In the first part the single-cam 450s did battle in the Rust Sports Shootout, this time it’s the turn of the 2011MY 450cc twin-cammers to go head-to-head…

There’s no doubt that if you want to extract high performance from a four-stroke engine, a twin-cam design is the way to go. Twin-cam engines produce fast-building power thanks to their ability to rev-up quickly – not least due to lower inertia in terms of the individual camshaft masses. The question then arises – do you need all the power they make, and will riders be capable of exploiting the type of power the engine produces?

Because while it’s nice to have plenty of power at your disposal, when it comes to riding off-road, having the optimal type of power available to match the levels of grip is far more important.

Ultimately it depends on the type of terrain you are riding. If it’s warm, dry and you have wide-open tracks at your disposal then the advantages of a twin-cam engine are very real – letting you exploit their superior rev potential. If on the other hand you mostly ride in slow or technical terrain, or the type of going where you’re constantly searching to find grip, then the marginally slower way that a single-cam machine builds (and transmits) its power can work to your advantage.

Cam Cam

Ever since the advent of the super-thumper back in 1997, it’s been the Japanese who have led the DOHC charge. It’s no coincidence that in last month’s (SOHC) test, European bikes outnumbered Japanese models, yet this month it’s the other way round.

So this time we have four machines on test – three of them Japanese, and one European. Two of the bikes are fuel-injected (Suzuki and Husqvarna) and three out of the four feature alloy beam frames (all Japanese), only one of them however, comes fully road legal and that’s the new Husqvarna, and that’s where we begin this shootout – with the Husky

As a marque, Husqvarna are making great strides at the moment in the off-road world. The UK importership has been taken over by the parent company and that has allowed the brand to expand country-wide in a way that’s never been possible before.

Of course the bikes were always sold nationally, but right now new dealers are springing up all over the country – placing their confidence in the revitalised brand. And it’s not just the importer that has changed, so has ownership of the parent company. Now in the hands of one of Germany’s most stable and profitable automotive institutions (BMW), there’s high hopes that the coming few years will not just see a return to stability and profitability for this passionate Italian concern, but also a flood of new models coming down the line.

And the first of those is the new Husky TE449. In fairness it’s not an entirely new model but more of a hybrid bike using the innovative – though rather unsuccessful – BMW X450 engine housed in a chassis of Husky’s own design.

Let’s get one thing clear right away, to stand any chance of commercial success with this bike, Husqvarna knew they had to address the intrinsic flaws that tarnished the earlier BMW incarnation. Those flaws included: the weird backward’s spinning engine that ‘felt strange’ to ride. The heavy and difficult-to-modulate clutch (due to its crankshaft positioning). The unyielding linkless suspension and odd geometry that made the bike difficult to turn. Not to mention an engine that felt too fierce at times and the strange co-axial output shaft that required you to remove the swingarm in order to change the front sprocket.

Husky have got form here, because the bike this one replaces – the old TE450 though much more conventional in design, was also considered too powerful and thus slightly difficult to ride.

So have Husky achieved their aims? Well for the most part I have to say, yes. An unusual ‘rocker’ linkage assembly operates the rear shock in a progressive manner and that appears to have transformed the (former) bike’s handling characteristics, and in particular the old bike’s lack of dive as you braked for a corner. And while the new bike is still very sensitive to set-up, and still ain’t the sharpest turner out there, it’s nevertheless greatly improved in this area – helped no doubt by rather plusher Husqvarna suspension than the immovable BMW units.

Moving on to the engine, the heavy cable clutch has been replaced by a more traditional European hydraulic unit. Suddenly the clutch feels light again and much easier to operate. Oh and the strange clutch sensation (that the Beemer had) of a long clutch pull has also largely disappeared.

But what about the backwards spinning motor? Well it may or may not be there, to be honest I didn’t feel the need to check because the ‘odd’ sensation you felt when riding it has vanished, to be replaced by a much more conventional feel. You simply don’t notice it. Husqvarna have added a sixth ratio into their gearbox and this has helped the Husky maintain the correct gear for the job, plus it gives a much nicer spread for trailriding.

And trailriding is where this bike will find doubtless its niche. Yes there may be a few good team riders campaigning the 449 right now in enduros (with good results I might add), but in our opinion this is a bike that better serves its dual-purpose role than almost all other 450s.

Because sensibly what Husqvarna have done is to reposition the bike – moving away from BMW’s hardcore racer into a much more rounded and vastly improved all-purpose machine. That means you can still compete on the 449 if you’re happy to hustle a 450, but more importantly it appears to have been built with a much broader remit in mind.

Imagine the easy-going nature and well-specced quality of a KTM 450, now notch up the plushness a level – key ignition, smoother engine, EFi, higher quality switchgear, flatter seat, starship styling – and you end up with the Husqvarna TE449.

True it doesn’t quite cover ground in the same way as a KTM – in fact it’s comfier, arguably as plush but slightly more remote. And the twin-cam engine is much smoother in its operation, but the payback is that it doesn’t hook up in the same way that the EXC does – at least not in snotty conditions. You can’t have everything. What the Husky does do though is cosset you nicely from the underlying terrain whilst remaining eminently stable over broken ground. Riders coming from a roadbike background are going to like that feeling.

Hop aboard and it feels slightly different from most other 450s. Like the BMW X450 before it, the seat is flat (though much comfier than it was on the Beemer), and like the BeeEmm the Husky stores most of its fuel under the seat towards the rear of the machine – accessed by an oddly angled fuel cap located at the junction between the rear of the saddle and the rear mudguard (perfectly positioned for lumps of mud that are stuck to the seat to drop into the filler neck when you fuel up).

On the flip side it means that there’s nothing in terms of petrol tank located between your knees. Instead, the front part of the bike is reserved for the location of the slot-in air filter (much the same as it was with the BMW). Now this is the ideal place to position an air filter (up and out of the way of water), but it’s definitely not quite as quick or easy to access as the flip-open side-panels on other 450s.

As you would expect for a bike with no front mounted fuel tank, the riding position is good, with a forward bias and this helps place lots of weight over the bars and onto the front wheel – which is just what you want in order to pin the front of the bike down and make it turn.

The Husky exhibits plenty of stability at both low and high speeds which is confidence inspiring, but it’s not the kind of bike you’d want to try and flick-flack between trees with any great urgency. Yes it’ll do it, but other bikes here are quicker – most noticeably the RMX which we’ll turn to next.

Yellow Hammer

Here at RUST (Previously TBM) we have a bit of a love/hate relationship with Suzuki’s latest 450 (elsewhere you can read about what’s happening with our long-term machine). We still believe that the RMX450 is fundamentally a brilliant bike. Underpinning that belief is the knowledge that this machine has a stonking engine and a great-turning, lightweight chassis. However certain features of the bike, most notably the suspension and fuel injection give us cause for concern.

We had originally expected to be testing a 2011 RMX in this shootout, unfortunately at the last minute, Suzuki weren’t able to provide one for test and so we had to resort to using our own 2010 bike. So I’m not able to confirm whether they have sorted the suspension and fuelling issues on the new models. What I can say with certainty is that there’s a helluva’ good bike in there waiting to get out and play, but it does need finishing.

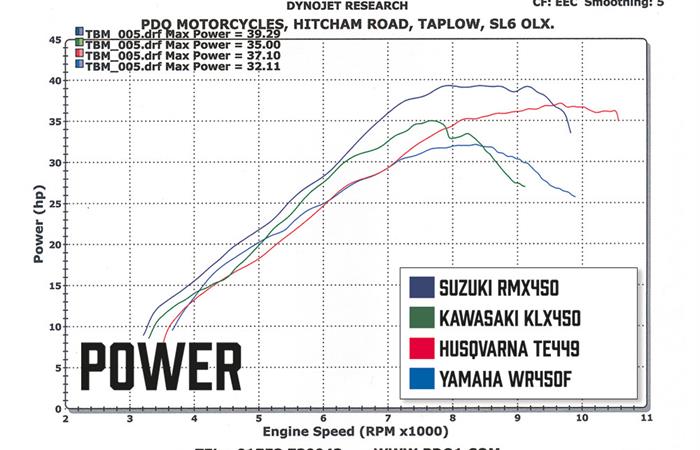

How good? Well let’s take a look at the dyno charts. The Suzuki runs out the most powerful of all the machines tested here – and by some margin – recording a figure of 39.29hp. I should qualify that while the bike was pictured with the aftermarket exhaust, we actually dyno tested it with the stock system in place, albeit after it had been slightly modified by Suzuki. If you’re worried that that adds a margin of error into the equation then I don’t blame you. We try to even things out as much as possible (in terms of keeping bikes stock) but we can only work with what we’re given.

For the record the next most powerful was the Husky – once it had been fitted with the stock/alternative Akrapovic that comes with the bike in the box. Although a non-Euro-homologated pipe, it still easily complies with current enduro regs in terms of noise output, but isn’t constrained by a power-sapping catalytic converter (in other words it’s got the kind of exhaust that KTM fit to all their bikes during PDIing). Fitted with this exhaust the Husky gave a best reading of 37.1hp

Believe it or not, next up was the KLX450 making 35hp dead. It has a pea-shooter exhaust that utterly strangles its top end. And interestingly all of these bikes make less power than we achieved from equivalent models a few years back. Our suspicion is that this situation has come about as manufacturers try to meet ever-more stringent noise regs using existing machinery. And truth be told we think that’s a price worth paying.

Finally (and hard to believe it when you ride the bike), comes the Yamaha WR450F with a modest power output of 32.11hp from its heavily strangled pipe. Not that it feels like it when you ride it. The bike positively hauls out of corners when you twist the throttle, but the dyno doesn’t lie.

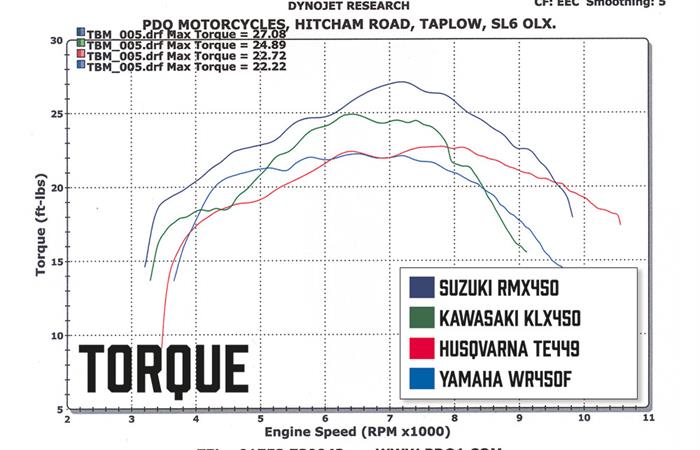

The figures for torque were arranged in a broadly similar way with the Suzook eclipsing everything across the entire rev range. The Yamaha’s curve spiked earlier than most (at 4500rpm) and it carried on making decent shove for the next 4000rpm. The Husky had the smoothest curve of all with a steady progression of power from 3,500-10,000rpm and finally the KLX torque curve was lumpier than school mash, though it aces both the Husky and the Yam overall.

The actual figures we recorded were 27ft-lbs for the RMX, 24.9ft-lbs for the KLX, 22.7ft-lbs for the Husky and 22.2 for the WR-F. How does that compare with the SOHC machines we tested last month? Well interestingly the twin-cam Suzuki is the overall winner on torque, though in general it was the SOHC bikes that were slightly torquier overall.

When it comes to power it was actually the single-cam KTM that took overall honours, making just over 1hp more than the DOHC RMX! That was a turn-up for the books. Five out of these seven machines were making upwards of 37hp with just the KLX and WR-F falling below that figure. And we’re certain that in their cases the standard exhaust systems were holding them back. However it should be said that none of these 450s felt slow to ride! Now back to the RMX.

Putting aside the fuelling (starting/stalling) issue for one moment, the RMX is actually a great bike to ride notwithstanding the fact that the suspension appears to be incorrectly specified for the weight of the bike. It’s as if they took the spring rates from the latest RMZ450 motocrosser and cross-pollenated them with the valving from the old DR350S. What you end up with then is a harshly sprung but softly damped machine that threatens to get seriously ‘uppity’ once the track becomes bumpy.

Which is a great shame because with its marvellous riding position and thrilling engine the RMX deserves a chance to shine, but it takes a brave rider to properly exploit this machine on stock suspension. We know the bike’s capable of better things (it won the BEC E2 class in its first year of production), so for those of you looking for a 450 racer, who are prepared to invest a bit of time and effort it’ll reward you with a genuinely competitive mount. It turns brilliantly, feels light and is very chuckable (thanks to that flat perch and tiny – but rather useless – 6.2L tank), and the motor is astonishing in terms of its punch.

But as a trailie I suspect most riders will find it too fierce in its response, too harshly suspended, too short on range and frankly too much trouble. Obviously it has no trail/road kit fitted so that’s another cost the dual-sport rider will have to bear. And for those who don’t want the hassle of having to ‘sort’ their bike I would advise they steer clear of the RMX.

Green Manalishi

Every time we ride Kawasaki’s KLX450 we come to the conclusion that it is a bit of an oddball. On face value there’s much to enjoy about the big Kawa – not least its competitive pricing amongst this crowd. In all honesty, it reminds me of a great big Labrador puppy that just wants to play with you all the time – all joyous enthusiasm and full of loopy fun. The motor feels incredibly peppy thanks to a ferocious bundle of torque that provides power on demand, whilst the chassis, suspension and brakes are all up to snuff and typical of what you’d expect on a decent Japanese 450 – so far, so good.

However….. now we come to the less likeable stuff. For starters it looks like a Duplo bike – the styling is horrible – truly awful – the plastics are cheap-looking, the tank appears to be an afterthought and the dials are just a bit clunky and, well… clumsy. But the biggest problem with the KLX is one that’s much harder to ignore. And that’s the yawning chasm between first and second gear, which is bigger than the gap between a teenager’s way of thinking… and everyone else’s!

First is like a crawler gear – too low for anything but trialsey type stuff – but shift up into second and you’ll need to slip the clutch if you want to negotiate ruts and the like. In between lies no-man’s land. I realise it would be possible to lower the gearing to effectively make first gear obsolete but then you’ll run out of speed at the top-end. Conversely if you raise the gearing to bring first gear up to a sensible ratio, then a useful second gear will be absent and it’ll be like shifting from first to third. I recall we mentioned this when we raced the bike last year.

If that sort of thing doesn’t bother you then celebrate discovering a sturdy, reliable, powerful, knockabout Japanese 450 thumper that’ll wheelie on demand and provide you with reliable enjoyment. The motor’s got oodles of torque available so you’re never stuck for power, and the bike’s actually a decent handler – notwithstanding the fact that the Lego pyramid tank won’t let you get anywhere near the front of the machine. On the plus side it does offer decent range to the trail rider.

Most of the time you don’t notice the gap down to first gear because the bike’s happiest pulling taller gears thanks to the motor’s bountiful torque. But if you like to take in a bit of nadgery going when you ride, then you’ll find this facet of the KLX infuriating.

Also there’s no road/laning gear fitted as standard, but that’s typical of the Japanese. In the final analysis it’s fun, fast and affordable but also slightly flawed. Shame.

Blue Flame

Yamaha’s WR-F is normally the rock solid performer in 450 shootouts. If it’s dry then nothing will touch it around a track, but if it rains it generally turns into a fishtailing liability – all thanks to what feels like a surfeit of horsepower. And had we not put these bikes on the dyno, then I’ve no doubt that’s the conclusion we might have drawn this year. Because riding it, the WR-F FEELS deliciously fast around a track. It doesn’t have the same explosive midrange corner exit speed as the Suzook – or Kawasaki for that matter – but the jetting is so crisp and the power delivery so linear that the Yamaha simply rails the turns thanks to near-perfect throttle precision. Fuel injection may be the future, but when a bike carburetes this well, you wonder what’s the point.

It’s not quite as nimble as the Suzuki, however, the chassis feels more stable by comparison (providing it’s not overly bumpy), leaving you feeling much more in control. But then the whole machine feels a bit less exciting to ride than the RMX. Albeit one man’s excitement is another man’s ‘liability’.

The suspension worked better at slow and moderate speeds, than it did when the bike was being flogged, but overall the balance felt fine and there’s plenty of adjustability to suit riders of varying weight and ability.

But where did the WR-F’s horsepower go? We didn’t believe the first couple of dyno runs – we had to repeat the process (having checked the tyre pressure again), to ensure we hadn’t made a mistake. But we hadn’t. Our WR-F really did ONLY make 32hp. All I can say is that the dyno doesn’t tell the full story, because the bike felt considerably faster than that.

Like all recent Yamaha’s this one is not only well put together, but feels like it would last a lifetime too. The quality of the plastics and other details is a definite notch-up on anything else here, bar the Husky, and it’s easily the best of the Japanese trio. The motor feels utterly unburstable and experience has taught us that ‘investing’ in a Yamaha (and with bikes costing north of 7k, it really is an investment), is ultimately a sound financial decision. Payback comes in terms of reliability, dependability and resale value. They may cost a sight more to buy, but these WR-Fs are as dependable as the tide.

Snog, Marry, Avoid

So add them all into the mix, shake up a little and what have you got? Well it’s a slightly odd-flavoured cocktail that’s for sure, but there are elements here that are worthy of further tasting. Things like the Suzuki’s front brake (though not the rear one), the Husky’s plushness, the Yamaha’s build quality and the Kawasaki’s sheer midrange punch.

We all loved the way that the Suzuki launched out of turns and held a good line through them. What was more worrying was its inability to start on demand, and the fact that the suspension could be seriously scary at times. It’s a really good bike the RMX, but in our opinion it’s not quite finished.

Aside from the Kawasaki’s gear ratio issue, there’s nothing much wrong with the KLX that couldn’t be cured by a decent restyle – preferably by the bloke who designed their MX bike, but failing that we’d settle for someone who doesn’t require the services of a dog to help him find the post office. It’s disappointing to see that even Kawasaki’s UK-supported enduro riders have given up on the KLX and opted instead for the MX bike. That alone should tell you all you need to know about the machine. Truth is it’s a good, honest bike that’s a damn sight better than it looks. Which given the way it looks is not all that surprising…

Ah the trusty WR-F, actually a bloody good bike. It rarely wins our 450 shootouts but it’s always right up there among the best. This year it actually felt a lot easier to ride, but that’s only because it was down on power [you see what we did there, we gave with one hand and took away with the other!] The fact is that the WR-F is easily the best of the Japanese bikes – despite a horsepower disadvantage – because it’s so well sorted and engineered. Not surprising really, it seems to have been around since God were a lad and Yamaha continually invest a lot of time and resources into developing their models. One thing’s for sure if you buy a WR-F you’ll be able to sell it again further down the line which is more than can be said for the Suzook or Kawa at the moment.

So where does that leave us – ah yes, the Husqvarna TE449. The newest bike here, the least conventional bike here, the most complex bike here, and also the victor in this twin-cam part of our shootout. It’s not necessarily best or even better than the others at everything it does, but what it does bring along to the party is evolution, sophistication and all-round usability.

It is the ONLY one of these four that comes fully equipped for street, trail AND race use. It’s by far the comfiest, by far the best equipped, by far the smoothest and by far the most modern looking. The motor is strong yet civilised, fuel-injected yet smooth on the uptake, economical and quiet, yet nicely potent.

True, it’s more of a fifty/fifty, trail/enduro machine than a thinly disguised racer adapted for the road, but is that really a criticism? Given the age profile of the average 450 buyer we’d actually consider that more of an advantage. Yes at the heart of it lies a BMW engine that no-one seemed to like at first, but Husky have tamed it and trained it and turned it into a beautiful dual-sport bike for the cognoscenti and for that alone, as well as its sheer head-turning looks, we have to declare it the best of the twin-cammers…

450 SOHC and DOHC Shootout. And the winner is…

And so inevitably it had to come, the final decision on who makes the best 450 of 2011? So step forward the KTM 450EXC and the Husqvarna TE449 as winners of their respective shootouts. We got them together once again to go head-to head…

I’m not going to draw out the result as we’ve already written extensively about both bikes. Suffice it to say that the clear advantages the Husky enjoys over the Japanese machinery, it can’t quite claim over the KTM. For instance both Euro bikes are well put together, both are extremely well specified (though the Husky is slightly better in this regard than the KTM, offering a choice of pipe, nicer switchgear, electric fan, EFi, key locking etc), and both are fully trail legal.

True the Husky is more interestingly styled, and has quite an innovative motor, and we like its sensible features like the positioning of the raised air-filter, the flat seat and the security of key ignition. But when all’s said and done the KTM is the better off-roader. And that’s the point, isn’t it?

And although the Husky makes the better road bike of the two (truth be told most trail riders spend far more time on the road than they do on the lanes), that’s not really the deciding factor. If I were to expand a little more then I’d say that if you’re coming into the sport from roadbikes where the machinery is much more sophisticated, much smoother, and far better equipped, then you’ll likely feel much more at home on the Husqvarna. It offers an excellent transition between road and dirt without the compromises normally associated with a heavy road-biased trailie. It’s also a competitive enduro bike.

But if it’s a pure dirt bike you’re after then the KTM has to be the pick of the 450s. Look at it this way, it’s the most powerful of the seven we tested, yet has arguably the easiest-to-use power delivery of all the machines. Its chassis is beautifully suspended – supple and plush for slow speed riding, yet firm enough to take the hits when speeds increase. It’s fully equipped for both street and competition use, and KTM’s quality, performance, competitiveness and residual values are well proven in the marketplace.

And most importantly of all, as this SuperTest has proven, It has the drive and rideability of a single-cam engine, with the performance to better even the best twin-cammer. Ladies and gentlemen I give you the worthy winner of TBM’s 2011 SuperTest450s… the KTM 450EXC!

Thanks to the following, without whom this test wouldn’t have happened:

• Boss Hog at Enduroland for the use of the track. Enduroland run enduro practice days at a number venues throughout the country – from Fife to Somerset! Along with these regular ‘trackdays’ they also offer days for ‘kids and dads’ plus novice riders. You’ll find full information on enduroland.co.uk and you can get the lowdown on forthcoming events by calling their info hotline on 07564 255718. www.enduroland.co.uk

• Nick and Larry at PDQ (01753 730043) www.pdq1.com for the dyno time.

• Craig at Azcari for the loan of his box-fresh TE449. The Azcari Adventure Centre is an all-new dealership opening in Dorking, Surry, on 9 April and along with Husqvarna bikes they’ll also be stocking products from Kriega, Klim, Touratech, Satmap, Venhill and more! Visit www.azcari.com or call 01306 646424 to see their

• Luke at Suzuki www.suzuki.co.uk

• Dave at Husqvarna www.huskymoto.co.uk

• Martin and Ross at Kawasaki www.kawasaki.co.uk

• Simon and Karl at Yamaha www.yamaha-motor.eu

• Geraint, Dylan and all at the Yamaha Off-Road Experience www.yamaha-offroad-experience.co.uk

• Rich and Ross at KTM www.ktm.com

Second Opinion

I’ll cut straight to the chase. The Kawasaki didn’t really do it for me, with the motor feeling a little too cammy and the entire package failing to excel in any one area. If you bought one and never rode any other 450 you’d probably think it was fine, but in the company of other machines it singularly failed to impress.

Putting aside our Suzook’s stalling/starting issues, the RMX has a lovely slim feel to it and a very strong motor but the suspension doesn’t allow you to make use of that power. Like the Kwaka, I merely found it ‘okay’.

I’ve never really gelled with the WR450F as the big Yam has always been something of a straightline rocketship. This one was mellower, yet still romped out of corners with real gusto. The problem was it wasn’t as nimble as the Suzuki, nor as smooth and stable as the Husky. I’m still not a big fan…

On its launch last year, I didn’t get on with the TE449 as it seemed hard to get it turned into slow speed corners and felt too big and too fast. Little’s changed. However, riding it against the Yam, Suzook and Kwaka has highlighted just how well it plays that ‘smooth and civilised’ role. In almost every respect the Husky is more refined than the other bikes and therefore it tops the twin cams for me. I still wouldn’t want one for racing enduros tho’..!

Which only leaves me to pick an overall winner, and that has to go to KTM’s 450EXC. So light; so quick-turning; so easy to use; yet so amazingly fast. It’s everything I want from a 450… Barni