NATHAN MILLWARD

2015: Nathan Millward had ridden Sydney to London, and New York to Alaska on a 110cc ‘postie bike’. But two books later do we really know him?

Nathan Millward’s story starts much like most of ours. A working class family. A father teaching his sons how to ride. An auto 50 exchanged for a 60cc motocrosser, then an 80. The family together enjoying weekends united at a motocross track, sons riding, father as mechanic, mother as flag marshal.

Ten years later there’s the 50cc road bike and the freedom of the highway, albeit at 32mph because that’s all the AR50 will pull. Then a year later real freedom with a TZR125R. Then the first crash – and write-off. Nathan following the time-honoured career progression of the motorcyclist.

Jump another decade and we’re in Sydney, Australia. University education completed – with a masters in business studies – but no great career. And after nearly a decade without a bike Nathan has one again – an ex-postal service Honda CT110 step-thru. It’s all he can afford. He’s on a tourist visa and working cash-in-hand in a sandwich bar.

Now comes the adventure. The tourist visa is nearly expired, the relationship with the girl he’s come all the way to Australia to pursue is failing. He has to leave the country, pretty much on both accounts. He has a return air ticket in his hand, but he has a postie bike parked in the yard.

“With the visa expiring and the relationship not working I needed to leave the country within less than a month. I could have flown home, but I didn’t really want to go home, that felt like failure. But I had to leave. I had a bike… I had a rough idea of what I needed to do. I didn’t have enough money, but I had credit cards. I thought, ‘it’ll take about five months, I’ve got £5000 between cash and cards, I’ll give it a go’.”

It was a Thursday; on the Sunday he set off.

CROWD PLEASING

Five months was optimistic, as it turned out. So was the idea of making the journey on the postie bike. At least on that postie bike, it made Sydney to Brisbane but with knocking big end bearings it wasn’t going much further. Still no falling back to the 747 option, instead an upgrade – to a newer, fresher postie bike. And for us dirt bike fans, this one was equipped with an XR200R fuel tank, so it had two fuel tanks – proper overlanding style.

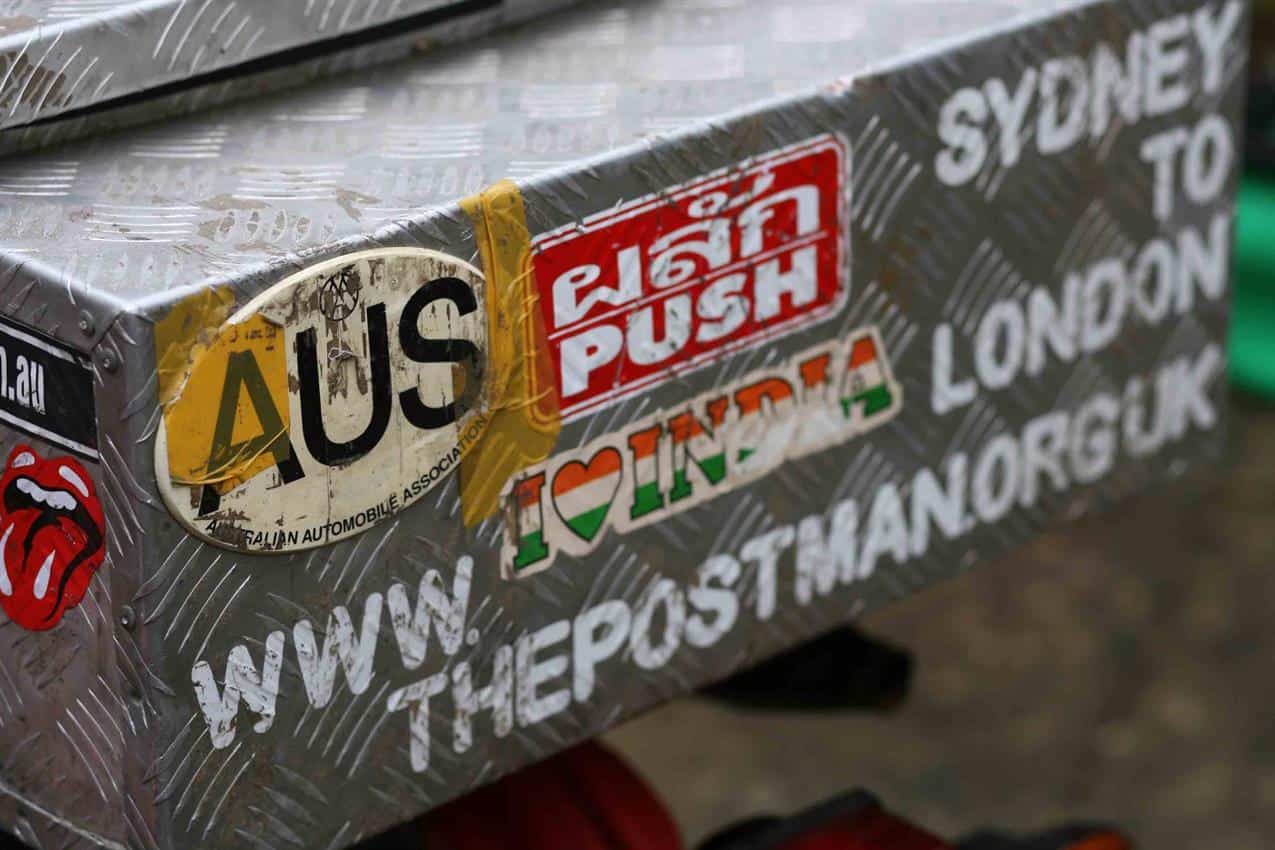

Nine months later then: London. Still in the same Converse baseball boots he wore when leaving Sydney. Epic journey complete, and he’d even attained a modicum of fame given some press coverage and the modern communication portals that comprise social media, be it forum or Facebook. He’d blogged, posted, made video diaries, as is the way of the modern adventurer.

He’d lived the dream. And through the internet become a hero…

“At the outset I thought this journey is happening, I’m going to do this, maybe it’s worth filming. People want to know what you’re doing, you want to show them what you’re up to. But you also want to look cool, want to reach out to people, to an audience. It’s ego, you are doing it to look good, cool, no different to daily Facebook – you only put the good stuff up, don’t you?

“Initially I set out wanting to put on a good face, say the right things, make it sound amazing. You want people to follow you, you’re posting on forums – and you’re thinking ‘people are watching me, look how cool I am, the coolest kid in town’. When I started posting on ADV Rider they went crazy for it, they really tuned in to the ride report. Every day it was ‘how’s it going, have you got any videos, any photos?’

“I guess it took me to about the time I was in India – halfway through – to realise that chasing an audience is to the detriment of the trip. You can’t do both. You can’t have an organic carefree trip as well as maintaining a blog. The blog almost becomes a job on the road and you realise that the more you give people the more they want and the less likely they are to be satisfied with what you’ve given them. You can do blogs, you can do posts, you can give them your soul but they want more. And if you don’t give that to them then the next day they could soon turn on you. People who were supporting you start being critical.

“So it was at India that I realised having an audience watching you go through the motions of an adventure is probably one of the worst things. Yeah, people tune in, they might read your posts, watch your videos but they’re not friends, not family, they don’t ultimately care, they just want to be entertained. And as soon as you stop entertaining them they’ll turn on you. So that’s why from India onwards I effectively turned the camera off.

“And when I look back at the footage from that trip I hate it, I hate what I say, hate what I am, hate watching them, wishing I’d done it differently. It was part of the experience, part of learning: I’m going to ride home to England – look at me! It was that: Watch me ride across the world.”

REVEALING TRUTHS

“The videos show what you want people to see, same with blogs, even group emails, you are presenting an image of the trip that is a lot of the time false. A few of the videos I shot I was very honest and if I was miserable and sad I recorded that, but I don’t like those anymore than the others!

“Looking at those blogs and the forums – and this was probably why people turned off to me – I started to reveal that the big trip isn’t necessarily a bed of roses, sometimes it’s actually a shit experience. I told them, I’m in the middle of India, there’s 15,000km to go and I’ve had enough, I’m running out of money. I can’t fly home because that’s quitting, but I don’t really want to ride any further, I’ve had enough. I’m here now and it’s shit.

“And that upset them, people don’t want to hear that it’s shit, they think their life is shit and you are living the dream, because there’s a pretty backdrop to your photos. They see what they want to believe, that one day they’ll do what you are doing and be happy – and you know full well in your miserable hostile little room in Delhi that you are a long long way from happiness. The people back home sat with their feet up on a Saturday night, drinking tea, eating angel delight – they’ve got it good. It’s all about perspective really.”

This is life, a series of moments, decisions that can lead us one way or another. It might be from schoolboy motocross to a trade apprenticeship, to weekend racing, to enduro, to a relationship, to a young family, to trail riding, to a week’s holiday with mates on bikes. Or from schoolboy motocross to Uni, to winter holiday jobs in the Alps, to summer holiday jobs in Greece, to travel, to Australia, to a relationship that struggles to hold its footing over the shifting sands of temporary visas and casual employment, to a long overlanding trip and – curiously – to media interest and even fame.

Through moments and decisions, so few consciously planned and strategised, it’s possible to find yourself either in the heart of family, holding down the day job wondering what it would be like to take off, to be free, or, alternatively, alone on the edge of society, regaled and cheered for your achievements while you teeter on the edge of the abyss.

“I got back to England and I was in a very uncomfortable position in myself. If a big trip like this doesn’t make me happy what do I do? Where does it go from here? If this trip doesn’t give me meaning or purpose or contentment – and the trip was the biggest thing I could imagine doing – then what will?”

A book! Writing a book – as cathartic a remedy as ever known. If only it was that simple; this is after all real life, not a film, not the la-la land of social media. All the same, Nathan did turn author, penning ‘Going Postal’ (now in its second edition, renamed ‘The long ride home’).

“I had to write the book because I was commissioned to write it while I was in India. In Thailand I had printed 100 personalised postcards and sent them to every media outlet I could think of, explaining ‘I’m on this trip, do you want a feature, or can I write anything?’ I sent one to the Sydney Morning Herald and they replied yes, 500 words on the journey so far, please. They paid $250 – cool!

“Then the Sydney radio guys read that out – all good for the ego. Then the commissioning editor at Harper Collins in Australia emailed and said he’d read about me in the Herald – ‘sounds like cool trip, do you want to write a book?’ So I signed a contract there and then and they paid me the commission in advance, which effectively paid for the trip home.

“But it meant when I got home I had four months to write the book. That turned into eight months as I struggled and we pushed the deadline back. I’d got home completely confused about what I felt, realised the trip wasn’t that important – the relationship was important, the girl that was in Australia, that I’d had to leave behind, that was important. But that was over too. So I was full of regret, sorrow and sadness – and I had a book to write, whether I wanted to or not.

“And it wasn’t a motorbike trip, it was that moment we all have, the point in life where everything has gone beyond our comprehension, your emotions are running wild, you’re angry, frustrated, you’re uncertain about everything – and you leap out the front door and run off down the street. Only I happened to be on a motorbike, running-riding back to England. It was an explosion of energy. I had to try and contain that in a book and make sense of it. And I had to feature somebody who was paramount to the trip without giving too much away about them. The girl, or the failed relationship, that made me angry, without that there wouldn’t have been a trip – so there couldn’t a book without her. So how do you write about somebody without turning them into literature? It was a frustrating, mind-bending experience trying to put it into print.

“I could have done without the book, to be honest. But the book helped me make sense of the period, it forces you to reflect, only that is not always good. I regretted the trip and the book.”

RUNNING TOWARDS THE LIGHT

And so what do we ask the intrepid traveller on their return. What we always ask: ‘what’s next?’

“It’s frustrating when you do a trip and people ask where are you going next. I think: why don’t you go somewhere next, why do I have to go? I’ve done my trip.”

If there was a dark side to the travelling, there was a dark side to the stopping too. Perhaps it’s related to that question we all ask ourselves – what have we achieved? – only after going to such extreme lengths, to have searched for, well, redemption, then to have come up empty-handed must drive a soul to darker depths. Nathan explains such in the prologue to his second book.

I hit the bottom when severe burning sensations in all my bones took me to the doctors, and the MRI scan said nothing was physically wrong, which made the doctor ask: ‘how do you feel in yourself?’ To which I cried and told her at times I just wanted to die.

‘Do I need to worry?’ she asked.

‘No,’ I said, ‘I’m too indecisive for that’

We both laughed.

Nathan’s depression lasted for two years. Eventually he arrived at a juncture.

“The only way out, I felt, was to get on the bike and ride.”

Again just days separated the decision and the action. Nathan and his postie bike flew to New York with a plan no more evolved than to head west.

“It was a last roll of the dice. I was nervous about it, but I didn’t know what else to do. I just turned to the road and hoped it would be the right decision.”

Nathan explained he chose America, chose to ride east-to-west, on account of a sub-conscious preference to ride toward the setting sun. Hence ‘Running Towards the Light’, the title of his book, the physical action, but also the metaphor for his mental state.

“The first few weeks were crap, camping wild, not knowing where I was going, realising the bike was way too slow (for American traffic conditions) – you’re a liability in the traffic. Then I’d go through places like Detroit, through the inner city suburbs – it was grim. Chicago the same. Not a nice place to see, it depresses you, and for a person in a depressed mental state to see the slums of America it was just brutal.”

From such depressing beginnings the trip picked up.

“The energy of the Sydney-London ride went from great to downhill. The second one started low but rose – it was the cure of the road. I describe it in the book – some people turn to the bottle, others turn to the road. What the trip allows you to do, if you are full of anger, full of frustration, full of venom, is hit the road and in so doing release it, you can ride day and night, ride as hard as you want, take chances, really let off steam. You can’t do that day to day, you bottle it up, you feel like punching yourself, going mental, but on the road there’s nothing there, just the ride. So when I got into the west, Utah and Nevada, the wide open spaces, the rage drained away – it was a great therapy.”

The therapy was working, but the ultimate cure didn’t come until Nathan, having crossed east-to-west, then ridden north through western Canada, was deep into Alaska.

“I met three guys travelling independently, but we all came together one night and they were all completely relaxed, chilled, hanging loose, enjoying the ride. And I thought in that moment, ‘f••king hell, I’ve ridden all this way, full of impatience, emotion, running, riding 33,000 miles from Sydney to London, New York to Alaska, on a mission and it’s only now I’ve got to the end that I’ve seen now how it should be done! This is how I want to do it, I want to do it how these guys are doing it, I want to enjoy the scenery, I want to chill out, to catch a fish even, spend a few nights at a campsite rather than hurrying on – none of that ‘I’ve got to get to the next destination’.

“‘Pull the clutch in.’ That’s how I can best express it. I’ve not done that. Just shut off, pull the clutch in, let things calm down, go quiet, find a better pace. I rode all across America and it was literally at the last destination that it all became clear. I had actually planned to ride further, but having found the answer I stopped there. I simply ended the trip right there. That was kind of it, I’d found what I needed.

“And after that I needed to write the next book, because I’d learnt so much about love, human existence, about things everyone goes through, because everyone is chasing a dream of some kind. I felt the need to write the book to help make sense of it. I made sense of some of it on the road, but when you come back and sit with your thoughts you can unpick it, make more sense of it, it’s self indulgent perhaps, but without it what you’ve done is senseless, it’s just a photo. If you can sit and write about it, make sense of it, it becomes understanding.

“If I do another trip I know what it’s all about – I’ve got it now. I know what it means, what it doesn’t mean, what it achieves, what it doesn’t achieve, and I’ll get more out of it.”

SO WHAT NEXT?

We shouldn’t ask, but we can’t help ourselves – what happens next? For now there is no answer. Nathan has filled the time since his American trip (ridden in 2012) working in journalism – a regular day job – and completing his second book. He’s self-published this book, but in the most professional manner – his Masters in business clearly hasn’t gone to waste. He’s also been savvy enough to use crowd funding to part-fund the project – but only at the very end of the process (after the book had already gone to the printers) and only after he’d sunk most of his own money into it. Having negotiated back the publishing rights to his (much acclaimed) first book he’s reprinted that too. And he’s dug deeper still, buying a stand at the NEC Motorcycle Live show to sell his books. There’s a sense with his second book he’s drawing a line under his travels, his experiences, maybe even his depressions.

“You know, so many of the bigger adventure rides start not through normal rational planning, but as a reaction to an event, maybe a cataclysmic event. Mine certainly did, but many others are the same. Maybe it takes that to make it happen.”

Discovery and understanding have quelled Nathan’s anger, his energies, he’s found some calm, some acceptance. And that may be enough, as he alludes to at the end of ‘Running Towards the Light’:

I look at her (his postie bike) and wonder if she has any adventures left in her, and I’m not so sure she has. Then I look at me, and ask, do I have any adventures left in me. And again, I’m not so sure I have.

THE BOOKS

Nathan’s writing is fresh, honest and spiced with wit – and as you can imagine his books are not mere travelogues. His reprint of ‘Going Postal’, as ‘The Long Ride Home’ won the 2012 Overland Travel Book of the Year (ahead of no less an author than Ted Simon). He is, in our opinion, recommended reading.

To buy copies of his books contact Nathan via his website www.thepostman.org.uk