Flat-track bikes are one of the purest forms of motorcycle. A frame, some short suspension, minimalist bodywork and even more minimalist brakes, and at the heart a thumping great thumper motor. Except racer John Roeder decided to do things a little differently…

Think flat-tracker and you invariably think four-stroke. Big V-twin Harleys, thumping great old air-cooled singles, or high revving modern MX motors blasting down the straights, tipping left, then sliding full lock in a graceful 180-degree arc. With the exception of one bike – Yamaha’s fearsome TZ750 made famous by ‘King’ Kenny Roberts – you don’t really associate strokers with flat-tracker racing. But when they’re lightweight, and pound-for-pound (both physically and financially) more powerful than a four-stroke, you’ve really got to wonder why not. John Roeder did…

Different Strokes

Originally hailing from Florida, flat-track has been in John’s blood from a very early age. Now aged 50, he’s been riding ‘roundy-roundy’ racers since the age of ten, when he piloted a 60cc Yamaha JT1. Moving up to a 100cc Kawasaki, John was soon riding three race meetings a week and at the age of 16 he was racing at AMA (American Motorcyclist Association) Pro level aboard 250 and 360cc machines. Unfortunately, this success was something of a double-edged sword, as the costs were becoming extraordinary. To really be competitive you had to be on a Harley (not something you’ll often hear outside of flat-track!) and, as John explained, ‘just one of their motors cost ten grand. And that was in 1979!’ At the time, John was racing a Yamaha against the Milwaukee machines and without serious sponsorship it proved hard staying on the pace. Top class racing proved prohibitively pricey, so John opted to give up on chasing a career in flat-track and instead joined the military.

A decade away from bikes ended when John was posted to Japan, where he rekindled his interest with an NSR250, and then Italy where he ‘got well into Ducatis’. But the flat-track bug only returned when John moved to Lakenheath in Norfolk in early 2005…

Spotting a poster for an oval track close to the airbase was the catalyst, and John was soon thinking about how he could build himself a bike. As the UK tracks are far shorter than those in the States he wouldn’t need huge reserves of power and John’s first idea was to base his racer around a Suzuki DR350 – reasonably plentiful, cheap, air-cooled and grunty – and rely on his flat-track race experience to get around the bike’s ‘straightline shortcomings’ compared to modern high-revving four-strokes. However, having acquired a DR it soon became apparent that the old trailie simply wasn’t going to cut it and even large amounts of tuning wouldn’t see it on par with a modern MXer. An old air-cooled Kawasaki KX two-stroke was considered before John set his sights on something a little more accessible – a CR500.

It took a year for John to find a CR5 motor that was both running and for sale at a reasonable price – he wasn’t looking to throw large sums of money at the project. On a trip to Qatar, one of the guys working for John happened to mention that he had a CR500-powered ATV for sale, so John acquired the engine and shipped it back to the UK. The bike then grew from the engine out…

A 1987 CR5 frame was bought from a bloke in Worcester though other than the fact that 500s are now commanding strong money, I wondered why John didn’t simply start by buying a complete bike? ‘A lot of the standard CR parts wouldn’t have worked for what I wanted,’ he explained. Whilst there are a lot of converted MXers in the UK flat-track scene, they look very much like lowered dirtbikes. And that wasn’t the style John was after.

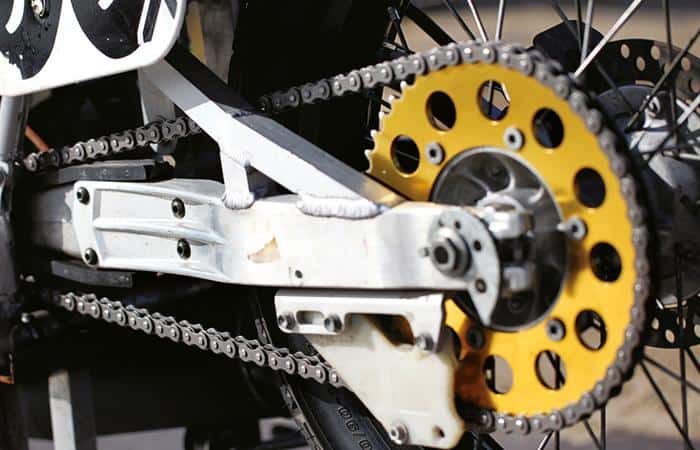

The main frame loop of the CR chassis was retained, and with the ’86 engine in place John needed to work on getting it rolling. The DR350 was still languishing unused, and it gave up its swingarm for the cause. Somewhat fortuitously, the swinger not only slipped into the frame/engine with minimal work but also gave the bike a wheelbase in the right ballpark.

At the front-end the standard CR clamps were used, and to make a set of FZR600 conventional forks fit John sleeved them with removable collets. Incidentally, these old Yamaha forks are soon to be replaced by a more modern pair from an R6, which will give the adjustability sadly lacking from the old legs. A 19in Honda CB750 wheel was initially added – early cast wheels being a good way to achieve a cheap 19in part, and they look surprisingly cool too – though as UK Shorttrack’s Thunderbike regulations allow wheels between 17-19in John is currently trying an 18in part from a Kawasaki Z1R.

At the back-end the DR350 hub was pressed into action, laced with a new rim to accept a 120-section Dunlop K180 Dirt Track tyre. This matches the same model tyre upfront, and both came via the late Gary Nixon, a flat-track legend in the US. Incidentally, as John’s now discovered, the front tyre is exactly the same as that found on Suzuki’s funky lil’ Van Van!

As with the rubberware, John used his knowledge of the American flat-track companies to obtain a rear master cylinder, rear brake lever and peg mounting plate from Go For Glass in Minnesota. (The pegs themselves are ‘homemade’ cut-down pillion pegs from the DR!) Parts such as the fully adjustable shock and catchtank also came from across The Pond, though aren’t exactly what you’d called traditional flat-track fare. ‘The shock came from Summit Racing,’ reported John, the company being a huge supplier of drag racing and performance V8 parts. ‘It’s a QA1 coil-over for some kind of hot rod. It cost me 150 bucks! And the catch tank is designed for a Chevy.’

John’s dad had taught him how to work out the required spring rate, so once the parts arrived he got straight into fitting the bargain rear shock. ‘I mounted it upright but the bike ran too high. It didn’t corner – wouldn’t tip-in.’ To combat the problem John over-braced the swingarm and laid the shock down, all the while making sure that the front-end geometry was maintained. ‘I was trying to stay under 25-degrees [rake]’, he explained. Atop the frame John fitted the beautifully-shaped Knight Racing Frames fuel tank and, on the homemade sub-frame, a slimline Champion Frames seat unit.

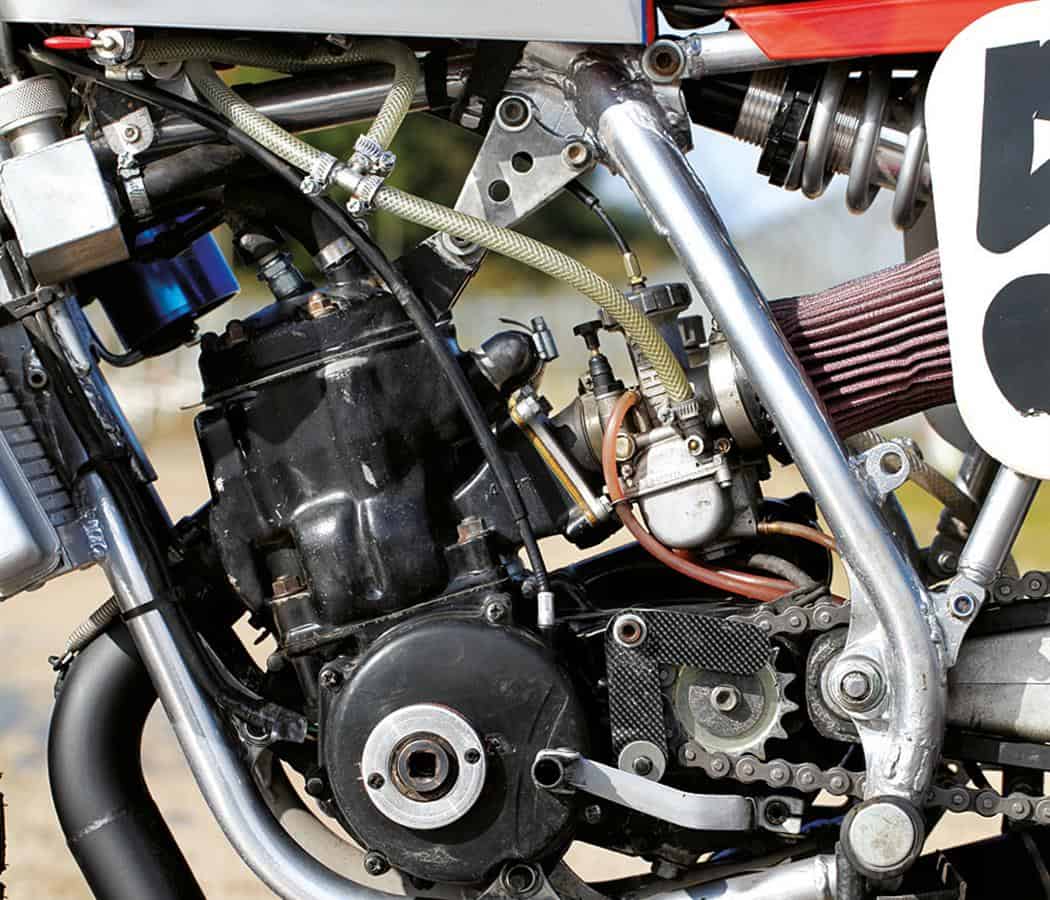

The motor itself has been left largely stock – ‘it’s got enough guts as it is’. The exception is the kickstarter. There isn’t one. The big CRs can sometimes be a little awkward to fire-up (or ‘ a pain in the ass’ as John put it) so rather than tire himself out kicking the thing into life before a race, he has devised another method to start the bike: he’s got a remote starter. Bought from the States, the device uses what John believes to be the starter motor from a Honda Civic, bolted into a frame and powered by a truck battery. John then obtained a drive for the starter to slot into from a different company, and fitted it to the flywheel. ‘The bolts to fit the starter housing cover wouldn’t clear the flywheel, so I used Ducati windscreen bolts!’ laughed John. A 916 sat in the Roeder garage, and various small parts were taken from it to further the build. ‘The more it sat there, the more I kept eyeballing its parts. You see those Dzus fasteners on the number boards? Yep…’ John doesn’t need to finish before I cut in with ‘you didn’t take them off the 916’s fairing?’ A wry smile sufficed for a reply. ‘I even considered flat-tracking that…’ he laughed.

By junking the kickstart mechanism the internal friction is reduced, though it also brings with it one small problem: if you stall, or crash, you can’t quickly restart the thing. This has really only manifested itself on one occasion, where the motor suddenly fell silent on the startline of a qualifying race. Fortunately, there was space on the grid in the following qualifier and the marshal let John push the bike to the infield and wait for that race. Bump-starting the bike simply wasn’t going to happen…

Induction-wise, the bike runs the usual CR5 Keihin carb and, as there’s no airbox, a K&N speedway air filter. Exhaust duties are taken care of by a Jemco exhaust. His previous flat-track experience led John to the Texan company, where owner Jon Easton enquired as to what frame he was running and on what type of tracks he was riding, before building him a pipe. Jon’s been manufacturing exhausts for over 40 years and has built-up a strong reputation within the flat-track scene. The satin black pipe on the CR is incredibly understated and very nicely put together.

Thus far there’ve been parts from a trailbike, an MXer, a sportsbike, and a couple designed for hot rods; so you’re probably getting a feel for how the build came together. John describes it as ‘an eBay Frankenstein’. It won’t be much of a surprise then to learn that the final part of the puzzle, the radiator, is from yet another different source – an Aprilia RS125. As it transpired, this alone wasn’t enough to ensure consistently reliable cooling so John tasked local firm Griston Engineering with fabricating a small expansion tank, which is tucked-up under the fuel tank, above the rad, on the left-hand side.

Sounds Different

Having spent a large part of the afternoon flicking through John’s photo album-cum-scrapbook of his old Stateside racing photos and press clippings I couldn’t leave without hearing the bike running, and John was only too keen to oblige. ‘I haven’t annoyed the neighbours in a while so it should be okay,’ he laughed as he opened the garage door to allow the fumes to escape and pulled the starter trolley over from one corner. The sound of the 500 spinning over was fairly raucous, though did little to prepare me for the aural barrage that soon followed.

The noise emanating from the Jemco exhaust was, and there’s no other words to describe it, pure evil. The pipe features little in the way of sound deadening, and whereas a bike with a regular dirtbike expansion chamber would sit there ringing and dinging, John’s bike cackled like a demented witch. ‘The first time I started it’, John chuckled, ‘finger-tight bolts flew everywhere when I snapped the throttle open..!’

Different Rider

‘This year there have been a lot of experiments. Whenever I make changes I see if they’ll work on raceday.’ John’s comment about testing initially sounds rather bizarre, as you’d really want to line-up on the grid with a fully sorted bike that you know is going to behave exactly as planned. Except with such a small pool of racers spread out around the country, and a limited number of suitable venues, organising test sessions and trackdays is far from straightforward.

So it was mid-race (or at the first turn, perhaps…) that John discovered the aforementioned problem with the ride height. And trying different sized wheels, and alternative tyres, had to be done whilst battling with 11 other riders.

It’s also no time to discover that the rear brake – the old DR350 part – isn’t up to the job of slowing a CR500 with no front stopper. ‘It’s crap!’ John laughed. ‘It’s definitely one thing that I will be changing this year.’ The wafer thin, drilled disc doesn’t look like it’ll take too much abuse, and thankfully John’s riding style didn’t rely on it too heavily. But after former champion Pete Boast took a few laps on the bike the disc had turned a vivid shade of blue!

Having built and developed the bike John’s now going to take a backseat and let someone else ride what he describes as ‘like domesticating King Kong’. Young up ‘n’ coming racer Tim Neave approached him about riding it and, as John put it, ‘that sounded cool to me.’ Check out this year’s short-track series to see how he gets on with it…

With one eye on performance and the other on a budget, John’s been incredibly resourceful in building the CR, using parts from varied, and often unlikely, sources to get the job done. Yet in no way does the bike look like the ‘Heinz 57’ that it is. It’s retained that stunning flat-track look, whilst at the same time being just that little bit different..!

The Oval Office

Thanks to Swaffham Raceway for the photoshoot location. The track plays host to banger racing, stock cars, and various ‘hotrod’ race classes (though no bikes, I should add). And if you’re there on the right day you might even get to see banger racing with caravans attached too. Oh, the carnage! For details and the race calendar visit www.swaffhamraceway.com

There are many more issues of RUST Magazine for your perusal just click on the link and enjoy! https://rustsports.com/issues/

If you’re into flat track check out RUST Magazine issue 28 for a feature of the Wheels & Waves event from Biarritz on the French Riviera. Click the link below…