Here at RUST we tend to gravitate towards machines which were different for different’s sake, but Husaberg’s 70-degree four-stroke is one innovative design that really did work. And here’s why you should buy one and what you need to know if you do…

It caused a sensation when it was launched, and that feeling continued when you actually rode one. Turning the engine architecture topsy-turvy resulted in a bike which handled far better than any other production thumper, whilst Husaberg carefully retained fantastic ‘enduro-style’ power. And that, in a nutshell, is why you want one. Unfortunately, the bikes were only in production for four years – 2009 model year to 2012 – as KTM rationalised their engine production and gave Husaberg EXC engines to use from 2013-on. So now’s the time to buy. Because, as the cliché goes, they’re not building any more!

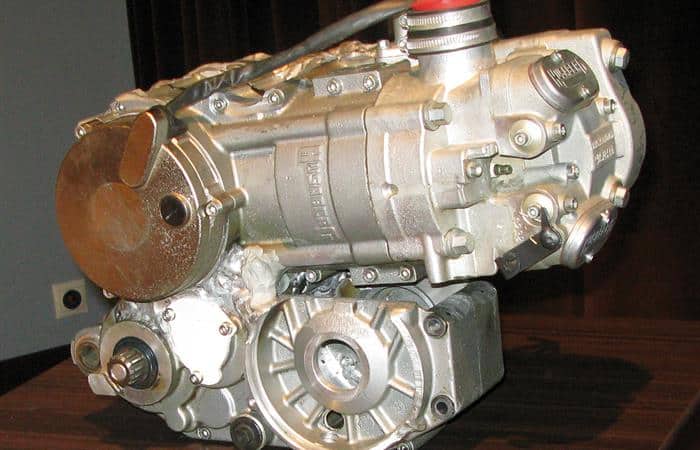

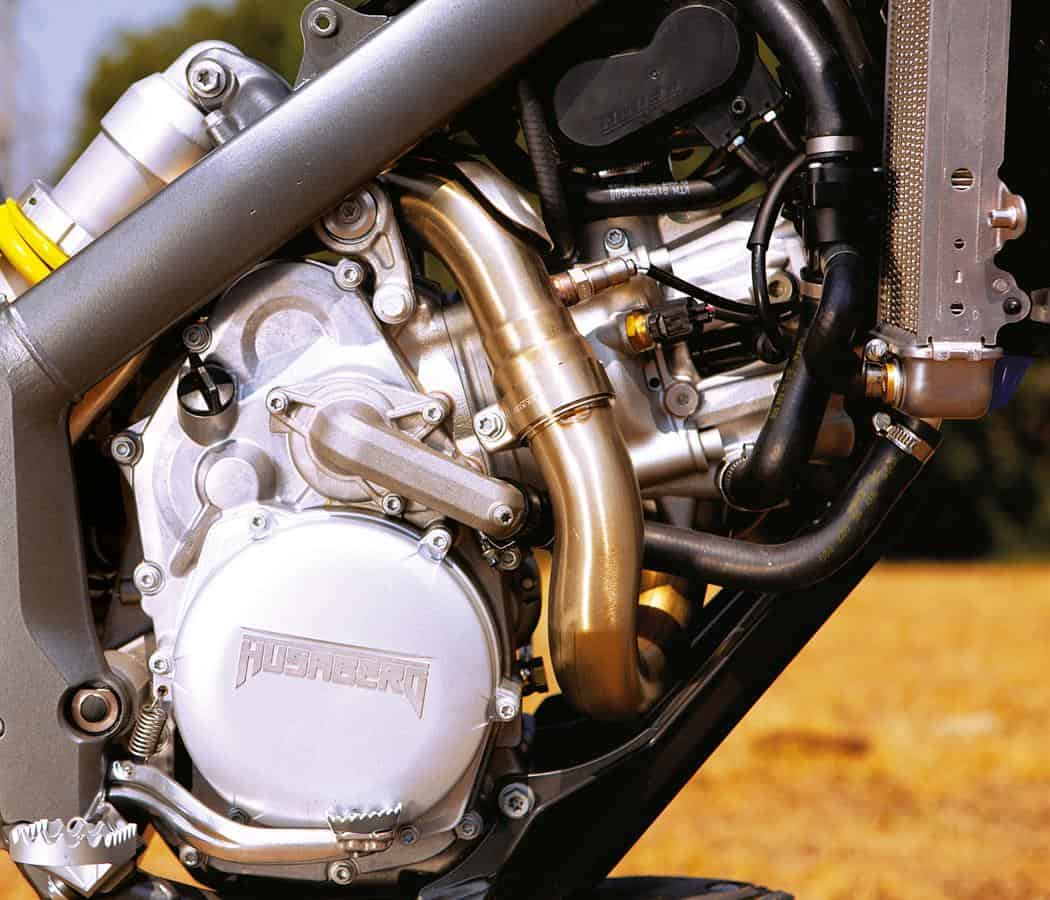

Below: The FE450e, seen here in SM format. Bottom right: The original FE650e in enduro form with the ‘2T bottom end mated to a 4T top end’. However, it worked! Below top: The original test-bed engine used when developing the 70degree motor.

Early Days

The previous SOHC Husaberg engine design had remained incredibly similar to their original motor, dating way back to 1989. Basic, to the point that it was often described as ‘a 2T bottom-end matched to a 4T head’, it nonetheless produced good, enduro-style, power and, in the case of the 650s, good power full stop!

In terms of rideability, it remained a fine engine. The 450 made fantastic, easy-to-use, grip-finding, enduro power, and when sleeved down to 380cc it became thrashable too. And the 650 engine found favour with club SM racers the world over.

The problem was marketability. Husaberg had a reputation as something of an off-the-wall choice, and the fact that their engine looked incredibly dated didn’t help it sell against the new breed of four-strokes. Despite many of the engine’s mechanical issues having long-since been sorted, this visual similarity with the older motors didn’t help the brand to shake its reputation for unreliability, either. Something needed to be done. And how the 70-degree engine came about is almost as shocking as those very first glimpses of it back in 2008…

The Engine

Rotating mass and its gyroscopic effect. That’s what’s behind the engine’s layout. The Husaberg technicians looked at the conventional four-stroke engine and questioned how they lessen the effect of the crankshaft’s rotating mass. After all, a crank is a hefty lump of metal, spinning at anything up to 13,500rpm in a modern production single. Sure, you could reduce its weight, but by doing so you’d also lose tractability and eventually you’d be left with a superlight engine that was TOO quick revving for an off-road application.

Instead, they thought about moving the mass and locating it closer to the bike’s Centre of Gravity (which is generally behind the cylinder, just above the gearbox).

Having mentally run through the repercussions of relocating various major components there was nothing else for it but to see if the design would work. And rather than tool-up for an expensive prototype they chopped-up a couple of their existing engines, moved everything around until it was where they wanted it, and then bolted, welded and epoxy metalled the Franken-motor back together.

This test donk looked like a jigsaw with the pieces wedged in the wrong place. It also had no oil circuit, so was effectively lubricated by what oil they coated the components with when they assembled it… and of that what didn’t leak out from numerous ill-fitting mating surfaces.

The motor was installed in the existing Husaberg frame and given to factory rider, Joakim Ljunggren, to test around a twisting special test. To get near the times he set on his existing racer would’ve been impressive. To go quicker, and have Joakim find the bike easier to ride, was phenomenal. So to confirm that this wasn’t a fluke they moved to a new venue. The result was much the same…

Without these findings you’ve got to wonder whether Austria would’ve funded the development of such an unconventional-looking lump. But fund it they did, and the Swedes went off to refine their design.

As raising the crank (100mm higher and 160mm further back than ‘normal’) in turn raised the C-of-G a touch, they countered this shift by angling the cylinder forward at 70-degrees.

As well as lowering the C-of-G, laying-down the barrel also allows for an incredibly straight, downdraft, inlet tract. The Keihin fuel injection’s throttle body could now effectively sit ON the cylinder head rather than clinging onto the side of it like on a traditional motor, and atop this they could mount the air filter – thus retaining Husaberg’s traditional ‘under the front of the seat’ location, the water-fording abilities it allows, and the ‘honking’ i nduction noise which sounds like you’ve trapped an irate goose under the tank!

The result is a machine with a higher C-of-G than a conventional dirtbike, though with the rotating mass far closer to this point. And with a SOHC, four-valve, top-end and a bottom-end which maintains that all-important crank weight, it should still produce enduro-friendly power yet handle better than its peers.

A kickstart wasn’t factored into the equation. Whether they reasoned that battery and starter technology was such that it wasn’t really required, or whether the weight penalty (and engineering issues) it brings were prohibitive, Husaberg wouldn’t say.

As with most European enduro bikes, a six-speed gearbox was considered de rigeur, and Husaberg complemented this with a clutch assembly featuring rubber dampers. The theory is similar to that of a cushdrive in a rear hub, the rubber taking some of the shock out of the drivetrain, thereby reducing stress on components and giving a smoother feel. Clutch operation is, naturally, hydraulic.

First built as a 450 (449.3cc) and 570 (bored and stroked from the 450’s dimensions to give 565.5cc), the following year Husaberg released the 390 (393.3cc). This drop in displacement was achieved not, as you might think, by simply sleeving the 450s barrel, but instead with a new shorter stroke, heavier, crank (and longer conrod to match). The compression ratio was dropped a touch too.

The Chassis

Previously, Husaberg were renowned for being incredibly lightweight, something that was visually reinforced by their airbox-less design, with a gap in the subframe where the filter would traditionally sit. Whilst the 70-degree models retained a similar air filter location (under the front of the seat), the space in the self-supporting plastic subframe was filled with part of the three-section fuel tank (though not plumbed in) and, indeed, the bikes’ visual weight-gain was backed-up by the scales. Indeed, it was now parent company KTM whose bikes were routinely awarded the rosette for ‘lightest in class’ whilst the Bergs were a few kilos heavier than their orange brethren – though still lighter than the Japanese offerings.

A steel perimeter frame held everything together, with the air filter nestling between the top tubes rather than using the frame as an airbox, as on the earlier machines. The downtubes curve around the front of the motor, the engine architecture allowing for some impressive ground clearance.

WP forks, PDS shock and Brembo brakes will be familiar to most, and anyone who’s seen a modern KTM will recognise the clocks, switchgear, footpegs and various other ancillaries. The riding position is similar to its orange counterparts too, eschewing the long ‘n’ low feel of Bergs of old for a taller, more aggressive stance.

Aesthetically, the engine obviously caused a bit of a stir and the whole bike was sufficiently different from its contemporaries to be distinctly ‘Husaberg’. And we like it. A lot.

The Ride

Husaberg may have redesigned the four-stroke engine but you don’t have to reconfigure your riding style. They ride like a VERY nimble four-stroke which doesn’t push the front-end as much as we’ve come to expect from off-road thumpers.

No matter which model you choose, the Berg is blessed with an incredibly responsive throttle. Coming from a carb’d bike it can take some getting used to, and once you do you’ll find that it allows you to exploit the grunty powerplant. Likewise, the beautifully slick gearbox makes the whole experience incredibly efficient and, quite frankly, an utter joy!

We’ve never found cause for complaint in any of the bikes’ suspension set-ups, though naturally this is down to personal preference. Technologically-speaking, the closed cartridge forks on the later bikes are the ones to go for, though don’t feel you’re missing out if you can only stretch to an early bike with regular 48mm WP legs. They’re still excellent.

The PDS shock works very well, and the lack of linkage means increased ground clearance and fewer bearings to replace. As with any bike, you simply want to ensure that everything’s set-up to suit your tastes and weight.

FE390

Gruntier than a 350EXC-F, with a lovely light demeanour, the 390’s an absolute gem of an allrounder. Husaberg claimed that the bike was aimed at the hobby rider who wasn’t constrained by traditional capacity classes, or for those racers who entered a lot of endurance (six hours plus) or extreme events, where a smaller, easier-handling bike would be beneficial. And they got it bang on!

Plusher suspension and a heavier crank than the other models mean its incredibly tractable and on the trail the torque makes it incredibly efficient, allowing you to worry less about gear selection and more about the terrain. There’s still enough power to keep up with big bikes on open going, and on singletrack it jinks around trees with minimal effort. More than that, the front-end is so millimetre-precise that it inspires a huge degree of confidence. Mountain goat tracks hold no fear…

For racing, it shoved you out of turns whilst 250 4Ts (and again, the 350 KTM) were building revs and waiting for the power to kick-in.

Did the engine design make it feel as small as a 250? Well, not quite, though it was noticeably lighter-handling and FAR easier than a 450 to ride for long periods of time.

FE450

The 450 comes with a very healthy bottom-end and enough up top to hang with pretty much any other E2 machine, though it’s again the nimble handling which really makes the FE stand out. The very sharp throttle response demands fine control, and with instantaneous access to that chunk of low-to-mid range torque this may not suit everyone’s style or tastes. The KTM of the time featured a far smoother power delivery, and ultimately made more at the top-end too. But it was out-handled by the Berg…

FE570

Arguably the easiest ride in the E3 four-stroke class – despite featuring the biggest displacement – the 570 produces a broad spread of power which allows you to cultivate an incredibly lazy riding style. Well, you weren’t thinking of going enduro racing on one, were you?

Great in a straight line, nimble when you need it to be; the 570 is a wonderful machine for the kind of open trails you see in the south-west or on the Continent…

FX450

The FX is the stripped-down, Cross Country racer in the line-up, and was introduced for the 2010 model year. The biggest difference between it and the enduro FE was probably the gearbox, which was given a taller, more MXey first gear, followed by closer ratio second through to sixth. Visually, the first thing you’d notice is the lack of lighting, and any other road accoutrements. Thankfully, they retained the quiet enduro silencer.

Closed cartridge forks were standard fitment right off the bat, and the suspension was set-up that little bit firmer than the enduro models. A lower (than on the enduro models) set of Renthals bars gave a more MXey feel to the experience, and the engine was just that little bit more eager than its FE stablemate.

As an XC racer it’s a fantastic ride, as it’s that bit easier to get to grips with than a converted MXer or even KTM’s 350+cc XC-Fs yet still has great performance. Swapping the 19in rear wheel for an 18in enduro rim would open up a greater range of events, mind you…

FS570

The FS supermoto was another new Berg launched for 2010, and followed in the wheel tracks of the incredibly popular FS650. The previous year Husaberg had filled the 17in (rim) gap in their range by offering a supermoto ‘kit’ (smaller wheels, bigger brake disc etc) for their enduro bike but the FS was the real deal.

The brake caliper was a radially-mounted, four-piston Magura which gave a considerable boost in stopping power over a two-pot unit hung from a spacer bracket. The WP suspension was SM-specific (shorter and firmer), and the triple clamps allowed you to adjust the offset, while the spoked rims were a special sealed design from Saxess which allowed you to run without inner tubes.

The neutral handling of the 650 made way for a far more ‘on it’ approach and the trademark super-smooth power remained. Had the supermoto scene not been on-the-slide then it could well have proved to be a decent seller. But as it is, the white/blue/yellow bikes are incredibly rare in the UK.

What Changed? And when?

2009: Launch of FE450/570.

2010: Due to the arrival of the FE390/FX450/FS570, there weren’t huge changes made for 2010. Inside the motor, the big-end bearings were given a DLC (Diamond-Like Carbon) coating for greater reliability… and that was about it for the powerplant. Chassis-wise, the bikes received the usual year-on-year suspension tweaks and the forks were now held in place by black-anodised clamps with a new offset (22mm from 19mm). The braking set-up received new Toyo pads and the routing of the front hose was improved with a new guide on the headlamp shroud. A new heavy duty DID chain was fitted, though arguably the most important change – certainly from an ownership point of view – was the fitment of a low fuel warning light!

2011: This was the year that Husaberg launched their two-stroke range and so, again, little changed on the existing four-strokes. Closed cartridge forks as standard was the big news, and the front-end saw further mods with a reinforced steering head (giving greater longitudinal stiffness) and Neken handlebars in exactly the same bend as the Maguras they replaced. New valve spring retainers, changes to the timing on the 390/570’s auto decompressor and a new material for the intake manifold were the only changes deemed necessary for the engine. Visually, predominantly blue plastics, plus a gentle reworking of the graphics, gave the 2011 bikes a SLIGHTLY different look. This was to be the last year for the FS and FX models.

2012: Yellow frames? Really? ‘Fraid so. For their final year, the 70-degree Bergs were proudly (and loudly) displaying their Swedish heritage by featuring even more of their country’s colours. Those more concerned with aesthetics than Swedish patriotism were glad that much of the custard-coloured frames were covered over by black frameguards! And speaking of guards, at long last all models came fitted with hand- and sumpguards as standard.

The fuel tank went from semi-translucent grey to what wed refer to as ‘clear’, making it much easier to check the fuel level on-the-fly.

What Goes Wrong With Them?

Being built to the same standards as a KTM means that the Bergs are inherently strong machines, and have moved away from their reputation of fragility. Quite the reverse, in fact, as the build quality and finishing is excellent, the engine has a reputation for being incredibly robust, and servicing jobs such as valve clearance checking aren’t a major issue for those with a little mechanical knowledge. Just follow the book to ensure you replace/clean all of the oil filters/screens. Air filter access is fantastic – simply pop the seat using the catch underneath, unfasten the sprung clip holding the filter and remove the foam element. It’s a doddle.

Of course, a few issue have arisen, though nothing TOO onerous…

The automatic camchain tensioner on 2009 models was known to fail (KTMs had the same issue) and the same problem can occur on high mileage bikes of any year. You’ll hear a distinct rattle if it’s giving up the ghost (something a seller will be hard pressed to mask) and unless you completely ignore this ‘audible warning’ and ride the bike for a long while, with it sounding like you’re dragging an anchor chain behind you, it’s unlikely to do any damage before you get it sorted. Some owners swapped to an aftermarket unit rather than a replacement OEM part – it’s not a big job to fit a new one.

Nor is fitting a new seal to the output shaft (behind the front sprocket) should it start to leak. It’s not particularly common and it’s an easy problem to spot…

Some owners have reported the clutch giving problems when it gets very hot, such as when slipping it up a long ‘n’ tough hillclimb. The problem is most likely to do with a seal in the slave cylinder master cylinder, or the hydraulic fluid itself (which is well worth checking/replacing from time to time)

Should the fork seals start to weep then the hot ticket is to fit SKF parts intended for a 2012-on machine. These are low friction items which are reported to give a much-improved fork action, as well as increased seal life. You’ll know if they’re the right ones because both the oil seal and the outer dust seal are green in colour!

And while we’re talking seals, give the rubber gaiter on the sliding rear brake caliper a regular clean-out. Dirt on the slider can wear it oval, leading to the caliper sticking and increased pad wear. You’ll find the rear pads wear quite quickly anyhow, as there’s not much surface area to ‘em.

One issue that has presented itself via internet forums, which hasn’t been quite such an issue here in Blighty as in has in the States, is fuel pump failure. Blame seems to lay in the routing of the exhaust header pipe so close to the pump (in the bottom of the tank), and owners are suggesting that the pump is being damaged by the heat radiating from the pipe. In such cases the fuel filter is being clogged with minute pieces of the pump, so the bike starts to run badly long before the pump dies. However, no-one that we spoke to in the UK has come across this problem, so it could be that the low quality fetid slop they call ‘gas’ in the USA is to blame for any degradation.

As with any fuel injected bike, cleaning/replacing the fuel filter as part of the service regime and (if you fill the bike from a fuel can) using a funnel with a fine gauze in the spout should help keep it running sweet. If you remove the fuel tank pay close attention to the routing of the wires running beneath it. They shouldn’t snag on anything or be so taut as to put stress on themselves or any connections. Ensure that the clip at the rear of the tank isn’t rubbing on the loom.

Finally, make sure that your washing machine is in tip-top condition too. The rear fender on the Bergs is comparatively short, and we’ve heard from owners that when you get stuck in a mudhole you might find that the spinning rear wheel deposits roost on the back of the bike… and the back of your shirt…

What to Pay?

Back in 2009 a new FE450 would’ve set you back £6395, with the 570 £100 more. By 2012 those prices had risen to £6995 and £7095, respectively, and £6895 for a 390. The closed-course FX initially retailed for £6345, the supermoto FS £7395.

Unlike earlier Husabergs, this generation have held their money well and, unlike a Cypriot bank account, you needn’t worry about losing a large chunk of the money you invest in it…

When it comes to individual models, the value follows a similar pattern to the new bike prices. So a 390 will be worth rough £100-200 less than a 450. In years past, the 570 probably would’ve been the least desirable of all, only now it’s commanding something of a premium thanks to finding favour with hobby rally racers. Expect a decent one to be a few hundred quid more than an equivalent aged 450.

A similar story applies to the FS570. There’s not that many out there, and if you want one you can expect to pay reasonable money for it. Remember, they were well over seven grand new.

On any bike, accessories are good at tempting buyers and quality parts do add value. For example, an Akrapovic end can adds a couple of hundred quid over a bike wearing the standard silencer.

And the FX model? Well, they were the cheapest of all the bikes in the range, and given their lack of roadkit they had limited appeal. The 19in rim was off-putting too. All of which means that if you really want one then don’t pay over the odds for it. It’s worth a good deal less than a road registered FE, and bargain hard if it’s still wearing that MX-size rear rim!

Why you want one?

Because they’re a fantastic ride, that also looks very different to every other bike out there. The 70-degree Berg is almost certainly going to be a future classic, given the fact that it is a well-constructed example of innovative engineering, that sold in big enough numbers to have a decent following yet small enough to make them kinda exclusive.

It was a sad day when KTM opted to discontinue the engine in favour of giving Husaberg the EXC engines, not just because the bikes felt different to ride but also because it enriched the dirtbike market, furthered the technology within the off-road scene and underlined the brand’s off-the-wall approach. Perhaps Stefan Peirer will buy the design off Husaberg and use it in his new Husqvarnas..?

Thanks to:

• David at independent Husaberg specialists Taffmeisters 01353 723883 www.taffmeisters.co.uk

• Mark and Jason at Husaberg dealership The KTM Centre 01442 255272 www.thektmcentre.co.uk

2 responses

Sounds strange, when you cleaned the injector, did you open it, i.e. apply power to the leads? Was the spray pattern obvious when you sprayed injector cleaner though it? Has the air filter disintegrated as most do after a few years? That will make them run wierd. Is the air filter oiled correctly? Does it not accept throttle when warm? They warm up very quickly and headers will glow red in low light situations within minutes of idling. Also make sure high idle button (on left side of thottle body) is not out, many owners don’t know about it! Does it have the correct spark plug in it? are you running good quality minimum 95 octane fuel? Have valve clearances been checked? Tight valves will cause problems if it has lots of hours, don’t believe hour meter- it may have been disconnected! Hope I’ve given you some clues. These are generally fantastic motors.

Rik

Thanks for a very interesting read.

I have a few problems with my 2012 fe399.

It has very low use (2hours ).

I bought fro. Original owner who had used it once 7 years ago .

I Have changed oil and filter changed coolant cleaned the tank out. Renewed fuel filters and cleaned the injector . It still runs lean with exhaust getting very hot within 10 seconds . I’m looking for advice .some say replace pump. Some say replace injector ??