The Dakar Rally is celebrating its 40th edition in 2018. So we’ve rolled back the years to the very first, to see where – and on what – it all began.

B ack in the late 1970s the desert rallying scene was in its infancy, and it was then a very French thing. For the French it was a very natural adventurous step to cross the Mediterranean and venture into their (former) African colonies. They’d been doing it for decades, informally. But in the late 1970s the concept of the adventurous race really came alive. The idea of a 10,000km stagerace across the deserts of Northern Africa certainly caught the French imagination. That rallying was still an adventure, more than a race, can be seen by the hotch-potch entry for that first Dakar Rally back in 1979 (nearly entirely privateers), which included a fair range of romantics peppered among the racers, including a chain-smoking journalist on a BMW R65 complete with screen and panniers, another hopeful on nothing more than a Honda XL125S, not to mention the usual array of humble Renault 4 and Peugeot 504 runabouts in the car class – there was even a Ford Transit. The first winner, overall and moto class, was a 23-year-old Frenchman, a former French trials champion, Cyril Neveu. He later spoke of that first Dakar not in terms of the competition but the adventure: “It was more a human adventure than anything else. It was a challenge that was to discover Africa first of all, by the motorcycle, and by means of competition. “So there were several challenges at the end, the discovery of a continent that I did not know, that fascinated me and after that the challenge of a victory since I came from a sporting environment.” That’s not to say the very first Dakar rally wasn’t competitive. At the front of the pack was the very first works rally team, Sonauto Yamaha, who bought an array of fast racers, some from motocross, some from trials. They were all riding Yamaha’s popular trail bike of the day, the XT500.

DAKAR’S ONLY PRIVATEER WIN The team, led by Yamaha boss Jean Claude Olivier was expected to win. But their tactics were their undoing. They rode fast and they rode together. When one made a navigational error, they all did and this happened as early as the third stage, when they lost five hours on the stage and lost a further seven hours in penalties. Subsequent fast riding did nothing to pull back their disadvantage, instead it ended in big crashes that sidelined two of their top riders, Olivier and Rudy Positek. Eventually, teammate Gilles Comte placed a Sonauto XT on the second step of the podium in Dakar – by means of steady work. He’d punctured and lost much time on the very first stage and so hadn’t ridden with the fast-n-furious Sonauto pack. He didn’t ascribe to the speed tactic, like Neveu for him it was technical skills and longhaul strategy that worked. Neveu won without taking a single stage victory, instead using technical ability and a long-game approach. And with the constant and valuable assistance of his father who could be reliably found at every bivouac, he had excellent support. And no doubt Papa Neveu was very useful when it came to an engine swap after the eighth stage. 1979 was the first and last time the Dakar was one by a private entrant. By 1980 Neveu (who would win five Dakars in all) would be factory-supported and he’s thanked his good fortune that happened as in his words ‘it allowed me to make my passion my job’. But the rally for Neveu has always been more than just a race: ‘For me, it is a fantastic life experience. I have not studied extensively, so it is a fantastic school of life. A school of humility because when one is alone in the desert with his motorcycle, one must know how to control the elements, manage oneself or even manage a team also because when one is part of a team, one has ‘accounts’. But it was only fun. And when you have the chance to live for thirty years your passion, it’s great.’

THE 1979 YAMAHA XT500 In the early 1970s there were no rally bikes, no adventure bikes. The Americans had enduros and desert racers. The Europeans simply had trail bikes. The XT500 accordingly responded to American demand, where dirt biking was booming and riders who’d enjoyed Yamaha’s cool reliable two-stroke DT trail bikes were wanting for something bigger. The XT was only Yamaha’s second four-stroke. Shiro Nakamura, leader of the XT engine project remembers:

“When the off-road market started booming in the US, bikers remembered the advantages of the good old singles. Soon the sales guys started to request the development of a four-stroke for off-road. Honestly speaking, we engineers were quite reluctant in the beginning, since we knew about the difficulties of these big thumpers. As soon as they had a bit more power they turned out to be unreliable and they were shaking like hell. “I can confess that developing this first big single was a real nightmare. We tested many different configurations including DOHC and even cylinder head oil cooling, but the XT was supposed to be simple and reliable and eventually we turned away from all these complicated solutions.

“In the end all our technical problems delayed the roll out by more than one year. But we had succeeded, the XT was now more reliable than a big single four-stroke had ever been! Although it was over-square with a bore and stroke of 87 x 84mm, (all British bikes were long stroke), we obtained the real character of a big thumper. The two-valve head gave a flat torque curve while the smaller flywheel allowed the engine to rev up as easily as we wanted. Dry sump and short stroke also allowed for better ground clearance and a more compact engine than former British bikes ever had.” The XT produced 32hp, in a package that weight 149kg (not light!), although it was simple in design. And Yamaha gave it traditional 21/18” wheels while the suspension was of the longer-travel type that was emerging. The competition-biased TT version was a hit in the US while the XT went big in Europe, especially in France, selling a reported 62,000 units there over its five-year lifespan. The bike was then ideally placed when the rally phenomenon took off. As well, with Yamaha having a well developed motocross range, with components that could crossover to the XT, it was possible to create a competitive rally with parts straight off the parts shelf.

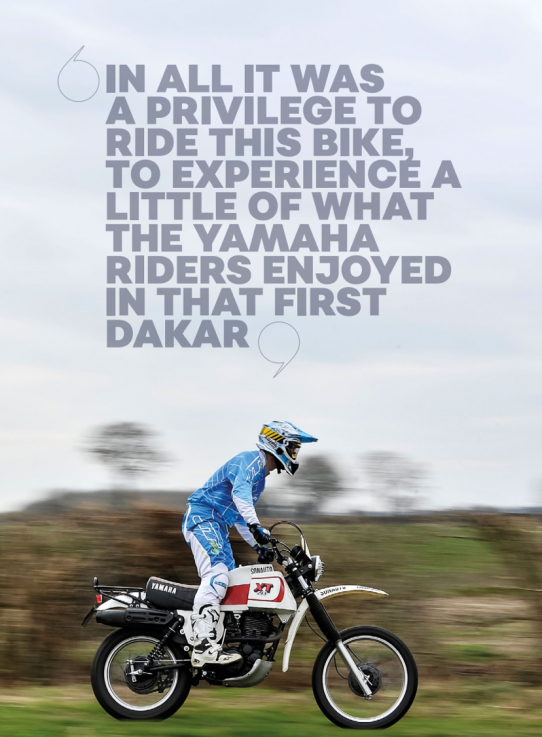

RIDING THE SONAUTO YAMAHA XT500 (REPLICA)

This isn’t Christian Thayer’s Sonauto Yamaha XT500 from the 1979 Dakar. But it’s so close to the original even Thayer himself was apparently close to believing it was the real thing. It’s been painstakingly researched and built by an XT500 enthusiast based in the UK’s Lincolnshire. Mark Smith has restored countless XT’s before this, but fancied a bigger challenge. And it was a bigger challenge, for as Smith explained, he had little more than photos and the odd French Dakar-fan website to reference. As a consequence so many of the parts were recreated from scratch, simply scaling from old photos. Some aspects of the original bike’s build he could trace fairly accurately, like the use of the YZ400 forks and rear wheel. Other things, like the unique rear brake arrangement, he

had to work out for himself, probably, Smith says, much like the Sonauto mechanic did back in the day – cut this, weld that. And as these were the early days of rally, the suppliers back then weren’t the specialist suppliers you’ll encounter today. So that original super-padded Dakar seat, it was made by a French slipper manufacturer (Smith: ‘actually my seat isn’t the same, the original was leather on top and plastic on the sides, it looked ghastly, so I’ve used suede on mine!’) And some things you simply can’t source today, like the rear shocks. Smith thinks the Dakar bikes ran 400mm units (Konis in later years), but he can’t find similar today, so the 360mm units he has are the nearest he could find. It is though a triumph. The attention to detail means, save for those shocks, everything is ultra-close to the original, right down to the handmade racks to support the tool bags on the back mudguard (a period Preston Petty, of

course). It really is a time warp experience. The simplicity of the XT, the robustness, puts you more in mind of a WWII bomber than a modern day rally racer. It speaks of the end of the analogue era. And yet the XT feels surprisingly muscular. It felt like that back in 1976, too. Some 32hp was pretty lusty for a 500cc single back then. But I’m surprised it still feels so punchy today, when we’re used to seeing nearly 60hp from a 500. The XT should feel ‘pony’, but it doesn’t. You can attribute that to the fact that the 32hp is at least well-concentrated, for that power all comes in the first 6000rpm, or thereabouts. Modern 500s will rev to around 9000rpm, and more, to unleash their full potential, so there’s a sense of the power curve being stretched out. With the XT it comes in early and with meaning. Okay, it’s not quite arm stretching, but certainly enough to make your butt sink back into the soft foam of the

luxuriant saddle as you wind on the throttle – and with a slight tug on the handlebars that makes for easy, almost slow-motion, wheelies. And while 32hp doesn’t sound much, there’s a feeling that this much does at least exceed the capability of the chassis, for ridden offroad that comparatively basic spec suspension soon feels to be both bottoming and topping out – suspension tech still had a long road (track) ahead back in 1979. Yet the XT is hugely enjoyable. It needs a kick to start, by the way. There are tales of legend about kick-starting XTs, but with this example it couldn’t be easier. Just gently turn the engine over on the kick start until the compression stops the process, then pull in the compression release lever and with a gentle push on the kick start gently push the engine just over top dead centre, then release the lever and give the kick start (from the top of its arc) a firm swing, on zero throttle. The XT fired

first time every time. Maybe those old XTs just needed a good fettle; with a clean set of points and a well setup carb it’s no issue. Or maybe we just got lucky. There’s a five-speed gearbox in the XT, which shifts surprisingly sweetly, up and down, and given the low rev excellence you’re not fishing for a sixth ratio. This XT had slightly longer gearing, ideal for desert racing, so it would cruise at 50mph with just a gentle throb from the motor. We just loved the Dakar modifications, they make the XT even more special, and although this is a replica, it’s so faithful to the original (these are the correct 400MX forks, it is a TT-spec exhaust, every detail has been meticulously recreated) that the performance feels utterly authentic. The XT rides high on the Dakar suspension set-up and the special seat adds further to the height, so you ride at a similar height to a modern bike, it’s not arse-dragging low. And while us modern day riders struggle to adapt to the seated riding position – the generously swept-back handlebars ensure you do stay seated (to stand when riding was clearly considered no more than an emergency procedure back then) – to be seated feels surprisingly natural on the XT. Besides the tank is so wide at the back (let alone at the front!) that standing requires a slightly bow-legged gait. Sitting is the correct modus. In all it was a privilege to ride this bike, for just a short while to experience a little of what the Sonatuo Yamaha riders, and indeed Cyril Neveu, enjoyed in that first Dakar in 1979. For sure, inside of a decade, desert race bike development would bring sophisticated machines that make the XT look like a kiddy plaything, but that still can’t diminish what a superb bike the Dakar XT was, nor its significance. Some 38 of the 90 bike entries in that first Dakar were XT500s. And for a while there the XT was to rally what Yamaha’s TZ was to grand prix road racing. Respect is due.