Rust Sports brought together a relatively modern KTM 350EXC with its 1993 equivalent and went for a ride to find out what many years of development has done for the marque…

It’s funny, you really don’t tend to notice the tiny incremental changes that happen year on year. And it’s only when those changes are taken together – for instance when you try squeezing into a pair of your old riding jeans for a photoshoot with a 20yr old bike – that you notice the much BIGGER changes that have crept up on you over the years…

KTM’s 350EXC is a bit like that… the 350cc enduro capacity is not a new concept as evidenced by this 1993 350E-XC (note the extra dash in the name). But as anyone who has ridden one of the newer machines will tell you, it’s now a much more exciting and appealing prospect than ever before.

I can remember testing bikes like the old 350E-XC we have here, and feeling pretty underwhelmed by the whole experience. Sure, it was a pleasant enough machine, but it was never going to set the dirt bike world on fire in the way that the latest version has. So what’s changed in the intervening period, to make all the difference?

Well we thought it would be fun to get a 20yr old 350E-XC and its modern day counterpart together, to consider how far we’ve come in the last 20 years. Not as a comparison test – everyone knows the modern bike is way quicker than its forebears – but as a way of illustrating just where those incremental changes have led us…

Rev it Up!

Let’s get straight to the point shall we… the biggest single difference between these two bikes (and the greatest single development that has improved all dirt bikes during the past 20 years) is in terms of the power they produce. For any given capacity, there has been anything up to a 50% improvement in the power available. The 1993 350 was probably producing about 25hp (at the rear wheel), whereas the latest bike makes more like 38! That is a huge increase in efficiency, and interestingly KTM can’t claim credit for that at all.

Yamaha started the ball rolling back in 1997 with their ultra-high revving, short-stroked, twin-cam YZ-M400F works motocrosser (and subsequent YZ-F and WR-F machinery), which paved the way for a whole new generation of powerful thumpers. And whilst manufacturers like Husqvarna, Husaberg AND KTM, were already building what were considered back then quite revvy machinery for the time, the Yamaha simply tore-up the rule book and forced them to think again.

Ultra-short-skirted pistons boasting huge bore areas and tiny strokes, allowed engines to rev on into the stratosphere. All of a sudden undreamt-of power was available – albeit at a cost, in terms of piston life and frequency of rebuilds. Overnight, four-stroke pistons, con-rods and camchains became service items, and the engines they were fitted in required stripping and rebuilding as frequently as those of their two-stroke counterparts.

Twin-cam cylinder heads became the norm (at least from the Japanese manufacturers), and that in turn allowed smaller, lighter valve-trains to operate at much higher speeds, pushing up rev-limits and horsepower. And although KTM persevered with SOHC designs for much of the past 20 years (principally in order to improve rideability), their modern 350EXC has seen a switch to a twin-cam layout that’s allowed them to extract significantly more horsepower from a 350 displacement and ultimately to re-invigorate the 350 ‘class’.

Fuel-injection has helped of course. A modern EFI set-up allows the latest machinery to precisely regulate the amount of fuel delivered at any given RPM, whereas the old bike – fitted with a rudimentary Dell’Orto carburettor – was a bit hit-and-miss at the best of times. [And as an aside it also means the modern bike has a much lighter throttle]. Couple that switch (to more precise fuel delivery) with clever electronics that allow you to change between ignition curves at the flick of a switch; and it’s easy to see how engines have become much more efficient (at extracting power from fuel) over the past 20-odd years.

Weighting Game

Unlike the Rust Sports waistband of course, progress in terms of dirt bikes has been towards smaller, lighter and slimmer designs, with the aim being to produce a sub-100kg motorcycle. A heavier bike is a slower bike – for obvious reasons – but looking at these two machines back to back, it’s not immediately obvious where the significant weight savings have been made.

Both use a traditional cro-moly steel frame, both have similar sorts of suspension, wheels and other cycle parts, and both carry roughly equal amounts of fuel. The answer of course is in the engines where a steady process of miniaturisation has been continuing unabated since the Japanese (yep, it’s them again), started it off back in the late ‘60s.

Up until then, motorcycle engines had been large, lumbering chunks of semi-agricultural machinery with very little attention paid to weight saving. But the Japanese changed all that… Using lightweight alloys that quickly dispersed heat, they begin building smaller and lighter powerplants, redesigning and more importantly, re-packaging all the vital components into a smaller space. This is a process that KTM has picked up on and used very successfully for its own machinery – and is very much in evidence in these two bikes.

Improvements in materials have led to much smaller, lighter crankcases housing lighter crankshafts (thanks to lightweight pistons), and that in turn has allowed every other aspect of the motor to be minimalised.

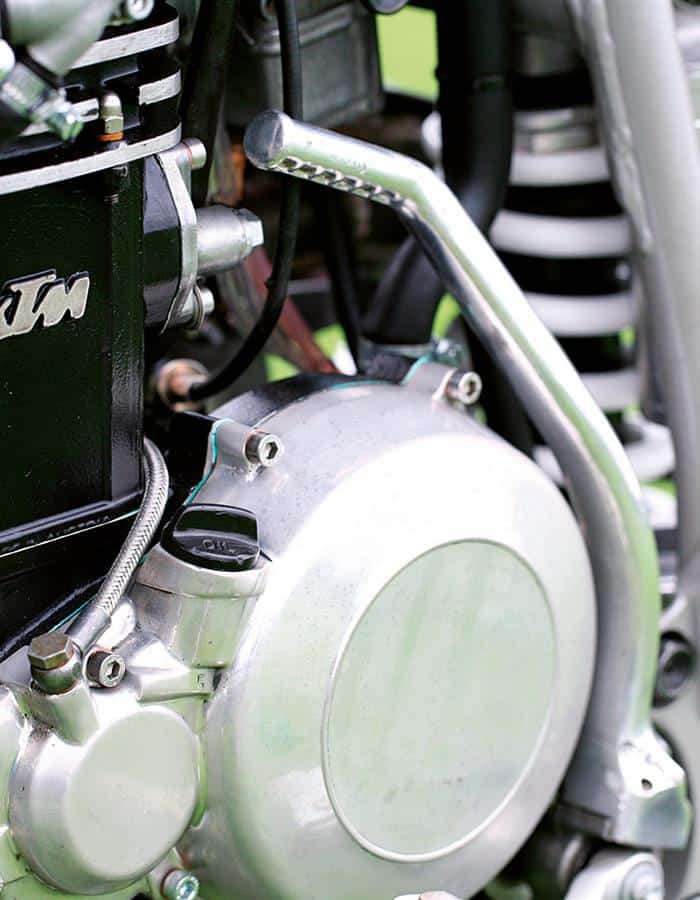

Look at these two engines and you can see the physical reduction in size that has taken place during the past 20 years – despite both of them displacing the same capacity. Is there much scope for further improvement? Definitely, as engines continue to extract more power from fuel, so the physical dimensions are likely to shrink as we move towards ever-smaller capacities.

Of course it’s not just in the engines where progress has been made. Improvements in design and materials has allowed for a certain amount of weight savings to be made in items like frame design, swingarms, suspension (no linkage on the new 350), radiators, fork and shock bodies, digital instruments, brake components, hollow axles, lighter seats, alloy sidestand (rather than a steel centrestand) and even lighter-weight plastics, wheels and tyres! In fact virtually every component of the bike has been improved in the intervening double decade.

Collectively they add up to about a 15-20kg difference between these two machines, and when taken with the improvements in specific output, significantly improve the machine’s power-to-weight ratio.

Sit on It

Look at the two bikes facing each other in the opening picture and the progress in terms of riding position is immediately apparent. The latest bike has a much flatter seat with a more forward-mounted riding position, whereas the older one has a much more curved seat that places you ‘in’ the machine, and behind the fuel tank. And you really notice this when you climb aboard and start riding.

The modern bike’s fuel tank is much narrower up top and combined with a firmer, slimmer seat, enables you to move about more easily on the machine. This has a huge affect on the bike’s handling, and is not just preferable – it’s absolutely essential on a modern bike like the new 350EXC.

Without the ability to get forward over the bars, you would simply wheelie off the back virtually every time you opened the throttle. And likewise improvements in terms of braking efficiency – together with much sharper steering geometry – means that you now need to be able to get much further back on the bike in order to prevent yourself disappearing over the bars whenever you pull on the front brake.

This is one area where you can immediately feel the difference between these two. Older bikes have broad seats (and splayed plastics) at the rear of the machine, whereas it’s noticeable now that manufacturers are paying much more attention to the width of the seat, subframe, plastics and exhaust at this part of the bike, in order to facilitate easier movement by the rider.

By contrast the older generation bike has you sat much more in the middle of the machine with your knees splayed around the tank and your feet resting on narrower pegs. And whilst you can still move forwards and backwards to a lesser degree, it’s nowhere near as easy (nor as essential) in order to get the bike to perform to its max.

One further point I would make on this is that flat seat designs are not a new phenomenon. Plenty of dirt bikes from the early Nineties sported a similar sort of look to the modern-day KTM (Yamaha’s WR200 for instance). But what has changed is the height of the top of the fuel tank. A reduction in the overall size of the engine has allowed manufacturers to steadily lower the height of the frame’s backbone so that the fuel tank now sits lower and the seat is flatter.

And if you look closely at the respective shape of the steel frames on these bikes, you can see that whereas the old 350’s frame has an angular change of direction around about its middle, the modern bike’s frame rails are much straighter and lower. That’s progress…

Start me Up!

Did I forget to mention that as well as shedding weight, the modern day bike has even managed to incorporate a heavy starter motor and battery for its push-button starting convenience. Contrast this with the older bike’s starting procedure… Turn on fuel. Operate choke or hot-start (depending upon engine temperature). Swing out (annoying left-sided) kickstart. Pull in decompressor lever. Ease over top-dead-centre. Release compression lever. Return kickstart to top of stroke. Kick, hard, remembering not to crack open throttle until engine catches. Depending upon success, repeat procedure. Don’t forget to flick kickstart-lever back in, and switch off choke/hot-start, or you will be doing it all over again very shortly.

Look, you don’t need me to point out that the electric-starter is as essential a part of the modern four-stroke dirt bike as the kill-switch, and anyone who argues otherwise is stuck in a time-warp. People have campaigned for years for manufacturers to equip their bikes with electric-starters and in fairness KTM were one of the earliest adopters of the technology. And have gone on to debut it in MX and on two-strokes. It’s obvious really… we all want to spend our time riding our dirt bikes, not kicking them half to death!

Starting the old 1993 E-XC was a painful reminder of just how tiresome the process was back then. And although this one started fairly easily and idled away happily, it’s an entirely different prospect when you’re stuck part-way up a tough climb, buried in a bog and can’t get a swing at the starter, or just plain knackered!

Ride on Time!

Although we only took a brief ride on both machines, it was sufficient to realise that 20 years is a helluva’ long time in terms of dynamics and performance. Funnily enough I really loved the sound the old engine made when it was being revved hard. It was a glorious high-pitched roar that sounded like an old Sixties racing car – the sort of noise a good racing engine ought to make. But for all the gorgeous sound it produced, this never really translated into forward progress.

For certain there’s a lovely seamless power from the ‘93’s motor that builds and builds without ever reaching any kind of crescendo. Sometimes you find yourself with the throttle wound fully open waiting for the revs to catch-up. Other times you just find yourself wondering what you’re having for dinner that night, and wishing mealtime would arrive sooner. It’s quite charming in a non-threatening way and I definitely enjoyed reliving the experience. But for sheer blood-n-guts in-your-face aggression, nothing can touch the new machine.

It has that instant ‘oh-my-god-I-can’t-quite-believe-this-is-happening’ type power delivery that comes in nicely at the bottom, kicks quite hard in the midrange, and then threatens to tear off your arms and slap you with the soggy ends, right at the top. There’s power, revs, torque, revs, acceleration, wheelspin, revs and finally more power. And the smile it puts on your face takes an age to disappear.

Cost of Living

And that’s really the bottom line here. Because the biggest single improvement we have seen in dirt bikes over the past 20 years is the amount of fun they deliver for the money. In the intervening two decades dirt bikes have got faster, more powerful, quieter, lighter, easier to start, easier to stop, have improved in quality, improved in handling and in real terms (taking inflation into account) they are getting cheaper to buy every year Yes, really! In terms of bang-for-your-buck that makes them better value now than ever, with simply amazing performance available from a humble 350cc.

And you know what…? I’m glad, because as I found out when I went to get changed into my old riding kit, clearly I’m not getting any smaller…

There are many more issues of RUST Magazine for your perusal just click on the link for the full list and enjoy! https://rustsports.com/issues/