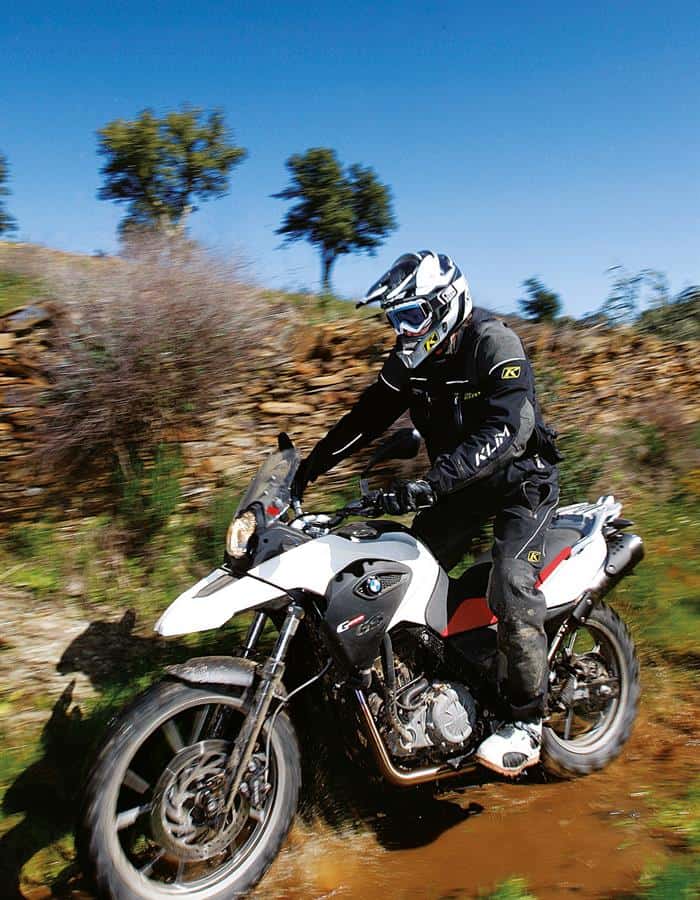

Rising from the ashes of BMW’s single cylinder F650GS comes this – the new G650GS. A worthy successor to the popular dual sporter? We found out on the trails of northern Portugal…

Jack of all trades, master of none: an oft-used phrase that pretty much sums up the dual sport market. We want a bike that’ll cope with hundreds of road miles, yet will still whisk us down a green lane without tying itself it knots, getting stuck in the first muddy puddle, or firing its rider over a dry stone wall every time it meets a bump. And we also demand longevity and practicality. Oh, and of course, if it’s inexpensive to buy and cheap to run then that’d be quite nice too.

BMW’s single-cylindered F650GS (and its ‘dirtier’ Dakar variant) was that bike. It wasn’t flash, but it simply did everything you asked of it (within reason!). Then the factory killed it off and replaced it with their G650X models…

Unfortunately the Rotax-motored G650X range didn’t really hit the spot with the bike-buying public. Perhaps someone in Munich thought that by splitting out the greenlane, backroad and commuter abilities of the old F650GS and producing three more focussed models they’d shift a few more units. Sadly, it wasn’t quite the success they’d hoped for…

The Xchallenge was a very competent big-bore trailie, but just a bit too hard edged for the dual sport market. And at the same time it was far too big and unwieldy for the competition boys. The Xmoto supermoto was a fumbled first-gear power wheelie in a world of through the ‘box monos, and the Xcountry, well, it was a commuter bike that wanted to be a trailie. And I’ve never seen one in central London nor on the trails…

In 2009, just two years after their launch, the G650X models were dropped from the line-up and that, we thought, was the last we’d see of single-cylinder Rotax-engined Beemers. But no! Because much to everyone’s surprise, they’ve brought back the old F650. Except they’ve since used that moniker elsewhere (on the 800cc parallel twin), so this time it’s called the G650GS.

Of course, the G-GS isn’t simply a new name on an old bike, it’s more of a new name AND a new set of clothes on an old bike – the steel frame and Rotax engine are the same as on the old F-GS. Though actually that’s not such a bad thing. Because there was quite a lot to like about the old F650 single. Oh sure, knocking on the door of 200-kilos meant it had a power-to-weight ratio akin to that of a small office block. And the motor was a touch vibey. AND the gearchange was clunky. And…

Well despite all that it had a real feeling of solidity about it. The F650 was the kind of bike you could ride to a UK rally, flog around a forest all day, and then ride home again. I know because I did it. There was nothing sexy about the bike, but it was damn near bulletproof. And that’s a very appealing quality in a bike, whether you’re heading off around the globe, a novice rider, or just strapped for cash. Or maybe all three.

G-String

Sleeping out under canvas in March is rarely an enjoyable experience but that’s just what BMW had in-store for us on the G-GS launch, followed by a full day out on the trails. Thankfully, they chose Portugal as the venue rather than the UK!

As we flew into Porto, the view from the plane’s window showed ribbons of terracotta trail laid out in every direction, crossing rolling hills and vying for space with gentle streams on valley floors. Every so often the dirt was bisected by an equally serpentine stretch of tarmac. It looked like dual sport heaven. And on the ground those thoughts were confirmed – once we’d left the high-rise hotels and sprawling waterparks behind that is.

The F650 easily sliced through the light traffic, and around the palm-shaded roundabouts. The bike’s pretty low, easily manoeuvred, and although the power delivery is lumpy low down there is still that typical single-cylinder shove when you give the fuel injection some work to do. The notchy gearchange requires a good positive boot to get it to shift (no change there then…), though it was soon forgotten as the road opened out and speeds increased.

As they did, so too did the vibes, coming mainly through the seat and uncleated pegs. Little tingly blighters which, at first, I thought would give me pins and needles within a few miles. Whether I got used to it, or they subsided as the bike bedded-in, I couldn’t say but it wasn’t too long before I stopped noticing them.

The road ride gave a chance to have a play with the cockpit and the mix of digi computer and analogue speedo. A button beneath the display allows you to scroll through the two trip computers and the clock function. There’s also a useful countdown trip telling you how much further you can go when you dip into the four-litre fuel reserve. The analogue speedo is pretty clear and easy to use, though I’m not sold on the small bar-display digital rev counter that isn’t prominent enough to be of much use.

On a plastic shroud to the left of the dash is the button for the heated grips (if you spec your bike with them) and another for the hazard warning lights (if you opt for ABS). The switchgear is quality fare and although there’s nothing to make you coo with engineering-enthusiasm the overall feel is of a well screwed-together machine.

The screen is a relatively small affair though it did a fine job of deflecting the wind over and around my gangly frame. I can’t comment on how it’ll be on a long motorway run – thankfully we were spared such tedium – though even with the peak of my helmet pushed right up there was very little buffeting at speed. Incidentally, there’s no adjustment offered, so if you find different it may well be worth investing in the taller screen option.

G-Spot

Away from the near-deserted off-season resorts, the countryside proved to be just as quiet, though perhaps tranquil is a better word to describe it. Whitewashed houses gathered around ornate churches, with lemon and orange trees adding some colour to the palette.

Hitting the first trail I stood up only to find that the mirrors clashed with my wrists and that I couldn’t reach the rear brake lever. Unlike the 1200 Adventure, there’s no fold-down lever extension here to give it extra height, and without the correct tool to adjust the lever we instead simply bent it upwards to suit. Mild steel parts may look cheap but they’re pretty handy in situations such as this, and they’re easy to mend too. An alloy lever wouldn’t have afforded us such an opportunity. Little could be done about the mirrors (mounted on the lever perches) other than running the levers slightly lower than I’d like.

This short ride really served only to get us out to our camp for the night – a full day on the bikes was to follow – and we rocked-up at the location shortly before the sun dipped below the hills. Nestled in a clearing alongside a very lazy river, a row of olive green tents faced a Moroccan-style bivouac. It was a well-chosen spot.

The clear sky promised a chilly night, and by morning a matt white frost coated the bikes and any kit foolishly left in the open. Thankfully the campfire was smouldering just enough to be resurrected, warming cold digits and rousing us into action…

Barely quarter-of-a-mile from the camp lay the first obstacle of the day – fording the river. Though the waters were deep enough to cause soggy toes, they posed little problem to the GS as the air intake lives under the right-hand rad panel – very handy for heading off the beaten track, be it in the depths of Wales or on a continental jaunt.

From the riverbank the trail led off into the hills, constantly changing in elevation as it wound through scrubland and between arid fields. Changes in surface were fairly fluid, as one minute the ground would be smooth hardpack, the next you’d be picking a path through small sharp-edged rocksteps or skating across a coating of pea gravel.

Whilst a 21in front wheel would no doubt be more stable for off-road use, the BMW seldom felt compromised by its 19in front hoop. Rarely did the front-end tuck in the turns or twitch on the stones, in fact it was only when taking a rocky descent at speed later in the day that I felt any need to allow for the small wheel.

Although the GS doesn’t position you right over the front wheel, there isn’t that vague feeling you sometimes suffer from with big trailies. The bike was wearing non-standard Mitas knobblies, which doubtless helped it remain upright and unscratched, though that doesn’t take away from the fact that the G-GS is surprisingly easy to chuck around off-road.

This is even more impressive when you consider that the bike runs a mid/rear-mounted fuel tank (the filler’s on the right-hand sidepanel) that could so easily wreck the handling with a nasty ‘pendulum effect’, as the weight swings the back-end around. But it doesn’t. In fact, having this weight held further back than usual likely helps with one of the 650’s more pleasing traits…

Although we’d taken in numerous loose-surfaced climbs, nothing had really served to display the Rotax motor’s infamous tractability. Until, that is, we dropped into a valley to find our way out blocked by a bulldozer, its driver merrily turning the hillside into a terraced orchard.

Seeing the gaggle of bikes, he skilfully pushed a huge mound of soil over the sheer side of the track, teetering precariously on the edge as he did so, and backed out of our way, leaving the coast clear but a heavily chopped-up climb of loose soil and head-sized rocks.

Avoiding the boulders and holes left by the ‘dozer made for a challenging ascent, though despite the 200-kilo (or near as dammit) bike sinking down into the soft dirt, it clambered onwards like it was running caterpillar tracks.

This was arguably the most challenging riding of the day, and whilst it was easiest tackled feet-up, it’s reassuring to know that you can get your feet down easily when riding off-road on a big bike, especially if you’re short in the leg. At 780mm, the 650’s seat is quite low, though you can buy lower (750mm) or taller (820mm) should your lower limbs require. The higher seat will certainly make the transition from sitting to standing easier for those around six foot tall, and also give a slightly more comfortable riding position when seated. Incidentally, while we’re on the subject of personalising the 650, the cable clutch benefits from a span-adjustable lever, so riders with small digits can adjust it to suit.

G-Man

Between the trails the tarmac was little short of sensational. Minor roads presented a real challenge of constantly changing surfaces and occasional crumbling potholes, one even featuring a small ‘step-down’ jump where the road had begun to subside.

Still deep in the countryside, the busier roads were better surfaced but just as twisty. The occasional straight meant that you could wind the bike up through the gears to motorway speeds, though mainly you were busy chasing the vanishing point through sweeping turns and keeping the squirming rear-end in check as you braked deep into hairpin bends.

With relaxed geometry and the weight held fairly low, the handling’s predictable and steady. Mix this with supple long-ish travel suspension and the bike really rewards a smooth approach rather than a frantic chuck-it-on-its-ear style. The mellow power simply reinforces this. There’s something undeniably fun about wringing the neck of a low powered bike, even if you do need to plan overtakes well in advance.

The 650 doesn’t produce heaps of lowdown grunt, and the midrange seems to be followed by a slight dip before the power builds again at the top-end. As you might expect of a big and slightly dated single-cylinder lump, by the time you hit the rev limiter the power has long since started to wane, yet you do need to work the motor reasonably hard in order to maintain a decent pace.

Like the engine, the brakes aren’t overly powerful either. I’d describe them more as adequate really. The 650GS doesn’t feel its weight, and therefore it’s easy to forget that the twin-pot caliper and 300mm disc upfront are trying to haul-up something knocking on for 200kg, plus rider and anything else you may be carrying. However, the lever pressure is great, there’s plenty of feedback, and as such they work excellently on the dirt (or for the novice rider worried about locking the front-end on tarmac).

G-Force

Although the area was criss-crossed with epic trails, two really stick in the mind and serve to reinforce why the G-GS isn’t simply a low-cost commuter masquerading as a trailie, but a reasonably competent dual sport machine. The first of these was a real rollercoaster, running along the ridgeline of a series of small peaks and mixing hardpack dirt with large areas of rockslab, loose stone, and shear drops off either side of the track.

It demanded confidence in your machine and as we picked up the pace the BMW continued to deliver. In fact, it took everything in its stride, romping up the climbs and slithering through the tight turns, right up until it ran out of suspension travel on a steep, rocky descent. This is, after all, a trail bike which will doubtless spend much of its time on tarmac, and as such only runs 170/165mm (front/rear) of suspension travel, so it came as little surprise that clanging it through a series of short-sharp drop-offs at a reasonably fast pace would push it to its limit. Everywhere else the fairly basic conventional forks and shock were surprisingly capable: the action was plush and progressive, and they took far more abuse than I thought possible. Originally the back-end sat quite low, and winding up the preload via the remote adjuster gave some much needed ride height, as well as improving the handling to boot.

The trail culminated in a fast descent down to join a crossroads, where a modern metal signpost reminded us that many of the ‘trails’ are very much ‘unmetalled roads’, and are often the only way to get a vehicle into certain villages. The trail we’d taken was a more rugged route through the hills – for daily use most people would use the smoother, more sedate route lower down the valley.

The second trail turned out to be the final lane of the day, and initially ran between small pockets of agricultural land. Here numerous chicanes threaded between walls and bushes, and it was possible to steer the BMW through the corners with the rear brake and throttle. Away from the fields the track ran through large areas of scrubland, and became bumpier but no less twisty. The bike would launch off the humps, power through rainruts, and squirm into and out of corners, whilst all the time remaining more stable than it had any right to. Oh sure, it’s not what the bike is intended for, and there are certainly big trailies out there which are way more competent on the dirt, but the GS is tough enough to take such abuse and, unlike some ‘adventure’ styled bikes, is actually good fun to chuck around off-road. If all you ask of it is to whisk you down a Moroccan piste or along a rough Alpine col then it’s certainly up to the job.

Having spent much of the day stood up on the pegs, by the end of the ride the soles of my feet ached thanks to the skinny little steel parts which are neither on- nor off-road spec, and offer precious little comfort or confidence on the dirt.

Along with some bigger pegs, I’d also source some bar riders if I were racking up some off-road miles aboard the 650. Reaching the braceless (though not tapered) handlebars was a bit of a stretch when stood up as their positioning is clearly intended for road use.

Lastly, given the low-ish ground clearance a decent bashplate would be a sensible mod for off-road use, if only to give a little extra protection to the regulator-rectifier which sits in front of the motor on the right-hand-side. (Watch out for mud, dirt and road grime messing with those electrics…)

G-Out

Okay, so what we essentially have here is a lightly modernised F650GS – no bad thing but hardly ground breaking. BMW haven’t given it greater spec, nor made it appreciably lighter than the old machine (one of those twin rear silencers is still essentially a dummy..!). What they’ve really done is admitted that there’s a place in the market for such a bike, and reinstated the old bike with the kind of modifications it would probably have received had it stayed in continuous production.

I’d like to see the Dakar model return to the line-up (when BMW produced the original F650 they also sold a ‘Dakar’ model which featured a 21in front wheel and longer travel suspension) as the modifications didn’t overly compromise the bike’s tarmac potential yet gave it greater ability on the dirt. Like the 1200, an Adventure model could add a little extra depth to the range and would rival Yamaha’s 660Z Tenere in the ‘rugged, middleweight adventure bike’ category. Though it’s perhaps wishful thinking in a tough marketplace…

The Bavarians are marketing the bike as an introduction to the GS family, though it’s more than just a stepping-stone onto the twin cylinder models. It’s a fine machine in its own right and, it should be said, something of a bargain at just under five grand. You might want to add a few options and accessories to that which will obviously increase the price, though given the bike’s undoubted longevity it still represents a great mileage-to-money ratio. Bikes such as KTM’s 690 Enduro and Husky’s TE630 are more suited to the dirt, and Honda’s Transalp is easily a better road machine, though they’re in a different price bracket.

The G650GS isn’t a bike which gets you frothing with excitement, either in terms of looks or performance. But if there’s one thing is does really quite well it is, well, a little bit of everything…

Shopping List

It wouldn’t be a BMW without a list of options ready to go on at the factory, or be fitted by your dealer. Here’s what you can add to your G650GS:

Seat height reduction: £170

Heated grips: £230

ABS: £660

Alarm: £198

Centre-stand: £120

Power socket: £40

On top of these there’s also a range of accessories including panniers, a topbox, tankbag, handguards, crashbars, sumpguard, and the option of having it 34bhp-restricted to meet your licence requirements.

BMW G650GS

Price: £4920 (UK–2011) plus OTR

Engine: DOHC, fuel injected, twin spark, single

Bore & stroke: 100 x 83mm

Displacement: 652cc

Transmission: 5-speed

Frame: Steel bridge

Front susp: 41mm USD fork

Rear susp: Single shock with remote preload adjuster

Front brake: 300mm disc, two-piston Brembo caliper

Fuel capacity: 14L

Wheelbase: 1477mm

Seat height: 780mm (options of 750mm & 820mm)

Weight: 193kg (wet, claimed)

Contact: BMW UK on 0800 777 155 www.bmw-motorrad.co.uk