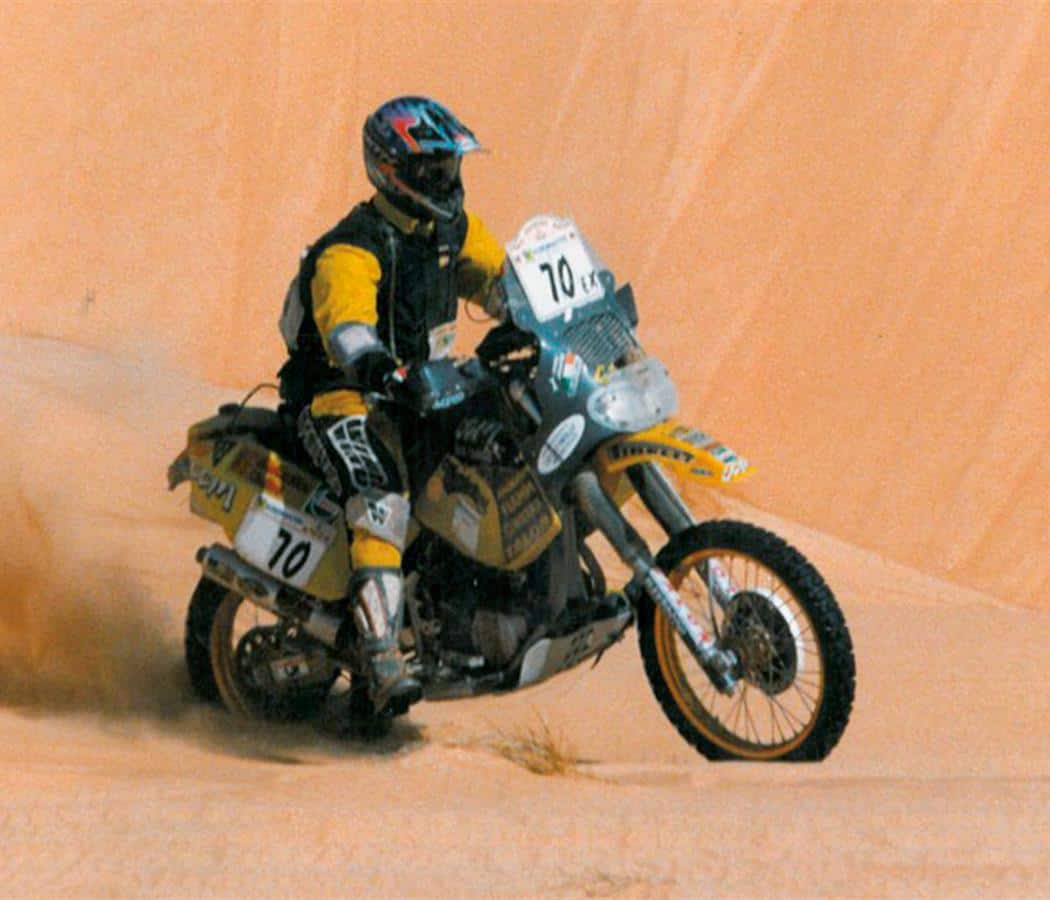

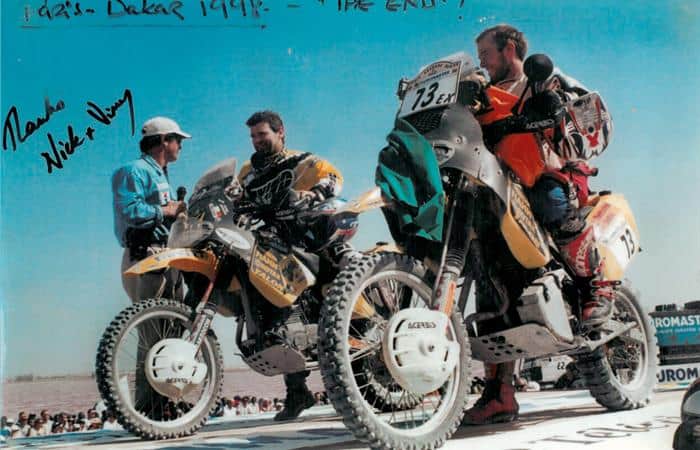

Any Dakar is tough. Fans and journalists naturally call it ‘brutal’. But is it? In fact the Dakar has been tougher, possibly far tougher. On its 20th anniversary in 1998 only 23% of the bike entry finished, just 41 riders. Nick Craigie was one of those 41. This is how brutal looked in 1998…

DEFINE BRUTAL

Despite 16 years and 8000 miles between them, the 2014 Dakar was strangely similar to the 1998 edition – Stephane Peterhansel fighting with Nani Roma for the win. Only in 2014 these two Dakar aces were driving cars, whilst back in 1998 they were still on bikes. Roma on one of the then-new KTM rally bikes (he’d DNF), Peterhansel on one of those Dakar behemoths of legend, a mighty Yamaha XTZ850TRX (notionally a Super Tenere, but in reality a factory-built special of outlandish proportions). Peterhansel won his sixth Dakar that year, beating Cyril Neveu’s tally to become the most successful Dakar racer of all time. He still holds that distinction today, now with 11 wins having taken five more in the tin tops.

The 2014 Dakar has also been called a return to the rally’s old ways – for being the toughest in years. Two marathon stages, where days are played out back-to-back without overnight team assistance, have put some self-reliance back onto the riders, and increased technicality on the route – exploiting the capabilities of the new lighter, skinnier 450cc race bikes – mean riders’ skills are truly tested. The term ‘brutal’ is much overused these days (along with ‘athlete’, alas), but certainly the Dakar’s extreme credentials have been reinstated.

January 1, 1998

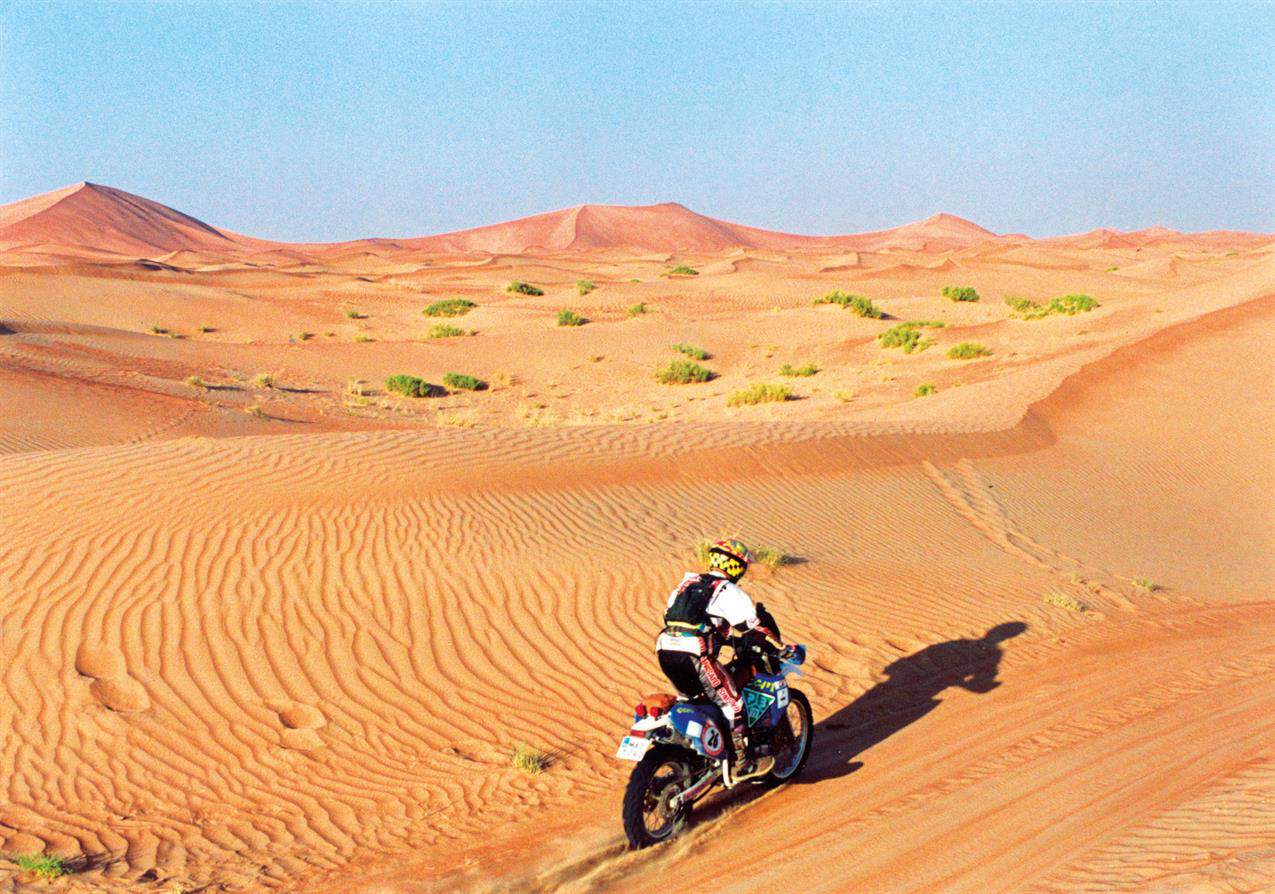

There will always be those who say the true Dakar took place on the African continent. They have a point, as this was, after all, the original concept – founder Thierry Sabine’s love of the Saharan region, and of motorsport, brought together. And while the African rallies were never days of innocence, those were the days when the organisation focussed more on the competitor than the media. There was no finishing at 3pm so all the end-of-the-day interviews could be conducted in sunlight, in comfort. First priority was to test the competitors and the media simply had to do their best to fit around that. And those were the days when a bivouac was exactly that, just a handful of tents in the desert, not five-acres of hard-standing with team trucks, motorhomes, media suites and VIP hospitality units.

‘There was a magic to the African events,’ remembers Nick Craigie. ‘And a loneliness.’

Craigie, a keen enduro rider (then and now), had decided he’d ride the 20th anniversary of the event. He’d ridden the 19th edition, in 1997, effectively in preparation, but had been forced out after eight days with engine problems.

‘We’d taken advice that the CCM-Rotax motor ran best on Castrol R40, a vegetable oil. That was probably true for short events [such motors were used extensively in American flat track racing] but with the extended hot running in Africa this led to the carbon build-up in the engine – particularly on the small-ends. That stopped my bike, and those of Adrian Lappin and Vinny Fitzsimmons. Disaster, but lesson well-learned.’

With the 1997 edition always intended as a warm-up to the 1998 rally, Craigie indeed learned the lessons and came back the following year as part of an all-Irish four-man team on CCMs.

Craigie remembers the first two days – still in Europe – being as tough as any. The start then was at the Place d’Armes, Versailles, France, and being mid-winter it was a cold 937km ride on day one, sub-zero all the way. Day two was another 1182km of freezing temperatures, before day three finally found the competitors at the Mediterranean port of Almeria.

‘I made the mistake of thinking that was the cold over with at that point. I dispensed with my cold weather kit, it was the ‘warmth of Africa here I come!’”

Only Craigie had overlooked the small matter of the Atlas mountain range…

‘That third stage, to Er Rachidia, was probably my worst day ever on a motorcycle. I’d already ridden for hours in -4ºC temperatures through France, but now I had the same temperatures while trying to ride over the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I didn’t have my warm gear anymore and with strong winds the windchill effect was huge. It was six to seven hours, riding completely on my own, just swearing at myself, trying to ignore my numb fingers and shaking body, trying to keep going. I was lucky, we saw some afternoon sun and that was like heaven. The little warmth that it offered got me through. In all it was a 14-15 hour day’s ride. I would have some very tough riding in the desert in the days to come but mentally I’d still rate that day, freezing in the mountains, as about the worst.’

Fuel Runnings

The fifth stage would prove the ultimate test. It was super-long day, 1050km including a lot of sand dunes as the competitors crossed the famous Erg Chebbi and more.

‘The deep sand was really hard going and forced the bikes to drink fuel, we were using fuel at a rate of to 7km/litre which, sustained, would have dropped our effective range from around 450km to barely 300km. The organisers hadn’t allowed for this and set the refuel too far out. There was no borrowing fuel from another competitor – everyone was trying to conserve every drop they had.

‘Our Dakar could have ended there – as it did for so many – but we found a solution by the three of us CCM team-riders working together. We effectively pooled our fuel, putting it all in the one bike (Adrian Lappin’s) and he rode on to the refuel. There he filled every tank he had and came back, riding the course in reverse, to share out the fuel. It was a high-risk strategy – he could easily get lost, breakdown, crash, certainly not find us – but it was all we had. Fortunately he did find us, but it had taken four hours and an incredible 350 additional kilometres riding for Adrian.

‘And it’s at that point, at about 5pm in the late afternoon, when the Dakar rally changes. Dusk comes quick, and it’s pitch black before you know it. That changes everything. A distance that takes you one hour in daylight takes you four in the dark. You can imagine the navigation is a nightmare. At 6pm at night we calculated we had 450km to the end of the stage.’

The team ploughed on through the night, and even saw the dawn come up, before reaching the bivouac just as the first competitors set-off for the sixth stage. For the CCM teammates there was just enough time to refuel, grab a snack to eat and line-up to start the next stage.

‘We stayed together after that. It wasn’t easy and again we hit trouble with night riding. At one point Vinny Fitsimmon’s lights went on the blink. We were each on our own sand dune at the time. I stopped, went over to him to help, when I got back to my bike I sat down and immediately fell asleep. I only awoke when Vinny came over and kicked me, his lights now fixed. “If you sleep now you’ll never wake up,” he said.

‘That stage we finished at 4 or 5am’, says Craigie. ‘Then it was, within an hour or two, time to be starting on into the next stage.

‘We got two precious hours sleep that time, but it was essentially 72 hours riding non-stop – we just had to get to the rest day.

‘So many things would happen, were always happening. On that last stage before the rest day we found Si Pavey [also on a CCM], he’d had a horrendous crash and was just gaga with concussion. We stuck with him and got him un-gaga enough to ride his bent bike between me and Vinny. We got him to a checkpoint and told him to stay there until the morning; with the next day being a rest day he could ride-in in the morning and still be in the rally. That was day nine with 11 still to go!

‘Of course the rest day was anything but, we spent the day changing the engine in my bike, although when we got the motor home and checked it was fine, it would have done the whole rally.’

Fear and Loathing

The dangers in rallying come from all directions. One particularly nasty danger is that of the car racers. As each day the bikes lead off it happens that the faster cars that follow will overcome a fair proportion of the bike entry somewhere on the course. Getting passed by a car on the road is no big deal but in a desert rally it’s an altogether uglier experience…

‘If there’s one safety regulation that I’ve wholly welcomed in the rally it’s been the Sentinel system for warning bikes of an overtaking car. When cars overtake it’s the most dangerous moment in the rally. They kick up so much dust that for a long while you’ll be riding blind and in that time you could hit a rock, drop into a hole – essentially have a big crash. You might then slow down but that only increases the danger as the next car will be rushing up on you and you’ll be a very slow moving target. Mentally the stress of knowing they were coming, waiting for the sudden explosion of noise and blinding dust, it was extreme, very very scary, and a fear we would face every day. The only answer was to ride off the piste, literally a good half-kilometre off the track, until they’d gone through. Of course, that slows you down massively. On-track you could be doing 100km/h, off-track you’d be doing 20km/h!

‘It eventually happened that I got run over, too! We were in a dune section and there you’ll zig-zag your way through. I saw this Schlesser Buggy coming, he saw me too, but as I went over a dune, he just drove straight on over the top of me. Me and the bike were completely underneath him, I was looking up at his car’s sump. Obviously I wasn’t very happy, but he just backed off and drove away, leaving me and the bike laying there. I found him at the bivouac that night and told him my feelings on the matter!’

Get Lost!

1998 was the first year GPS was adopted across the board for Dakar. The organisers supplied an ERFT GPS system.

‘Of course mine didn’t work. It would work in the bivouac, I’d get about five minutes out from the start and then that was it, it would go off for the rest of the day. The technical team from the organisers tried again and again to sort it – in the end they thought it was the frequency of the bike’s electrical circuit that was stopping it. So instead I went by the roadbook and looking at the tracks on the ground, or following the dust clouds. I’ll admit I wasn’t a very good navigator.’

Even with GPS there would be challenges. Craigie remembers winding on his roadbook one day and the message read “Next 358km – navigate by sight”!

‘Another day we were suffering what I guess was a form of snow blindness. Even with tinted goggles the bright sun off the sand burnt your retinas. I was riding with Adrian and we’d have to take it in turns for one to lead while the other rested his eyes by focussing on the lead rider’s rear mudguard. When he couldn’t see anymore we’d swap around.’

And when the bivouac was finally reached – in the dark – it was always hit and miss as to what awaited the riders.

‘We had a support mechanic and the girls came too, but we’d only meet-up with them probably every third day as they needed some form of landing strip for the planes. There was also no way the support trucks could keep up with the rally and get to every bivouac. It was too difficult. So most of the rally we did our own maintenance.

‘At the bivouac there’d be a big tent with carpets but by the time we’d arrive all the top riders and drivers would already be in their sleeping bags in there – no room at the inn! So we’d do our maintenance work then climb into our sleeping bags next to our bikes and throw a mosquito net over our heads. There was never much time to sleep…’

The Hurt Locker

Craigie was lucky he had only the one big crash. ‘It was late in the rally. I was going too fast through some fast whoops when everything bottomed and I got pitched. I was flying through the air thinking, “this is going to hurt”. But I was lucky, I was okay. The bike was a bit of a mess, and the lights and cowl were pointing in the wrong direction. But again I was able to get in behind Vinny [in the dark] to get to the finish.’

Reaching the finish at Lac Rose was, of course, every Dakar rider’s dream. It’s just that getting there was a nightmare…

‘You never recover from the setbacks in the Dakar. By the time we’d got to the rest day we were knackered. But from there on we only got more and more tired. You’re ignoring the kilometres, just counting down the days. Often you’re riding in a haze, not really connected, then something will happen, to startle you, the adrenaline would kick in and you’d be okay for a while.

‘By the finish I was in a state of total collapse. I’d lost two-and-a-half stone and it took me a long, long time to get back to normal. For the next eight months I remained physically exhausted. My hands and arms were in tatters. Some might recover quickly but it was a long time before I felt my normal self again.’

Craigie returned to rallying last year, riding the Merzouga Rally, again CCM-mounted, this one comparatively modern, with a Suzuki DR-Z400-based motor.

‘Rallying has changed. At one point in Morocco I was stopped near a checkpoint when I think it was Sam Sunderland who raced passed me – he looked and rode like a motocrosser. He was going full chat in the dunes, like nothing we could do back in the day.

‘But I’m not the man I was back in the day either – I was having to stop, take my goggles off and put my reading glasses on to read the GPS!’

Craigie is in a fairly rare position, with experience of rally racing in the 1990s and today (if not the modern Dakar). But like many a competitor with experience in top level sport, he knows that to make comparisons between eras will always be unrealistic.

‘The Dakar today is very different, I wouldn’t say it’s any easier – and I really feel for those competitors who were knocked out early this year. There’s a lot of preparation and money goes into riding the rally, so it’s tough to only get two or three days of it. But I often wish the riders today could experience what we did in Africa. Harder or easier, it’s not something I’m going to debate… times move on, bikes have developed. All I can say is it was special and I’d love, even now, to be able to ride that Paris-Dakar route again. For me, only Africa can be the Dakar.’

Risk Assessment

The internet didn’t exist when the Dakar first ran in 1979. (And even in 1998 it wasn’t as omnipresent as it is today.) So when calamity befell a participant it fell to the news media to tell the story via television or newsprint. And through straightforward pub discussion or finely crafted ‘letters to the editor’ the whys and wherefores would be debated. Today a rally accident is known almost instantaneously around the world (usually transmitted via social media), whereupon of course it is immediately debated on online forums, often in something of a belligerent – mostly uninformed – manner.

Let it be said, then, that the Dakar Rally does have a risk profile, though statistically it’s not a horrendous one. In its 35-year history some 27 competitors have been killed. Over the same period the Isle of Man TT Mountain Course has claimed 117 lives. In 1998 no competitors died but five Mali locals were killed when a competitor’s car was in a collision with a bus. Another year one competitor died and an Argentinian journalist and his passenger were killed when they rolled their car while following the rally.

In fact spectating – or being in the environs of the rally – is actually more dangerous than being a competitor. Over the history of the event some 41 non-competitors have died as a result of rally-related accidents and that number includes five journalists and the rally’s founder, Thierry Sabine.

Notwithstanding, if we scale up the numbers, it would seem the risk of death in the Dakar is barely greater than that from heart-related diseases. You might want to try that one on your health insurer at the next renewal!

Heavy Metal: 1998

• Stephane Peterhansel’s Yamaha XTZ850TRX

Water-cooled, twin cylinder, 850cc TRX850 roadbike engine (tuned), producing around 80bhp – good for 180km/h – in a one off-chassis. Carried 60-litres of fuel – 35 litres in a pair of forward tanks, 25 litres in a rear tank. Weighed circa 200kg.

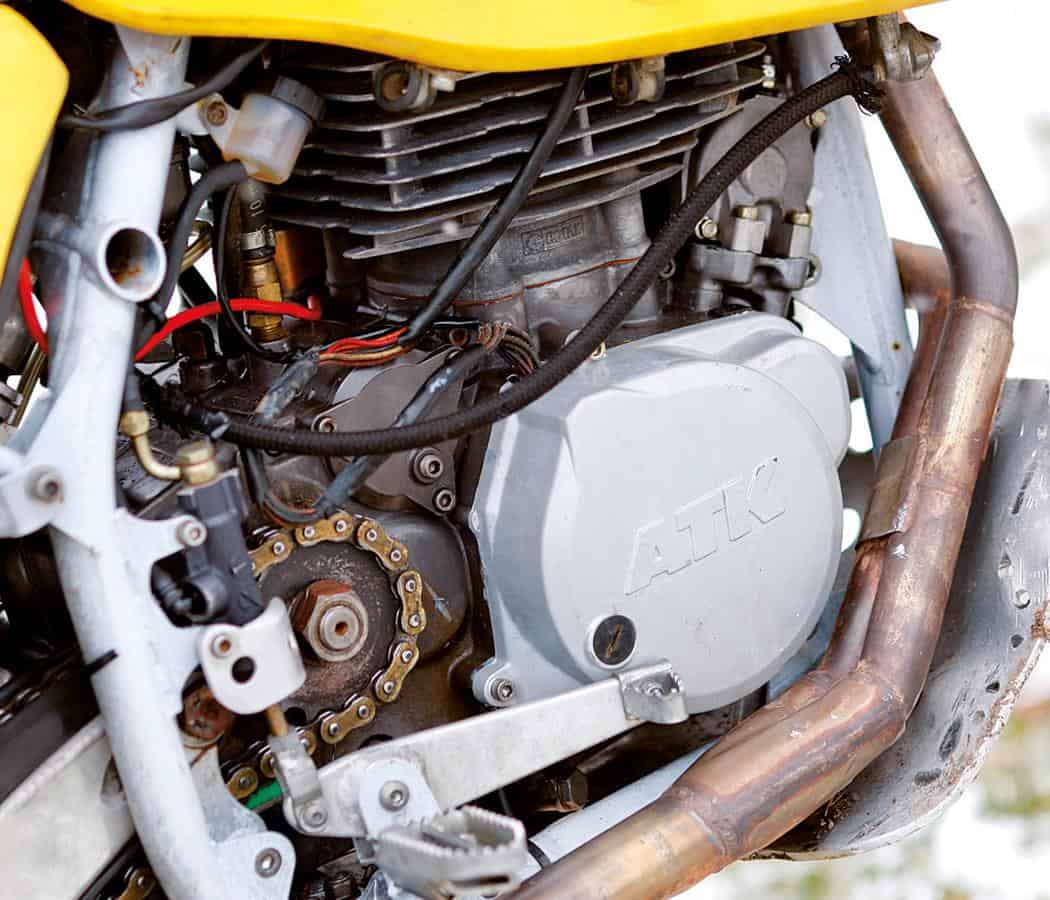

• Nick Craigie’s CCM C27 604

Air-cooled, single cylinder, dual start 600cc Rotax motor, producing around 50bhp, with a top speed of about 130km/h. Standard CCM frame but double-welded with extra gussets for strength. A total fuel capacity of 45-litres. Weighed circa 240kg.

2014

• Marc Coma’s KTM 450 Rally

Water-cooled single cylinder 450cc engine, based on both motocross and enduro engines, producing around 60bhp – top speed circa 160km/h. Trellis-type frame. Fuel capacity 35-litres. Weighed under 150kg