2009: This is the Steve McQueen Metisse Desert Racer. Hand made in Oxfordshire. To you sire, a shade under £14,000. But forget the name, forget the ticket price – the Desert Racer is about something more profound

There’s no question, this is a beautiful moment in time. It’s mid-April and spring has finally sprung in England. We’re sat next to the 18th green on a fine golf course in Oxfordshire, basking under a warming sun for the first time in months. Incredibly just minutes ago, and barely ten feet from us, a Kestrel had plummeted from the sky and plucked a vole from the long grass (‘the rough’, as the golfers call it). We could have reached out and touched the bird as it tucked its prey in its talons and took off for a nearby oak, to sit and pick over its afternoon tea.

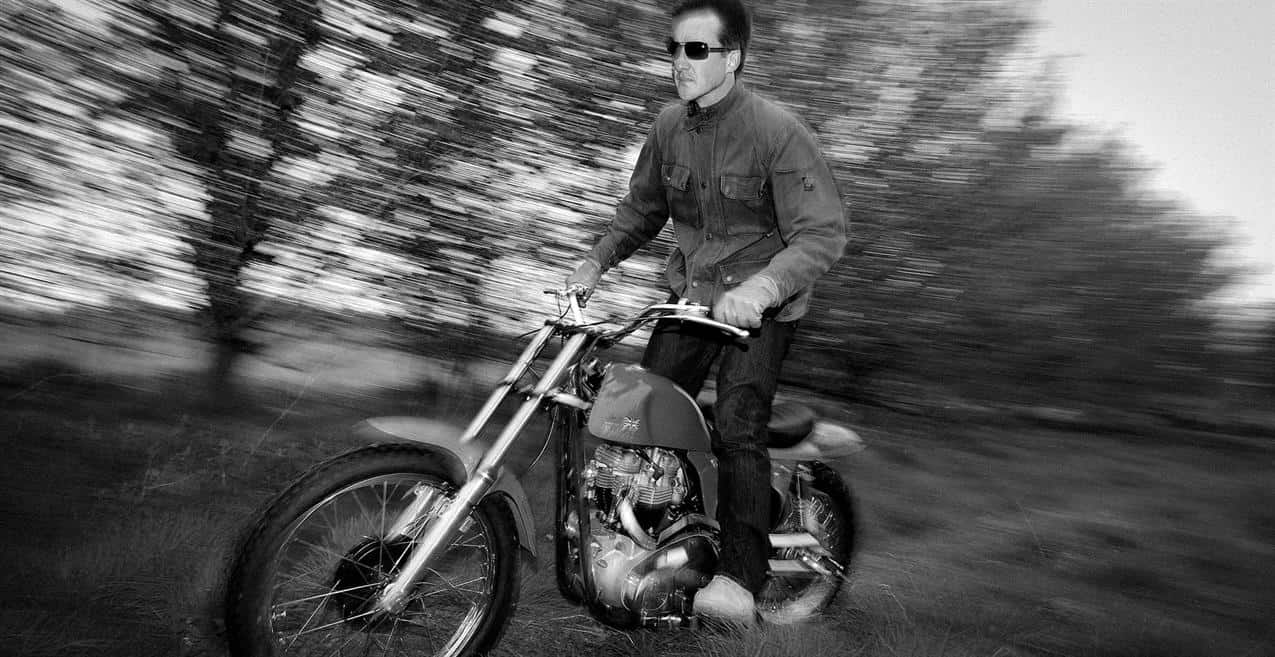

But the beautiful moment has nothing to do with the golf course or the bird of prey. It’s because we’re poised to fire up, for the first time, a brand new Metisse-Triumph scrambler, or rather a Steve McQueen Metisse Desert Racer to be more accurate. It would be judged a machine of beauty in any age. Shapely – like a woman, opines our photographer – yet masculine at the same time. The 650cc TR6 unit is a big beast of a motor for an off-roader, even today.

There’s no key, no electric starter to this bike. The only electrical control is a kill-button on the left handlebar. Instead the start procedure is entirely of the analogue era. You reach under the fuel tank and pull out the brass pull-push petrol cock, then place your thumb over the ‘tickler’ on the single Amal Monobloc carburetor and hold down until fuel pours over the float bowl. There’s no choke and there’s no advance-retard either (that you often find on older Brit bikes). It’s just a matter of folding out the kick starter, turning the motor over until there’s some resistance (compression) and then offering a solid swing of your boot. First kick illicits a rumble, second kick a hearty roar. The motor dies immediately, though. Two or more kicks and the Metisse at last stays lit. Unsilenced, the exhaust note is glorious, actually not that loud, but of a suitably guttural descant, producing a fine ‘roooooooooombaaaaa‘ – and you really get to like the ‘baaaa’ of the over-run. And actually it revs up rather quickly, we’d maybe expected it to be lazier, the product of a heavy crank, but no, it’s pretty free-revving, pretty urgent as it goes. There are, needless to say, broad smiles all around – even among the golfers.

McQueen’s bike?

I’m wondering, as the Desert Racer warms, is this bike not, technically, the second Steve McQueen replica on the market today? The first being, of course, Triumph’s Scrambler. Now the Scrambler doesn’t actually have McQueen’s signature on it (neither is it endorsed by McQueen’s estate), but it is a replica of sorts (or rather a pastiche) of the TR6 Trophy model made by Triumph from the mid-1950s onwards. That was the bike that made The Big Leap in The Great Escape (with desert racer come stuntman Bud Ekins in the saddle). And the TR6 Trophy in ‘SC’ guise was the model that McQueen famously also rode in the 1964 ISDT. Curiously, for 2009, Triumph do now offer the Scrambler in a military (Wehrmacht?) green – arguably making it a true TGE replica. Alternatively you can still buy one in the two-tone style of the sixties and add Triumph’s ISDT-styled accessory number boards which, in the brochure at least, feature McQueen’s riding number in that ISDT – 278.

But to be fair, the Scrambler is a modern motorcycle, featuring a modern 865cc fuel-injected motor in a modern chassis. It teases at the McQueen legend but that’s the beginning and end of it.

This Desert Racer, though, is the real deal. Metisse’s owner, Gerry Lisi, has researched the matter thoroughly, working alongside McQueen’s son, Chad, to ensure absolute authenticity. McQueen unquestionably owned, raced and appeared in film with TR6s and TR6SCs, but the Rickman-Metisse framed Triumph (of which this is a replica) was a bike he built and raced for himself through 1966 and ’67. It’s also the bike on which McQueen appears on the November 1966 cover of Popular Science – an American science and technology magazine. McQueen wrote a brief test on his desert racer for that issue and reported, “This rig is the best handling bike I’ve ever owned.” So while the TR6SC is the bike we so often associate McQueen with (well, that and the 1970 Husqvarna 400 Cross he rode in On Any Sunday), unquestionably this desert racer was as personal to him as any bike ever became.

Yet sitting on the bike in Oxfordshire, as ever, I remain a little perplexed. For while Steve McQueen is the name on the tank, who is to some degree the designer of this bike and is the very reason for this bike’s existence, the story behind this replica involves so many other people’s lives. Like Gerry Lisi – whose father was a real WWII Prisoner of War (an Italian interred in England) – who rode scrambles in his youth and fell in love with the sleek Rickman Metisse framed racers way back then. Like Don and Derek Rickman the talented scrambling brothers (and Motocross des Nations winners) who created the Metisse frame, making some 20,000 of them in 20 years. It was Derek, on McQueen’s request, who sourced the distinctive grey (battleship grey, in fact) paint of the original McQueen desert racer. And like the late Pat French, who took over Metisse in the 1980s, whose impeccable workmanship inspired Lisi to buy a share of and eventually the whole company.

McQueen may have ordered the frame, then one summer in 1966 (at the bike shop he co-owned with Dave and Bud Ekins) assembled the original bike, but today’s Desert Racer has its step-fathers too.

Desert racers?

Sat on the golf course, we were of course thousands of miles from any desert. And it takes some thinking, and some research, to figure out just how this bike is a desert racer, as against a normal dirt bike – and exactly what the attributes of a desert racer are.

Desert racers back in the 1960s were an American thing, more particularly a Californian thing. One hour out from Los Angeles and literally all around Las Vegas is the Mojave Desert. It straddles the state and even creeps into Nevada and Arizona. And if you head due south, desert continues out on to the Baja peninsula too. It’s one big old ‘nothin’. And for motorbikes it’s one natural born playground. It’s worth adding that a lot of it is also flat and while occasionally bumpy it’s not all whooped-out the way motocross tracks and even enduro trails get today. And it’s a little known fact that the Baja 500/1000 desert race in its original format was for some 25% of its length a surfaced road. Another good portion was classified as fire road (like a gravel road) and even after those you can feature in dry lake beds too.

So you can see long travel suspension wasn’t necessarily high on the list of requirements for a desert racer. Nor necessarily was light weight. But a motor that could go long distances, haulin’ say a good 100mph or so – now that’s a useful tool. And that was in essence the 650cc TR6 motor. Designed by the British engineers specifically for the American market, it was capable of 100mph right from the get-go in 1949. The aforementioned TR6SC was a later limited edition – detuned – version and while some have thought the SC stood for ‘special competition’ it’s just as likely to stand for single carb, for that’s a key identifier. The SC ‘desert sled’ was built for reliability as much as performance. That 100mph potential came at some sacrifice mind, for while the slower TR5 500cc twin favoured in European enduro competition made for a machine weighing in at around 114kg (260lb), the TR6 was a proverbial tank of 147kg (325lb). But in the desert the power, and speed, advantages of the 650 outweighed, quite literally, its increased bulk.

It should also be said at this juncture that desert racing was big business. Southern California had up to 20,000 licenced desert racers at any one time, nearly all amateurs. The famous Barstow to Vegas race at its peak in 1971 attracted 3000 racers – and tough race that it was, only 615 finished. You can but imagine the size of the sweep crew.

Against this backdrop, for two decades (through the 1950s and ‘60s) the TR6 and derivatives therefrom, like the Rickman Metisse, were the desert racers to have. To coin the Americanism, it was the winningest bike in desert racing history. And needless to say ex-Marine Steve McQueen rode one.

And given the size of the market it’s no surprise the Rickman brothers, obviously savvy marketeers, took their Triumph-engined Metisse (mongrel, in French) racer to the Californian desert races. Winning desert races, as they did, certainly helped the canny Brits to export units. And so it was that the Ekins brothers, Dave and Bud – both highly respected desert racers and bike dealers – were importers of the Metisse frame kits. And it’s through them that their business partner McQueen acquired his frame.

The Metisse was quite an upgrade from a stock TR6 too. While McQueen in his magazine article would revel in the technological breakthrough that (apparently) was the oil-in-the-frame feature – aiding cooling and so reliability – it’s fair to say he would have equally appreciated the integrity of the altogether more purposeful frame (fabricated in Reynolds 531 tubing) and the near 30kg (60lb) weight saving the conversion allowed over the donor machine.

Neat ride

Riding the Desert Racer then, is to open a window into the world of 1960s Californian bike culture. McQueen’s personal preferences – whether deliberate or accidental – are all replicated on this bike. Immediately you are impressed by the rearward sweep of the ‘western-style’ handlebars of the era, mounted on BSA yokes (McQueen pronounced them the strongest he knew). Combined with quite forward placed (fixed) footrests, there’s no question this is a dirt bike you operate seated. All of us today have learnt to ride the dirt standing, so it’s an unbelievably alien setup. Your backside is virtually over the rear wheel spindle – these days we’re chasing the front axle instead. That said, in essence it’s a comfortable position – just watch for the bumps.

The gear change and rear brake levers are of course reversed to today’s norm. But snick the Metisse in gear (with a firm right foot) and let out the relatively stiff clutch and the beast storms away. Which is a cue for your already mile-wide smile to reach both ears. The exhaust bark is one of authority and even though this motor was brand new there was a keen sense of willing.

I’m dubious as to whether on the gearing provided that it will reach the ton, but the Desert Racer will obviously fair haul. So it’s just as well it would be doing this in the vast reaches of the desert, for stopping is not the Metisse’s strong point. The front brake, probably because it was brand new and not yet bedded-in did virtually nothing to slow the bike. Lisi suspects the Triumph hub (in this case a replica that Metisse cast and machine themselves) that McQueen chose to fit might have been nothing more than an available wheel left lying in the workshop with no better job to do. Back in 1966 there were plenty of stronger alternatives.

By comparison the BSA rear hub (again today fabricated by Metisse) has more stopping power than you could ever need. You kind of suspect that while today we are very much front end biased, it was the opposite back then. Perhaps that’s why, too, desert racers typically chose to run trials pattern front tyres (typically the Dunlop Trials Universal) with nobbly rears. Today this combination gives us the heebee-geebees, but that was the hot set-up back in the day. As were 19” front wheels – until the Rickman brothers won on the 21” front shod Metisses.

So let it be said, from a test ride perspective this report will fail, we’re not testing it in a desert but curiously on a golf course. And like I’ve said, today when we’re riding we’re standing, elbows up, head over the bars, knees slightly bent. Making the transition back to 1960s technique was simply too much to fully assimilate and it took Lisi to demonstrate exactly how to really ride the Metisse. Relaxed, seated (obviously) and working great handfuls of throttle, Lisi circulated our test field – the golf club’s driving range, would you believe – at great speed. His cornering speed was truly impressive – we were concerned that fixed foot peg would dig in at any moment – as was his ability to pour on the coals mid-turn and get the Metisse drifting – he’s done a bit of grass track has Lisi. If we were impressed with the Metisse before, Lisi’s demonstration had us won over.

It is something of a tragedy then, as Lisi confirmed, that of the 25 or so Desert Racers already sold almost all were purchased as trophies, probably to stand silent in some millionaire’s games room and most are unlikely to ever be started, let alone ridden.

So what do we learn?

Sometimes it’s handy to step backwards to see where we’ve come from, to measure our progress. It would be easy to judge the Desert Racer as an old nail from yesteryear, long past its sell-by date. But it’s not. Honestly, the guys at Aprilia should have made a study of the TR6 powerplant and its power delivery before they set out on their 4.5/5.5 vee-twin project. There’s something to be said for power that comes in early and authoritatively, that finds traction and offers the rider a real sense of control. And have a think about the Metisse’s weight: 136kg. This, for a 650cc twin – that’s only 9kg heavier than Suzuki’s DR-Z400! Okay, thankfully today top four-stroke motocrossers are coming in under the 100kg mark, but there are an awful lot of enduro and trail bikes out there claiming to be svelte that clearly aren’t – like Honda’s CRF450X at 122kg (claimed). And while I can’t honestly say I’m ready to step backwards to riding on 7” and 5” of suspension movement (front/back) there is an argument that long travel suspension has done little for us other than generate bigger bumps. Did the term ‘whoops’ even exist before the mid 1970s?

The fact is that sometimes we look at these old bikes and scoff. We shouldn’t. The fathers of today’s Californian dirt bikers were happy to hang off these machines at anything up to 100mph on the gravel. Quite a few died doing it. Today we don’t have any 100mph dirt bikes (we know of) and we plan our courses to typically run quite a lot slower. And we have to acknowledge, without a show of a doubt, that guys like the Rickman brothers made giant leaps toward the future we now enjoy. We ride what we ride today because of bikes like the Metisse. This bike may have a stamp of Hollywood, but its roots are are firmly in New Milton, Hampshire.

Reflections

We actually rode around on the Metisse for far longer than we anticipated. Lisi had suggested ours would be but a quick taster, but once fired up the Metisse (again) melted his heart as much as it did ours. And it would melt the hearts of those eternal wags on the internet, who in this case have called in the McQueen linkage as nothing more than a marketing trick. It’s not and while we too were a touch sceptical at the outset, now we have nothing but admiration for what Lisi’s doing here. And dare we say that at just under £14,000 the Desert Racer is in all actuality good value for money. For the money, Lisi’s Metisse factory not only makes the frame, they fabricate the hubs, the Ceriani-replica forks, the yokes, the fibreglass bodywork (the list goes on). They then complete refurbish American-sourced used TR6 motors (to indistinguishable from new) and build up the whole project so it’s ready to ride. And having ridden the bike – and seen Lisi properly ride it – we can confirm that it really does ride very well, certainly just as McQueen would have recognised.

Which leaves just one observation. There’s this curious almost-link buzzing around my head. When interviewed in Popular Science on why he loved desert racing, McQueen answered, “It’s the clean smell of the desert in the morning.” Now McQueen had been pencilled-in to play the role of Colonel Walter E Kurtz in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now, but it would seem his ill health (he died of cancer in 1980) prevented him taking the part. In that film Marlon Brando instead played Kurtz. The same Brando who rode a TR6 Thunderbird to notoriety in The Wild One. But – and here’s the agonising almost-connection – it was Robert Duval, as Lieutenant Colonel Bill Killgore who said, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning… smells like victory.”

One Response

I first drove a Rickman Metisse in 1971. A friend at a Gainesville Triumph shop, Listen Chapel, a flat track racer, insisted I try his bike after learning my first bike was 1966 TRC “Jack Pine”. My TR 6 was in the shop for some handlebar change. The Rickman bike easily pulled the front wheel up in any of the first three gears. Sadly Listen was paralyzed in a race and when I visited him in the hospital he was so depressed that it didn’t come as a shock when I later learned of his taking his own life. I am 76 years old now and still ride (R9T Scrambler) but I keep a large poster and photo of him on his race TR in my garage. Always take a moment to remember riders who have passed on. J. Parker Clermont, FL