It’s Rust Sports battle of the big trailies, with the 2013 BMW R1200GS grappling the 2013 KTM 1190 Adventure on the backroads and trails of Norfolk…

One-litre adventure bikes: big machines in arguably the biggest motorcycle sector right now. And within the war for market share there’s a battle raging between old adversaries: KTM v BMW; Adventure versus GS.

In terms of sales figures there’s no doubt that the Germans had gained the most territory, though when tested head-to-head we often came down on the side of the more sporting KTM. Only now both factories have regrouped and launched new offensives, each with a new model.

What’s changed on the KTM? Er, everything! The 1190 Adventure is an all-new machine, with a retuned (to 150hp!) engine and revised gearbox lifted from the devastatingly rapid RC8R sportsbike, sitting in a chro-moly trellis. The chassis components are more tarmac-suited than on the old LC8 Adventure, with shorter 48mm forks and linkless shock, and a 19/17in wheelset in place of the 21/18in parts of the old bike. The rally styling has gone in favour of a more ‘conventional’ look, and KTM have added almost every gizmo you could think of fitting to a modern machine. There’s ABS, traction control, switchable riding modes, ride-by-wire throttle, electronically adjusted suspension (EDS – a £500 option), a slipper clutch, and an automatic headlight…

BMW haven’t gone quite as far, inasmuch as they’ve retained the character and styling of their old R1200GS. Much of the bike is brand new, you just need to know your BMWs to spot it. Take the engine for example. It’s still that trademark Boxer, with cooling fins on the pots. And indeed 65 percent of the cooling comes from the air. But it’s now ‘water’ rather than oil which provides the other 35 percent, focused on those areas which encounter the most ‘thermal stresses’, and there’s a pair of rads tucked neatly behind those silver front panels. Most of the internal components have been refined – a new crank, reworked cams with altered timing etc – and the old car-type clutch has given way to a more familiar multi-plate wet-type. The throttle is now actuated electrically rather than by cable, too.

BMW stiffened the frame and suspension, sharpened the geometry, and did you spot that the shaftdrive now mounts to the left side of the rear wheel, rather than the right? Yep, they’ve updated the Paralever design as well. And having done all that the Germans then added pretty much the exact same ‘rider aids’ to their bike…

Putting the two head-to-head demanded a roadtrip. The Alps? Marrakech? Some far-flung land where the locals still travel by horse and cart and where children stand and point at bikes as they whiz by? Almost. We chose Norfolk!

Click on any of the images above to see the full-sized version

Webbed Feet

We leave London under threatening clouds. Traffic stretches away into the murky distance, the white haze of faraway rain obscuring the horizon. It gets worse. As we leave a North Circular filling station the roads start to shine with the first drops of moisture, cars leaving glistening tracks on the tarmac. Rain on previously dry city roads, matched to heavy homebound traffic, aren’t the ideal conditions for the first ride on a 150hp machine, especially one set in ‘sport’ mode. Yet the 1190 feels incredibly manageable, with a smooth throttle response, as we wind northwards and out onto the A1.

Neither the rain nor the traffic subsides, and as we pass Stevenage the last of the sunlight fades and the heavens open like the cargo bay doors of a firefighting plane. We’re drenched in seconds.

The KTM’s handguards do a reasonable job of keeping my hands warm and dry, though like many – or almost all – adventure machines the screen doesn’t deflect all of the onrushing wind ‘n’ rain, and I need to duck down to send the stream of air and water over my head and around my shoulders.

You need to stop and undo two clips to adjust the screen on the Adventure. You don’t on the GS. So when we swap steeds at Royston the first thing I do is play with the adjuster on the right-hand side of the cockpit which slides the screen up and down in its mountings. I find a setting that almost does the job… but not quite.

Now all I need do is to locate the button for the heated grips. I know it’s there somewhere, but looking through a misty wet visor, and with switchgear fit to burst with buttons to prod and switches to rock, it takes a while to locate it. I’m overjoyed when the warmth starts seeping through my gloves.

To ride, the new GS feels instantly familiar. On these soaking wet roads it feels solid, smooth and dependable. What takes the most getting used to is that busy switchgear – BMW even resorting to a conventional, one-button, indicator switch rather than their much-maligned three-button system in order to cram some more functions onto each side of the bars..!

That, and the clocks. The KTM is a well laid-out joy of easy-to-read digi digits, with a large analogue rev counter in the centre of the dash. To the left is a panel for the various modes and settings, to the right is the speedo, with a small gear position indicator, fuel and temperature gauges and a clock. It makes up for their use of cheap-feeling switchgear and the small cubbyhole (a useful idea lifted from the outgoing Adventure) whose flimsy lid would fail quality control in a Chinese cracker toy factory.

Compared to the 1190’s, the BMW’s clocks are rather lousy. The speedo is an analogue unit with small numerals which aren’t particularly easy to read at a glance (and downright impossible when covered in raindrops) with a small rev counter positioned above. There is a digi display, and inexplicably its most prominent feature is the gear position indicator – it’s over half-an-inch tall! There’s also a fuel gauge and the bike’s riding mode, an odometer, plus various nuggets of info that you can scroll through including temperature, trip, mpg, average speed, and the date (annoyingly represented in the ass-about-face US style).

By the time I reach my digs I’ve warmed to the German bike, dashboard aside. In poor conditions you know where you are with a GS, even if you have no idea how fast you got there! It just gets the job done, smoothly and with the minimum of fuss.

Normal For Norfolk

Come morning-time, the rain has stopped but the clouds still threaten mischief. And the roads aren’t playing ball either – intermittently dry, damp or drenched, their worn-smooth finish gives the traction control a real early-morning wake up call.

I meet Al near the coast, and we cut inland to what we’ve nominated as the start of our route: the highest point in Norfolk. From there we’ll head west, taking in as many points of historic interest as we can cram into a day’s riding.

Heading east, the air begins to thin and the power drops off as we climb higher and higher. Yeah, right! At a dizzying 103m above sea level, the climb up to Roman Fort at West Runton isn’t exactly Pikes Peak, though it does offer a pleasant view out over the sea – were it not obscured by low cloud and steady rain…

National Trust have planted their flag atop the hill, laying claim to the small carpark, and surrounding wood- and heath-land. Despite the site’s name, and some old earthworks, there’s no evidence to support the Roman tag. Indeed, the official name is Beacon Hill, and it’s thought that the mound was more likely to have been historically used as a signal point (dating back to the time of the Spanish Armada) than a military outpost.

Geographically, the hill is part of the Cromer Ridge, which was formed from the material pushed up from the North Sea by the glaciers of the last ice age. Its wooded, sunken lanes, seem out of place in a county characterised by rolling fields and open skies, and a mile down the road agriculture once again dominates the landscape.

The BMW’s Boxer motor has lost none of its character or traits. It still wafts along A-roads with a deceptive turn of speed; the gearchange is still a trifle clunky; and at slow speeds, such as negotiating Cromer’s one-way system, you can just make out a tappety ticking from the exposed cylinder heads. Plus, of course, the bike’s facelift has done little to change the typically-GS appearance.

The KTM looks nothing like the old Adventure. And it’s worse for it. The candy orange paint and pink ‘1190’ graphics (yep, in the metal they’re definitely pink) I quite like, as there’s a certain late ‘60s/early ‘70s vibe about them. But in terms of the styling I think it’s on a par with Ducati following the stunning 916/996/998 with the weirdo 999. Except the 999 was sufficiently different from the norm that it stood out, even if it wasn’t well received, and has actually dated rather well. Heck, I even like it now. But after the 950/990 the KTM’s bodywork looks awkward and the back-end unfinished. Pretty it isn’t.

Steam Rollers

Parking above the promenade, the sea is a murky grey lapping unenthusiastically at the shingle, and no-one on the pier is plucking the famous Cromer crab from this chilly old dishwater. The whole scene shouts ‘out of season’.

We fuel-up, noting that the KTM has been slightly more frugal than the BMW (47 and 46mpg respectively) and head west. It’s a slow, stop-start affair, through small villages and vast caravan parks, past the Beeston Hump (and its comically sloping football pitch), smiling at the antics of the gundogs in the pick-up truck ahead, before we reach Sheringham.

You don’t have to be Dibnah or Martin – EVERYONE loves a good steam train. So when we spot the telltale puff of white smoke hanging above Sheringham’s station we pull into the carpark for a nosey. There, waiting to depart on the five-mile trip along the 126-year-old North Norfolk Railway to Holt, sits an old Welsh coal-hauling loco, building-up boiler pressure.

The air is thick with the oily scent of hot machinery and a sense of anticipation as two old boys shovel coal into a roaring fire. Then it’s a quick toot of the whistle and off they chuff, with faces beaming from the carriage windows behind.

We could play chase the train along the coast but it seems a little unfair on the old engine, with the new Beemer engine putting-out a claimed 125hp and the KTM packing a healthy 150. Instead we take-in the vintage ambiance of the station before unleashing those horses down the coast road.

The BMW pulls from nothing in an almost ceaseless surge of power which perfectly suits this road. Blind brows, hedge-lined turns and slow traffic are all easily dispatched with the minimum of gearchanges, using the torque to haul us along.

Unsurprisingly, the KTM’s sportsbike-derived engine is very different. It doesn’t seem to possess the same smooth bottom-end drive as the lower revving Boxer lump – it’s a smidgen grumbly at low revs and you need to get it spinning that bit more to really wake it up. But when you do, oh man, the turn of speed is unbelievable.

By the time it’s in the midrange – six maybe seven grand – you’re thinking ‘hmm, this things pretty swift.’ Then you hang onto that gear, twist the grip that bit further, and the Adventure goes bonkers.

Really, this thing is indecently fast. And I think it needed to be, not just to trump all of the other manufacturers but also to give it a real stand-out feature. Because the old Adventure enjoyed a decent powerplant and a chassis that willed you to play with it both on- and off-road. It felt quite unlike any of its contemporaries. By roadifying the 1190, it needed to stand out in this fierce sector. And only Ducati’s Multistrada runs it close in the power stakes…

Sadly the rain reins-in our fun, as Norfolk’s famous ‘big skies’ turn grey and the rain drives down hard. We’re out in the marshes around Salthouse and Cley now, and there’s nothing else for it but holing-up in a pub to let the worst of it blow over.

Blakeney has a choice of inns, and plaques on a quayside building bring the inclement weather into perspective. Each marks a water level from a serious flood, the lowest of which, in 1897, sits around chest height. That of 1978 is head high. And, worst of all, is the North Sea Flood of 1953, when a high spring tide and a storm in the North Sea on the night of 31 January conspired to lift the sea level far above head height.

Floodwaters claimed the lives of 307 people in the UK – from as far south as East London right up to Aberdeenshire. However, on this side of the Channel at least, it was East Anglia that was the worst affected. Such flood markers appear on various historic buildings along this stretch of coastline, serving as a stark reminder how vulnerable the area is to the power of the sea and a memorial to those who died.

From the sea to the air, and our next stop is an equally evocative slice of Norfolk history, one of its old RAF airfields. During WWII, the base at Langham was home to a number of squadrons whose roles included anti-aircraft operations, air sea rescue and bombing missions.

As with many of Norfolk’s old airbases, there’s not a great deal of the old infrastructure left now. The concrete runways and taxiways remain, though are now home to many thousands of turkeys cooped-up in sheds, and most of the buildings are long-since demolished.

However, one that remains is a curious black dome, 40 feet in diameter, stood by the roadside. Now afforded the protection of Scheduled Ancient Monument status, the concrete and steel structure was used to train anti-aircraft gunners during the Second World War. Preformed asbestos panels lined the inside, providing a curved ‘cinema screen’ on the dome’s inner surface, onto which they projected (using a specially developed projector, a series of mirrors and unique film reels) footage of approaching enemy aircraft. The prospective gunner set his sights ahead of the plane, allowing for its speed and that of the anti-aircraft shell, whilst the observers checked his aim via a projection of the gunsight and a yellow marker line, or dot, which appeared on the footage ahead of the plane as the ideal point of aim. A yellow filter, or yellow-tinted spectacles, prevented the gunner from seeing this guide.

Decades of neglect haven’t been kind to the dome, though work is now in progress to bring it back to its former glory. Quite a project…

Flowing, almost empty, roads lead us towards Wells-Next-The-Sea. Both bikes are wearing Conti Trail Attack 2s and they seem to be a good match for both the bikes and the conditions. There’s plenty of feedback on the damp sections sheltered from the drying breeze by high hedgerows, and enough grip on the dry lines to have a blast. I can’t think that you’d want to ‘attack’ any snotty trails with them, but on road-biased adventure bikes they’re fine.

I See No Ships

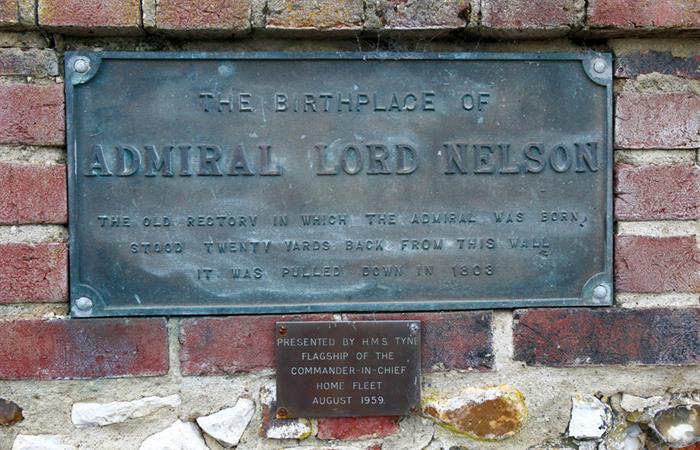

We couldn’t take a historical trip through North Norfolk without stopping-by the birthplace of the county’s most famous son. No, not Stephen Fry. Nor Alan Partridge. But as the roadsigns say as you enter Norfolk, this is Nelson’s county, and the admiral was born in the achingly tranquil village of Burnham Thorpe.

Babbling brook? Check. Quaint cottages bordering the road? Check. Pub opposite cricket pitch? Check. Compared to the hubbub of nearby Burnham Market – winner of the Britain’s Most Pretentious Village award many years running – it’s paradise.

The plaque marking Nelson’s birthplace takes some finding, being on the outskirts of the village, and it marks the spot where the village parsonage USED to stand. The building was torn down a couple of centuries ago but if you’re looking for longer-lasting memorials to Horatio then the pub where he drank and the church where his father was the rector offer plenty of authentic relics.

Back onto the coast road, and with dry tarmac to play on we can at last enjoy the snaking blacktop, where short straights link each section of turns.

Typically GS, the new 1200 rewards a smooth approach. Size-up the turn, tip-it-in, and the Beemer ploughs on through without fuss or fluster. Blatting down the straights, battered by a gusty wind, it does feel slightly more frisky than its predecessor as the bars gentle sway, though with the nigh-on diveless front-end it’s stable on the brakes and rock-solid mid-turn. On bumpy roads with an unpredictable surface it’s incredibly reassuring.

The KTM’s sharper and more nimble. It’ll carve a tighter line and is more eager to drop into turns. The steering damper tucked deep down inside the fairing prevents the 1190 from getting in a flap, and that’s pretty crucial when the front is barely grazing the tarmac in fourth gear, skipping the tops of the bumps like a powerboat on choppy ocean waves.

With both bikes running radially-mounted, four-pot calipers matched to big twin discs, stopping power isn’t brought into question. Perhaps a little more initial bite would be welcome from the KTM, though if you’ve just jumped off an old Adventure you’ll certainly not find it wanting. Get the lever span-adjustment right and one finger is all you need to get both bikes hauled-up in a hurry.

I See No Ships

We couldn’t take a historical trip through North Norfolk without stopping-by the birthplace of the county’s most famous son. No, not Stephen Fry. Nor Alan Partridge. But as the roadsigns say as you enter Norfolk, this is Nelson’s county, and the admiral was born in the achingly tranquil village of Burnham Thorpe.

Babbling brook? Check. Quaint cottages bordering the road? Check. Pub opposite cricket pitch? Check. Compared to the hubbub of nearby Burnham Market – winner of the Britain’s Most Pretentious Village award many years running – it’s paradise.

The plaque marking Nelson’s birthplace takes some finding, being on the outskirts of the village, and it marks the spot where the village parsonage USED to stand. The building was torn down a couple of centuries ago but if you’re looking for longer-lasting memorials to Horatio then the pub where he drank and the church where his father was the rector offer plenty of authentic relics.

Back onto the coast road, and with dry tarmac to play on we can at last enjoy the snaking blacktop, where short straights link each section of turns.

Typically GS, the new 1200 rewards a smooth approach. Size-up the turn, tip-it-in, and the Beemer ploughs on through without fuss or fluster. Blatting down the straights, battered by a gusty wind, it does feel slightly more frisky than its predecessor as the bars gentle sway, though with the nigh-on diveless front-end it’s stable on the brakes and rock-solid mid-turn. On bumpy roads with an unpredictable surface it’s incredibly reassuring.

The KTM’s sharper and more nimble. It’ll carve a tighter line and is more eager to drop into turns. The steering damper tucked deep down inside the fairing prevents the 1190 from getting in a flap, and that’s pretty crucial when the front is barely grazing the tarmac in fourth gear, skipping the tops of the bumps like a powerboat on choppy ocean waves.

With both bikes running radially-mounted, four-pot calipers matched to big twin discs, stopping power isn’t brought into question. Perhaps a little more initial bite would be welcome from the KTM, though if you’ve just jumped off an old Adventure you’ll certainly not find it wanting. Get the lever span-adjustment right and one finger is all you need to get both bikes hauled-up in a hurry.

We’re riding that bit harder now, so I switch the 1190’s suspension to the harder ‘sport’ setting… and immediately regret it. It’s just too firm for these roads, and every straight gives my kidneys a good kicking. Within a mile I’m back in the far more supple ‘street’ mode. The BM doesn’t feel quite so harsh in its firmest setting, though, likewise, we leave set on its middle setting for most of the ride.

At times I find the GS’s traction control to be a great safety net. Much of Norfolk’s road network is polished so smooth you can see your face in it, and mixed with the dirt washed/blown off the fields, the entrails of pheasants and a few squished sugar beet, it can take much of your concentration just figuring out the road surface. Knowing hat it’s got your back (-end) means you can devote more brainpower to reading the road and looking out for other hazards: deer, John Deere, and that old dear out for a bimble.

Yet at other times it’s a safety harness that’s fastened too tight, restricting your natural movement. On the ‘road’ setting you might expect it to allow the front-end to rise slightly under acceleration and the back-end to squirm as it fights for grip in the wet. It does neither. Try to effect a fast getaway, and if it senses the front wheel lifting even the smallest amount it’ll cut the power in an instant, slapping the tyre back into the tarmac and your plums into the back of the tank! And just to give you an extra kick in the goolies, if you haven’t backed-off enough it then lurches away like you’re back doing your CBT again. Even under modest acceleration out of a dry, bumpy, turn you can set the warning light flashing on the dash.

In comparison, the KTM set-up allows you more leeway. In ‘street’ mode it will allow the bike to carry the front-end without instantly cutting the power. I discover this, quite unexpectedly, whilst powering out of a third gear turn up a gentle rise. Before snicking fourth, the front starts to lift and it stays up for longer than expected. ‘Sport’ mode takes things a step further, as ‘dynamic’ does on the BM, or you could go the whole hog and switch it off completely.

Incidentally, both machines feature a ‘rain’ mode which really softens the power delivery and, certainly in the case of the KTM, cuts the available peak power. Given that both bikes’ traction control works well enough in the normal riding mode, I can’t really see the need to strangle them further.

To fully understand the various traction control and throttle response modes you really need to read the bikes’ manuals. Off-road settings offer less power and more slide, plus you can switch off the ABS or leave it engaged and, certainly in the case of the Katosh, you’ll still be able to skid the back-end. As long as you can match the level of control you want to a mode on the dash then the control is at your fingertips.

Cruise Ship

Heading further west, our route is punctuated by small coastal villages, and each speed limit gives a chance to relax. Here the BeeEm plays its trump card – cruise control. Never did I think that I’d want this on a motorcycle, but I soon found myself using it at every opportunity.

Slow for a 30 limit, flick the switch on the left-hand switchgear and the bike sticks to that speed until you brake or change gear, at which point it’s back in your hands. You can still roll-on the gas and the 1200 will accelerate, then when you chop the throttle it’ll return to whichever speed you set. Not only is it a brilliant way to avoid inadvertently straying over the limit, but on a long ride it allows you to rest your right arm. It confuses the hell out of onlookers, too!

This part of Norfolk features a number of trails, though a large ‘Road Closed’ sign keeps us off the most famous of all, the historic Peddars Way which dates back to Roman times. Nonetheless, we do get the chance to try a few gentle trails, and both bikes deal with them without issue. At these low speeds the BMW is easier to handle, despite being the heavier machine, thanks to a lower C-of-G and a narrower seat. Its wider and higher bars also give a greater degree of leverage. Meanwhile the KTM’s suspension copes better than the German Tele/Paralever set-up and the Austrians have given the Adventure a relatively low first gear so that you can pootle it along at walking pace without constantly riding the clutch. The 1190 aces the 1200 on off-road comfort too, as beneath its rubber cleats are a pair of regular dirtbike pegs. The Beemer also runs removable rubber cleats (which we remove as a matter of course even on the road), though underneath lay the most appallingly skinny, dated-looking footrests imaginable. Back in the office I compare them with those on our ’84 XL250 and they’re near enough identical. Eeurgh!

It’s worth noting that KTM having specced the 1190 with a tubeless tyre system, despite running spoked rims, making puncture repairs far easier than having to hoik the wheel out of a 220-kilo bike to repair a tube. Naturally the BMW’s cast rims are also tubeless, though they couldn’t resist making them slightly quirky and located the valve partway up one of the spokes rather than on the actual rim…

Such gentle lanes hardly challenge the bikes’ off-road capabilities, serving more to prove that dirt roads and fire trails won’t hinder either machine. We’ll wait for a ride on KTM’s R-version and, no doubt, a forthcoming GS Adventure model for a more thorough, muddier, dirt test.

The Wind in Your Sails

A fast blast through open farmland leads us to our final stop, though not before we break for tea and cake. The windmill at Great Bircham dates back to 1846 and is North Norfolk’s oldest working ‘mill. You can climb up through the workings to the very top too, and the reward for negotiating the steep wooden ladders is a cracking view across the gently rolling landscape. Or it would be were it not obscured by low cloud and a rapidly developing mist!

Not only do we miss out on the scenery but almost on tea ‘n’ cake too, as we arrive 20 minutes after the tearoom closed for the day. But we’re in luck…

‘I heard you coming’, states the owner, Stevie, as we turn around to leave. ‘Is that the new KTM? And the water-cooled Beemer?’ Suddenly the tea’s brewing and the choccy cake is being divided into sizeable wedges. What a star!

With LED lights cutting into the early evening gloom, the final few miles are another fast run to our destination. We could’ve chosen to end at the lowest point in the county, though it’s doubtless below sea level in the middle of some Fenland field. Or perhaps the seafront at Hunstanton, where this East Coast town actually faces west out across The Wash so that you can watch the sun setting over the water. Except ‘Sunny Hunny’ is looking pretty murky today. So instead we plump for the gates at the entrance to one of the county’s most famous landmarks, the Queen’s house in the country, Sandringham.

The end of the day is the time to comment on the bikes’ seats and there’s no doubt that the GS is the comfier place to be. As ever, you sit ‘in’ the BMW rather than on top of it and the German perch is soft without being soggy. It does a fair job of cosseting your behind. The KTM’s doesn’t. Although it’s nowhere near as dirtbike-like as the old Adventure, after the BeeEm you do feel higher-up on the 1190. The seat foam offers little resistance and you sink down through it to the point where you can pretty much feel the base. So it’s firm without being particularly supportive, and on a bike designed for racking-up huge distances we found it something of a let down. The 1190’s vibier through the pegs (mainly at low revs) than the silky GS too…

The adjustable riding position goes some way to making amends – the seat, bars, pegs and levers all allow you to fine-tune the ergonomics. Why more manufacturers don’t offer this is beyond me…

BMW do, albeit you have to spec your GS with optional adjustable footrests. There’s a total of three different height seats to choose from as well, each with a high and low position, and even the choice of a single seat rather than the stepped affair you see as standard.

Naturally both bikes can be kitted-out with an almost bewildering array of options and accessories, rocketing the sticker price. Indeed, tick all of the boxes on KTM’s online ‘parts calculator’, adding luggage, protection, exhaust, heated seats (!) and more, and your fully loaded Adventure will weigh-in close to £17,000!

The Big Finish

Five figure pricetags are now pretty much the norm in the 1000cc adventure sector and the spec sheets of these bikes go some way to justifying them. Of course, you don’t NEED such features to ride around the globe but these bikes are grand tourers as much as they are expedition leaders. If not more so.

With the kind of performance the KTM possesses, it’s no wonder the sportsbike scene is haemorrhaging riders. Here’s a bike that’s considerably more versatile and better suited to UK roads than a race-rep, yet retains the same adrenaline hit when you want to go for a blat.

The BMW gets the same job done in a different manner. It’s still more than quick enough for the road, yet its demeanour is far more unhurried mile-muncher than superbike on stilts. That said, on roads where the KTM is unable to exploit its power advantage the GS should be able to keep pace. It might not feel as lively, or as involving, but it’ll probably be there in its wheeltracks.

The pair are similarly matched in terms of which one I’d recommend, especially as both have foibles that let them down slightly. And much like the outgoing GS and Adventure, the choice really comes down to how much emphasis you put on enjoying the sporting nature of the KTM over the effortless accomplishment of the BMW. There were moments when I revelled in the Adventure’s mischievous nature and giggled as it turned the scenery into a greeny-brown blur, and others when I was glad that I was aboard the smoother and more comfortable GS. If I were pushed then I’d probably opt for the ultimate performance of the 1190, but if you really can’t decide between the two then, frankly, you wouldn’t be disappointed with either. I wonder if the sales war will be so close fought…

Thanks to: Scott Grimsdall, Ross Walker, Vines BMW, and Clive Hoy www.tricountymotorcycles.co.uk for their help with this feature.

KTM 1190 Adventure

Price: £12,595 (as tested, with EDS, £13,095 (2013))

Engine: 75º, fuel injected, liquid-cooled V-twin

Displacement: 1195cc

Bore & stroke: 105 x 69mm

Gearbox: 6-speed, with slipper clutch

Frame: Chro-moly trellis

Front susp: WP USD fork, EDS electronic-adj (190mm travel)

Rear susp: WP monoshock, EDS electronic-adj (190mm travel)

Front brake: Twin radially-mounted, 4-piston Brembos, 320mm discs, ABS

Seat height: 860/875mm

Wheel size: 19/17in

Ground clearance: 220mm

Fuel capacity: 23L

Calculated range: 238 miles (mixed riding)

Weight: 228.9kg (wet, claimed)

Contact: KTM UK on 01280 709500 www.ktm.com

BMW R1200GS

Price: £11,395 (as tested, Touring Edition, £13,815 (2013))

Engine: Fuel injected, liquid-/air-cooled flat (Boxer) twin

Displacement: 1170cc

Bore & stroke: 101 x 73mm

Gearbox: 6-speed, with shaft drive and slipper clutch

Frame: Chro-moly twin section trellis

Front susp: Telelever (190mm travel)

Rear susp: EVO Paralever (200mm travel)

Front brake: Twin radially-mounted, 4-piston calipers, 305mm discs, ABS

Seat height: 850-870mm (790-840mm with low seat/low susp options)

Wheel size: 19/17in

Ground clearance: 195mm

Fuel capacity: 20L

Calculated range: 202 miles (mixed riding)

Weight: 238kg (wet, claimed)

Contact: BMW UK on 0800 777 155 www.bmw-motorrad.co.uk