorious.

The other thing you realise within yards of pulling away is that there’s just no point in revving this engine hard at all. I mean you can try but by the time it climbs towards its rev ceiling the torque has all but disappeared and you’re left wondering what happened to the power. Besides with no powervalve, and not much in the way of peak power its rev range is so short, that there’s just no reward in hanging onto the last few rpm.

In fact the ticket to making progress is to short shift through the gearbox at peak torque (kinda 4500-5000rpm) and then keep on selecting gears – up and down. Like a trials bike it’s got a very positive shift between gears (not clunky though), but the gear-lever has been extended a good way forwards, so you have to either use your heel or at least shift your foot forwards on the peg to grab the next gear. Oh and finding neutral is like trying to find free parking in central London. It just doesn’t happen.

I must admit that at first I was riding the 250R all wrong – using lots of revs and working the throttle like you would on a small capacity enduro bike. But eventually I worked out that gear selection is crucial, and low rpm is where this engine does its best work. Once you figure that out (and you do have to re-calibrate your brain to do that), then suddenly the 250R comes alive.

It’s not about power it’s about massive torque and incredible grip and translating that into drive. The combination of that grunty motor and those self-clearing super-sticky tyres is truly intoxicating. I did find myself dancing up and down the gearbox a lot in order to keep the bike in the fat part of its torque curve – not that that’s difficult – but the pay-off is lots of fun and lots of ‘Wow’ moments, on any slope and pretty much every surface.

The test in Italy began in steep woods, before extending out to take in an 80 mile loop of the surrounding trails high up in the Apenine Mountains. The climbs are steep and rocky, littered with boulders and craggy outcrops and then coated in a lovely soft loam. It sounds glorious, and indeed it was, but this going offers the most incredible test of this machine. Climbs that you would really struggle to get up on your EXC purely because of the steepness of the terrain and a lack of grip, the Freeride just romped up them – or in most cases grunted up them. And almost like the feeling you get when riding a trials bike, you start to look differently at gnarly rock slabs and believe that anything is possible.

All the while you’re accompanied by this eery sort of ‘Bwooooooor’ sound, the kind of sound you get when your two-stroke enduro bike is off the pipe and labouring hard in a tall gear. But it’s the sound the 250R makes all the time whether it’s being laboured or revved out. If you remember the pre-powervalve days of the PEs and ITs of this world, then like me you’ll probably find it all rather nostalgic.

Although the 250R’s engine is the centrepiece of this bike, the masterstroke KTM have pulled off is to recalibrate the suspension to allow you to go a lot faster than you could on the old Freeride. This is the real story I reckon, because this is where the lines blur between EXC and Freeride.

Sure for racing you’re still much better off with an enduro bike, but for those riders that like to shoot the trail and keep up a decent pace, the new Freerides now permit you to do that. Instead of worrying about clanging the suspension into the bump stops and what it might do to your spine when it bottomed out, the new bikes are easily able to maintain a good pace no matter how bumpy the track gets. Expert riders will easily outpace you on an enduro bike, but as KTM’s spokesman Jochi Sauer explains ‘this bike gives you the feeling of being ten years younger.’ And he’s right…

And that’s a massive change of direction for the Freerides. All of a sudden these bikes offer a real alternative to the EXCs and EXCFs for the trail, because they are easier to ride, more economical, quieter, lighter and less aggressive.

Okay they don’t offer the same level of stability as an enduro bike – when you have this much manoeuvrability and this much steering lock, plus a shorter wheelbase, you can’t have maximum stability as well – but once you allow for that, and you ride the Freeride accordingly it only catches you out occasionally. Especially if you keep your weight centred or slightly further back than normal.

Because like a trials bike you tend to use more body positioning to boss it around and make it work for you, and because the wheelbase is shorter you need to hang back a lot more over the rear fender on steep descents, but actually that’s all part of the fun of Freeriding!

And perhaps the place where this was best demonstrated was on the long rocky downhills with big steps, where on the old bike you would have been forced to take it slowly, now thanks to firmer suspension and a sportier ride you can launch the bike off the rock steps safe in the knowledge that the front won’t bottom out and tuck as you land.

Not surprisingly it reminds me a lot of the final version of the old Gas Gas Pampera. Better styled, much better built and with better suspension of course, but dynamically a very similar concept. Like the Pampera the Freeride 250R is not the fastest of machines but its capabilities are pretty astounding and seriously addictive…

Good Thumping

I must confess I wasn’t looking forward to riding the new 350 Freeride – we’ve had a long-termer all year so I know exactly what it feels like and the 250R promised something new and different.

So it was a real revelation when I climbed on board and found myself liking it immediately. The new suspension has to take all the credit because in place of the sloppy and bouncy old feel there’s suddenly an extremely well-damped and well set-up trail machine.

It rides far better than before too – waaaay better. The new suspension isolates the bumps better than before, allowing you to ride faster without fear of the bike getting out of shape. You don’t immediately notice the extra eight kilos the 350 weighs over the 250, but what you do notice is that the thumper follows the contours of the ground much closer. Where the 250 allows you to be creative with your line picking up the front wheel a lot more, the four-stroke simply sits on the lowest point of the trail and trundles along.

But I was staggered at how good it felt on the rocks too. Part of this might well be down to the new tyres, part of it is the suspension, partly it’s the new lower internal gear ratios, but collectively it all adds up to a bike which is far more at home in this sort of going. And good though the old bike was, this one is a considerable improvement.

Rock steps are dispensed with ease… slippery rooty climbs it just flows up them, and though you don’t have quite the same choice of line as you do on the 250R, neither do you get deflected off course quite so easily either. So this bike feels the more stable of the two, and being quieter and less raucous it’s definitely more civilised as well.

When I was feeling tired just before lunchtime, I switched to the thumper and was pleasantly surprised at how easy it felt to ride after the 250R. Whereas the 250 is all point and squirt, the 350 flows over the landscape much more serenely. You barely notice the difference in ground clearance (I scraped the underside, just once all day), but you do notice how swiftly it covers the ground now.

It still feels slightly lacking in power compared with an enduro bike (especially a 350EXC), but the fluidity of its ground covering plus the fact that it could hold onto gears for longer than the 250R, actually made it easier to ride fast than the 250.

Sadly one area where I can’t report real progress is with the brakes. Or the front brake at least. You still have to give the lever a good strong pull to haul the bike up and the brake just doesn’t have the initial bite of a good Brembo set up. It’s okay, but it’s not as good as I’d hoped. In fact I found myself using the rear brake a lot more, and because these bikes transition the gap between trials bikes and enduro machines, you tend to ride the bikes a bit more ‘rear-endy’, keeping your bum as far back as you can during braking and really scrubbing speed with the rear. But for those that want even more rear brake, I’m told that the larger rear disc off the impending electric Freeride E is available as an option, and that’s probably worth exploring.

What Gives

So KTM have evolved the Freeride concept, making it more trialsey, but at the same time making it a much better prospect on the trail. Both bikes are different and both will have their followers. The 350 is far more capable than it was before, yet somehow still remaining civilised and easy-going.

The 250R is the snake in the grass, it’s lively, raucous and quite bonkers at times, but it brings a whole new dimension to fun trail riding. I guess if you live somewhere where the going is fast and open it’s not going to have any effect on your life at all. But if you live somewhere steep and hilly, and like the idea of a low-impact trailbike but still with sporting and trialsey pretensions, then the 250R will open up a whole new world of riding to you.

It’s amazingly fun, and one of those machines that can genuinely lay claim to bridging the gap between beginners and experts alike. And unlike a pure trials bike it offers the potential to cover some ground in comfort and at speed. I loved the 250R, and I can see a lot of potential for it in the UK and elsewhere. The long distance trials riders are going to snap them up, but I reckon other trail riders might just look at themselves and consider why they’ve been rushing headlong down trails on their EXCs missing out on the scenery. Instead they might like to consider pulling on an open-face lid, knocking 10mph off their speed and broadening their smiles because the 250R is the sort of bike that makes you smile every time you ride it…

KTM Freeride 250R (350 in brackets)

Price: £5995 (At time of publishing)

Engine: Reed-valve, e-start, 2T (DOHC, fuel injected, 4T)

Displacement: 249cc (349cc)

Bore & stroke: 66.4 x 72mm (88 x 57.5mm)

Gearbox: 6-speed

Frame: Perimeter steel/aluminium composite, polymer subframe

Front susp: WP 43mm USD fork, fully adj

Rear susp: WP PDS shock, fully adj

Front brake: Formula four-piston radial-mount caliper, 360mm disc

Seat height: 915mm

Ground clearance: 380mm (325mm)

Fuel capacity: 7L (5.5L)

Weight: 92.5kg (99.5kg) claimed

Contact: KTM UK on 01280 709500 www.ktm.com

Evolution of the Species

As is so often the case, it takes the involvement of a major manufacturer to really ‘launch’ a new class of motorcycle. Until then, innovative bikes are often regarded as niche market machines and the trail/trials crossover concept is a case in point. Because the Freeride certainly isn’t the first of this style of dirtbike, not by a long way…

Really that accolade should go to Gas Gas, with their Pampera. It’s now 18 years since the first Pamp left the Spanish factory with a two-stroke trials engine snugly ensconced within a lightweight trail bike chassis. In the model’s ten-year history (the last was built in 2005), the bike underwent gentle refinement – the mkI being very trialsy especially in its gear ratios, and the mkII much more civilised on the lanes but much cheaper built – culminating in the most trail-friendly of all, the mkIII. Although the last generation Pampera was built to a budget (soft rims, naff chain etc) and STILL suffered from a trials-derived gearbox, it did combine an amazingly nimble and lightweight, yet trailable, chassis with the go-anywhere power delivery of a trialler.

Subsequently, a number of trials manufacturers have offered bigger tanks and padded seats to bolt onto their trials bikes in order to endow them with some semblance of long-range rideability, and in 2008 Beta reversed the trials engine/trail chassis theory and gave owners the option of stripping the tank cover and seat from the latest Alp 200 to give the air-cooled trailie’s chassis a more trialsy feel.

However, it was Scorpa who were the first factory to follow the line drawn by the Pamp and ‘08 saw the French brand produce an agile, compact, trailie using trials ‘motorvation’. Okay, so the engine in question was actually Yamaha’s WR250F lump, but that was what they were running in their four-stroke trials bike at the time!

Known as the T-Ride, the Scorpa was heavier and revvier than the 2T Gas Gas, and whilst it was incredibly easy to throw about, much of its easy-going nature was due to the fact that it simply didn’t make that much oomph. This made negotiating wet slabs a doddle, but it ran out of mumbo on big climbs.

A little dealer-derestriction helped to free some more power, and by using a well-proven four-stroke engine the T-Ride was more civilised and versatile than the Gasser. Still, a retuned enduro motor was never going to match the old Pamp for cliff-scaling grunt…

No, that bike would arrive at the end of 2011, when Ossa unveiled their innovative, reverse-head, fuel injected, two-stroke Explorer – a thoroughly modern take on the Pampera theme. By this point interest in trials/trail hybrids had grown exponentially, as it was around then that KTM announced that they’d be building the Freeride 350, and both Scorpa and Sherco revealed compact trail bikes running trials-derived engines.

The influence of extreme enduros seeped into our riding and the changing face of dirtbiking (trying to get the most from what little land we can still use, or easily exploring terrain that was previously inaccessible on conventional machinery) brought new life to a class that could so easily have fizzled-out years ago…