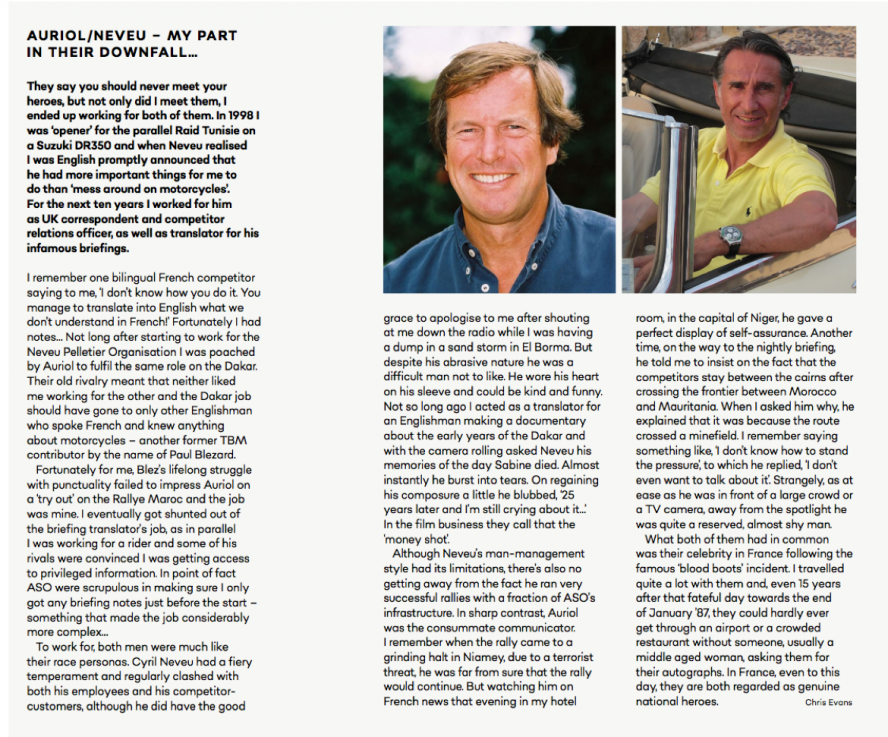

story by Chris Evans

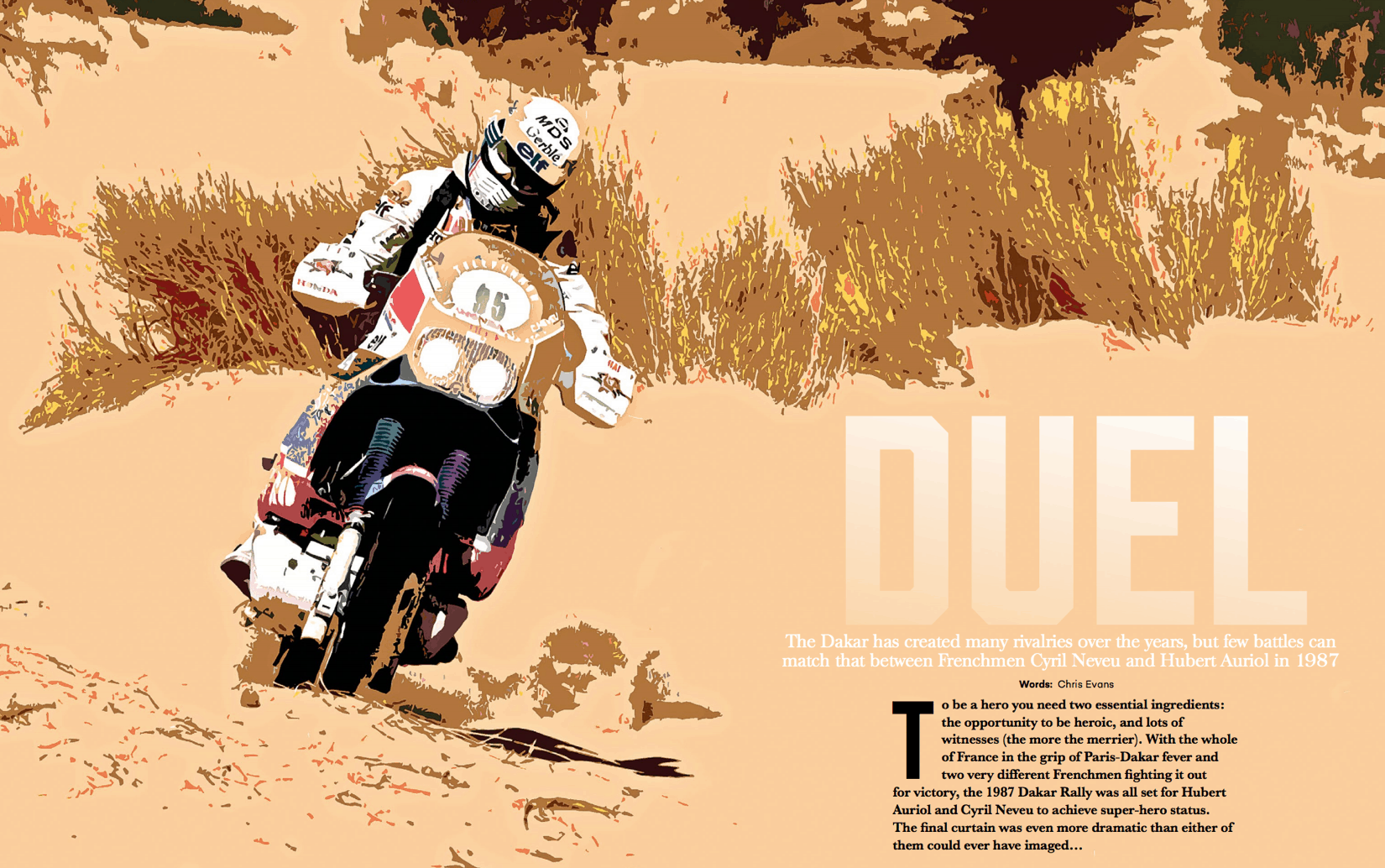

To be a hero you need two essential ingredients: the opportunity to be heroic, and lots of witnesses (the more the merrier). With the whole of France in the grip of Paris-Dakar fever and two very different Frenchmen fighting it out for victory, the 1987 Dakar Rally was all set for Hubert Auriol and Cyril Neveu to achieve super-hero status. The final curtain was even more dramatic than either of them could ever have imaged…

THE MEDIA MONSTER…

There’s no denying that the Dakar gets the sort of media coverage that other off-road events can only dream about. This year it was broadcast in almost 190 countries, with 70 channels putting out a staggering 1200 hours of programme time. While globally the race’s popularity increases year on year, paradoxically in France, from where it is organised, it no longer enjoys the almost saturation coverage it attracted in the politically incorrect 1980s. Back then, in the era of big shoulder pads and suitcase sized mobile phones, the Paris Dakar was a media monster. The two big glossy weekly mags Paris Match and VSD were main sponsors, as was the radio station Europe 1 and national TV. Across the country families who had absolutely no interest in motorsport sat down nightly to watch their heroes battle it out on the pistes of Africa. It was like the Tour de France and Wimbledon all rolled into one. Its almost instant success had a lot to do with the visionary genius behind it, Thierry Sabine, who was also the brains behind the most spectated off-road event in the world, the Enduro du Touquet. He actually pinched the rally-raid idea off a bloke called Claude Bertrand, who organised a race called the Abidjan-Nice. Sabine signed up to the second Abidjan-Nice at the tender age of 27 and while lost in the Sahara for three days vowed that if he survived he would organise something even more insane. The Paris-Dakar was born.

AN IRRESPONSIBLE DREAMER

A charismatic chap, who some considered an irresponsible dreamer, Sabine captured the French public’s imagination by sending his competitors across the desert with precious little in the way of logistical support. Incredibly, participants had to sort out their own catering arrangements, if your vehicle broke down it stayed where it was and with no distress beacons getting lost was best avoided. To even consider entering the race you had to be a little insane and to win it you had to have levels of determination that few mortals possess. Being fast on a motorcycle was not necessarily a prerequisite for success. Having nerves of steel and highly developed sense of orientation were most certainly were. Step forward our two heroes du jour, Monsieur Auriol and Monsieur Neveu. Prior to entering the Dakar both were competing in motorcycle sport but neither were massively successful. But as it turned out, both had what it took to nurse a slow and ill-handling motorcycle, loaded down with fuel and spares across a very large desert. What makes theirs such a great story is that it’s about all they had in common. Hubert Auriol was tall, good looking, educated and born into the upper echelons of French society. Rumour had it that he was related to another illustrious Frenchman, a certain General Charles De Gaulle. Raised in Ethiopia and a fluent English speaker, he was nicknamed Le Bel Hubert and had an easy charm that women and sponsors loved. Cyril Neveu had none of Auriol’s social graces. Small, aggressive and from humble origins he was legendary for torturing the French language and spoke absolutely no English at all.

THE RUNT OF THE LITTER

That didn’t stop the runt of the litter winning the very first Dakar in 1979, aboard a privately entered Yamaha XT500. Auriol, also XT500 mounted, finished 12th overall and 7th motorcycle home – in those days there was no separate classifications for bike and cars. Convinced he’d have a better chance of winning on something more powerful, Auriol was back in 1980 aboard a BWM flat twin but was disqualified for some ungentlemanly cheating, leaving his nemesis Neveu to win again on his XT. Auriol got his revenge in 1981, getting his big Beemer across the line in first place, while Neveu, having switched to Honda, could only manage 25th place on his XLS500. Neveu was back to his winning ways in ‘82, while Auriol, along with all the other, by now factory, BMWs went out with gearbox problems. 1983 saw Hubert win his second Dakar, while in ‘84 he finished second to someone who made Neveu look tall – the diminutive Belgian, Gaston Rahier. For 1985 Auriol followed the money with a switch to Cagiva/Ducati for a rumoured US$1million! Italian reliability problems meant that he was unable to supplement his basic salary with any win bonus for the next couple of years, allowing Neveu to take victory in ‘86 on the now legendary Honda NXR twin.

But what made the headlines in 1986 wasn’t Cyril’s win but the death of organiser Sabine in an early evening helicopter accident, while out looking for lost competitors. With his smoke flares and white jump suit, Sabine enjoyed rock star status in his country of birth and even today people can still tell you exactly what they were doing when they heard of his death. Human nature and the media being what they are, the 1987 edition, run by Sabine’s dad Gilbert, was even more eagerly awaited and more closely followed in France than previous editions. Neveu was again on HRC’s massively accomplished V-twin, while Ducati had finally got their act together and given Auriol a bike he could win with. The stage was set for the mother of all battles.

THE MOTHER OF ALL BATTLES

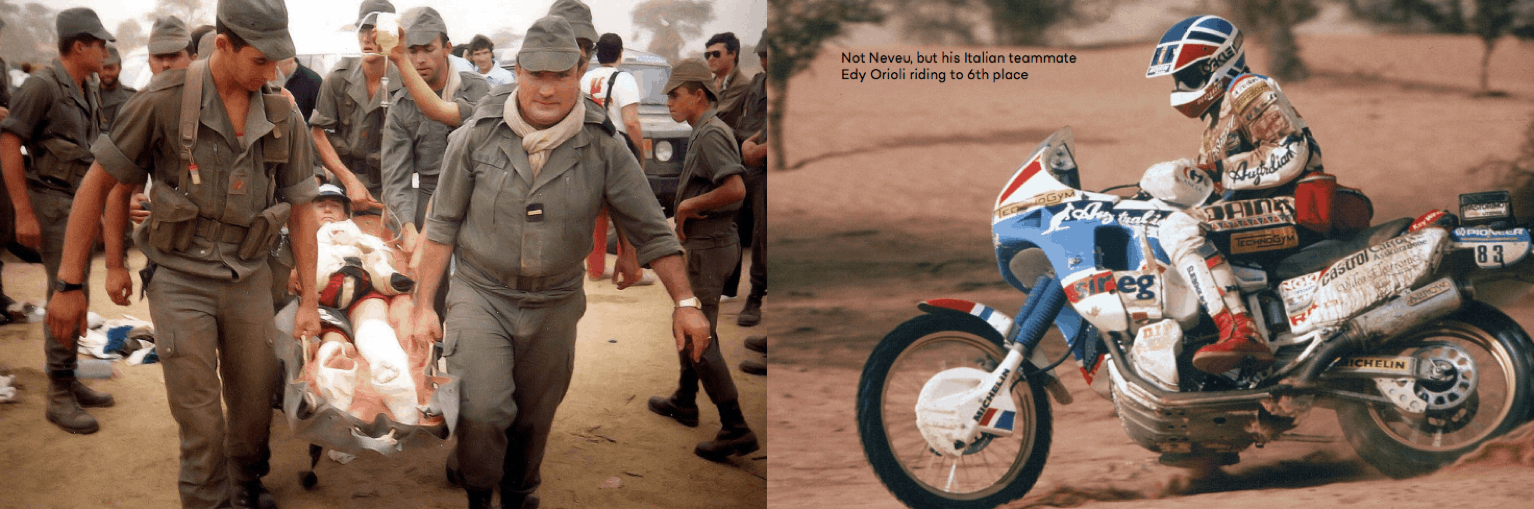

Throughout much of the rally the two men swapped places at the top of the leaderboard and with the rally running for 21 days at that time the psychological pressure the two men had to withstand was almost unbearable. But following a series of navigation errors by Neveu, as they approached Lac Rose, on the second to last stage, Auriol started the day with an almost comfortable 12 minute lead. As determined as ever, never-say-die Neveu attacked the stage relentlessly and crossing the finish line first, kept one eye on the stopwatch and the other on the horizon, in the slim hope of having reduced the lead enough to be able to take the win on the next day’s, last short stage. As other riders arrived at the finish Neveu and the media scavenged for news of Auriol and it soon became apparent that he had run into difficulties, with one rider claiming to have stopped to help him get back on his bike after a crash. Finally, Auriol rode into view and a by now almost beside himself Neveu, realising that he was still three minutes down, began to accept defeat.

Until that is, with cameras rolling, Auriol cried out, ‘I’ve the two ankles…. I’ve the two ankles broken’. The doctors present at the scene cut off his boots and indeed they were, one with an open fracture! Tears streaming down his dirt streaked face and rolling around in agony on the ground, Auriol cried out, ‘Cyril is too strong!’ and promptly announced his retirement from bike racing. If there has ever been a more dramatic end to a rally I’m not aware of it and watching the YouTube footage on the ‘net 29 years later, the scene has lost none of its impact. Best of enemies, they went on to write a bestseller of their battle titled ‘Une histoire d’hommes’. True to his word Auriol never raced a bike again but became the first man to win the Dakar on both a bike and in a car. Neveu’s 1987 victory would be his last. Both eventually switched to organising rallies with considerable success. Auriol would run the Dakar for nine years on behalf of ASO while Neveu would take over the ailing Rallye Tunisie and turn it into a very profitable enterprise.