There’s something about Italian race machinery that takes your breath away. RUST takes a spin on the new TM EN250 and discovers a special breed of bike…

Back in the mid Eighties I was a fan of rallying. There was nothing quite like standing in a soaking wet Knowsley Safari Park watching the efficient and devastatingly quick Audi Quattros battling with the stylish and elegant 2WD Lancias. It wasn’t just a visual treat, it was enough to make the hairs on your arms stand on end. I loved the Audi’s competence, the way its mechanical and technological advantage had been arrived at, and the way it put its clinical excellence to work dispatching a slippery special stage. But for all its teutonic efficiency, it was the flamboyant underdog Lancia team that really appealed to me. Enough to make me consider searching out a Lancia Monte Carlo and a Lancia Beta Coupe in the classifieds, though in the end I settled for a succession of fourth-hand Alfa Romeos and a quintessentially-Italian Fiat 124 Spider.

The great Audi versus Lancia rallying battle is long gone, however you could argue that today it’s being played out in microcosm in the dirt bike world with the all conquering, uber-efficient KTM team being challenged by the plucky Italian squads from Rimini and Pesaro in the form of Husqvarna and TM (though of course Husky are now under German ownership, so that really just leaves the TM team).

You don’t see many TMs in RUST. Partly it’s because as a dirt bike manufacturer, TM is tiny compared with other brands. Partly it’s because getting hold of a TM press bike can be tricky due to limited availability. But mostly it’s because not many TMs are sold in the UK. Put simply, TMs are about as popular as Lancias. Though at least there’s a UK importer for TM which is more than can be said for the luckless Lancia brand.

Why should that be? Well, for one thing they’re expensive. Not stupidly expensive (or even that much more expensive than anything else), but they’re at the top end of the price spectrum in terms of their competitive rivals. And the other – rather more pertinent – reason probably comes down to the fact that the TM brand has always existed (since its inception in 1976, anyway), as a racing-focussed company. Nothing more, nothing less. And as such their products are seen as ‘no compromise’ machinery.

Nothing wrong with that, especially if you just want a bike to go racing with. But these days most consumers expect more of their machinery; and where brands such as KTM and Husqvarna have gradually softened off their products from the hardcore, pure competition machinery it used to be, to producing bikes which manage to combine a high level of user-friendliness with super-competitive abilities, TM make no such concessions with their products. Yes, their bikes are road-legal as they need to be for enduro competition (and they’re electric-start), but the focus is on racing first and foremost. In many ways TM’s ethos is broadly similar to that of Husaberg before the Austrians purchased the brand and turned it into the desirable, manageable, yet still competitive machinery it has become.

Talk to those who know the two men who founded (and still own) TM, and they will tell you that they have racing in the blood. Sales volumes are an anathema to them – they strive for a pure product which excels at its proposed discipline. And rather like Husaberg, this has enabled this tiny Italian manufacturer to punch above its weight in terms of racing success. In all the disciplines in which they compete (enduro, MX, supermotard and kart racing), TM have enjoyed comparatively more success than you might expect, given their size and limited resources.

Blue Blood

So what of the 2010 TM EN250Fies – what sort of bike is it, how does it fit into the enduro firmament and what are you actually getting for your money? Well first of all you are getting the only all-alloy-framed European enduro bike currently in production. That’s right, TM may be small as a company, but that doesn’t mean they have to compromise on quality. Their handmade alloy frames are beautifully built and… if they bear more than a passing resemblance to a Honda CRF well… let’s just say that it’s no co-incidence. Honda are renowned for their fine handling machines, and not to put too finer point on it, TM have simply borrowed some of Mr Honda’s expensive R&D and then applied it to their own bikes. Job done.

So it handles like a Honda, but it’s powered by an engine which is all TM’s own design – more or less. The gorgeous sand-cast, twin-cam engine shares the Yamaha WR-F’s 77 x 53.6mm bore and stroke (the four valves being actuated by finger followers in the style of a KTM), but unlike both the Yamaha and KTM, the TM is fuelled by a (largely) Kokusan digital electronic fuel-injection system. This gives the bike instant response and must be partly responsible for the TM’s incredibly smooth power delivery.

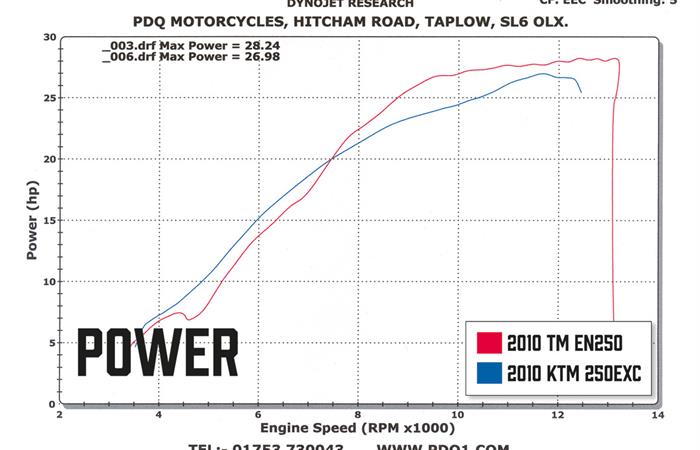

Now when we talk about ‘smooth power’ in this context we’re not referring to a lack of vibration from the alloy engine. On the contrary, the TM’s engine is hardly the silkiest out there. No, what we mean is that the power delivery is very linear. How linear? Well take a look at the dyno chart and you’ll see what we mean. By way of a comparison we’ve superimposed the TM’s dyno chart with one from a 2010 KTM 250EXC-F that we measured a few months previously and where the KTM’s dips and rises then climbs rapidly, the TM just gradually goes on producing more power at a sequential rate, peaking at around 12,000rpm. And although the EXC makes slightly more power overall (28.2hp compared with 27hp for the TM), it does it in a way which is much less predictable. For instance where the KTM dips at 5000rpm, the TM is still pulling strongly and smoothly through its midrange and indeed out-punches the KTM up to about 7500rpm. At that point the lines cross and the KTM takes over in the power stakes. Comparing torque curves is even more revealing: the beautiful linear delivery of the TM appears incredibly smooth compared with the troughs and peaks of the Austrian bike.

And you can feel this when you ride the bike. Exiting a smooth but off-cambered, uphill, grassy corner in second gear, I was able to really feel for grip and as soon as the tyre had purchase, I could open the throttle and the front-end would climb in the air… and stay there! Open the throttle a fraction more and she came up an inch or two, close it slightly and it went down a corresponding amount. Aside from making the TM a brilliant wheelie bike (which is irrelevant), the importance of this is that it lets you accurately dial-in precisely the amount of throttle required at any given point, and/or vary it accordingly. It also means that wasting time and power with wheelspin can all but be eliminated in the dry, which is obviously what you want of a race bike. Superb.

Is it a coincidence that the TM is fuelled by EFI whereas the KTM is still on a carb? I think not. The TM’s electronic fuel injection is a combination of TM’s own design and Kokusan parts, and it works brilliantly, from bottom to top. In fact the only time I could make it miss a beat was when gooning around for the photos – stuffing the TM into a slow corner and then blasting open the tap full throttle would occasionally (and I do mean just occasionally) cause the engine to load up and stall. I’m guessing the fact that TM have chosen a gigantic 44mm throttle body to feed their bike may have something to do with it, but don’t worry it’ll never happen in day-to-day riding.

What you do get however is crisp, seamless torque from the moment you open the throttle until the engine stops singing at 12,000rpm, and the best part of all is that it feels so useable. With a similar amount of power at your disposal as a Yamaha WR250F, the TM covers ground fairly rapidly but never feels scary or awkward in your hands. That’s the beauty of 250 four-strokes, they’re just brilliant fun to ride, and the TM is one of the best. Not quite so enjoyable was the TM’s slightly notchy gearchange and slightly heavy clutch pull, however. Neither were particularly bad, but both were noticeable compared with the stuff we’re used to getting these days. On the plus side the TM is an easy-starter, whether on the button (first time) or the slightly high kickstart (with auto-decompressor), our machine never failed to fire up easily – hot or cold.

Blue Grass

But if the engine is enjoyable to use, it’s the chassis and cycle parts which really marks out the TM from virtually every other bike out there. But before I get into details about how and why that is, I have to mention that the bike we rode was Phil Mclaughlin’s machine – the one he’s been campaigning in the E1 Championship class of the BEC this year and at the British Enduro Sprint Series. Not only is Phil a faster rider than me (and most people come to think of it), but he also likes his bikes set-up in a very specific way. HARD! No, scrub that, hard doesn’t even begin to do justice to the firmness of the set-up we encountered on Phil’s bike. Like most serious riders he gets the bike revalved to his own specification, so while we adjusted the clickers on the 50mm Marzocchi forks to make them a little softer, we really didn’t want to mess up Phil’s settings. Instead we just rode the bike in its ‘hard’ state and got on with it.

And you know what… despite its teeth-rattling firmness it works like this. I’m convinced this is down to the TM’s race-bred characteristics. It’s funny, but the firm set-up didn’t seem to upset the bike at all – and unlike with, say, the Gas Gas EC2504T we tested last month where the firmness of the ride seemed to be at odds with the plushness of the rest of the machine, with the TM it just makes the bike feel so cohesive and planted and set-up for high-speed racing, that you just want to thrash it everywhere you go.

But here’s where the TM feels different to every other bike out there at the moment. Forget the rock-hard (non-standard) settings of our test bike, every single part of the TM’s chassis and cycle parts is set up for racing. The steering from the giant 50mil forks set in forged triple clamps with 22mm off-set is utterly precise. You feel every bump, every stone, every tiny movement of the front wheel, not just through the bars but through the whole machine. Those of you who have ever driven a proper racing Kart or race-car will know what I mean when I say that it’s the difference you get between a rose-jointed feel, and the slightly woolly feeling you get from a fast road car sat on rubber bushes. It’s not the firmness, it’s the precision and feedback you feel all the time with the TM. Through the rock-hard seat, the giant flat pegs and the tall braceless bars – I see now why TM don’t recommend their machinery for trail riding.

This feedback lets you be very precise with the TM and position it where you want it – which is just as well as the bike doesn’t feel like the smallest of 250s. It’s funny, the deadly accurate electronic RUST scales recorded its weight at a smidgeon under 114kg (without dials – removed by Phil), which makes it among the very lightest machinery out there. It’s about a match for the new ultra-light Husky – lighter than the Yam, Honda and Gasser etc. In fact only the KTM is lighter still (by less than a kilo), and yet for all its lack of mass the TM never feels featherweight in your hands. Instead it feels sufficiently light yet very planted – it doesn’t shake its head nor do anything weird, and in some ways it handles like a slightly larger machine. I think part of that is down to the firm suspension making it sit higher in the stroke at all times, partly it’s due to the very tall bars which position you high and upright, and partly it’s thanks to the TM’s ‘Honda’ geometry which makes it incredibly stable on all types of terrain.

Get it onto a grassy test with flat turns and you will be amazed by the TM’s prowess. The brakes (Nissin master cylinder feeding a Brembo caliper up front, Nissin system at the rear) are unbelievable. You can leave your braking till the very last moment, slam on the anchors and still get the thing stopped in time for a corner – even if it’s bumpy. With a superbly deigned, slimline (and low) tank, together with well-designed narrow rad panels letting you climb all over the front of the bike, turning in couldn’t be simpler. And throughout the radius of the corner the TM feels utterly composed and settled into the track no matter what your angle of lean (though it’s not the most agile through the turns – KTM still takes that accolade). Then, on the way out you wind on the power, shift your weight towards the back of the seat and point it at the next corner, and the TM just hooks up and drives – no bouncing, no shimmying or wild oversteer, just forward motion. Brilliant.

Whether it would feel quite so good in a slippery woods section with exposed white roots and deep ruts I can’t really comment, because although the stability would work in your favour, the firmness of the whole bike might not. We did find some woods to ride in and rather surprisingly the TM turned out to be excellent at feet-up riding, but we couldn’t re-create wet Welsh conditions in the heart of SE England in summertime.

Loose surface going with stones, sticks, and loam are sensory overload. The amount of feedback you get from riding the TM threatens to overwhelm you at times as you feel precisely what both ends are up to. But once you get your head around the bike’s feel, you quickly learn to process the information and use it to your advantage.

The Blues

One of the things you do notice with the TM is that all the R&D money has been spent on making this bike work for racing, so that there’s nothing left to correct little design niggles. Niggles like the rear end of the bike’s tank panels (just beneath the seat) vwhich catch and trap your riding trousers at times. Niggles like the bodywork which (at the rear especially) vlooks slightly dated and awkward to clean underneath. And there’s no getting away from the fact that this bike has an engine which is designed and built in house. Lack of vibration, is obviously pretty low on TM’s list of priorities and it’s accentuated all the more by the continuous amounts of feedback you get through the bike.

Blue Motion

So, in the TM we have a very taut, lean, racing machine – no more no less. And despite its narrow focus approach, it’s not like you can guarantee racing success by investing in the TM. You can’t. What you can do however is to ensure that you are buying a bike which is utterly race-ready and capable of winning races right outta the box. I reckon that my own levels of fitness would allow me to race this bike for three hours (at H&H speed), but no longer than that – such are the demands that the TM places on you, by virtue of its single-track approach. If you’re young (under 40), fit and competitive, then the TM would make a suitable alternative to the hordes of orange and blue bikes out there. And it’s different.

Achingly beautiful, it demonstrates that you’re either serious about your racing, or a fan of fine, Italian race-bred machinery. Either way, that’s gotta be worth at least 20sec a lap in the paddock alone. I can also see that there will be a small section of our community who may well be over 40 and not all that fit, but just like the idea of parking a bit of Italian ‘exotica’ in their garage. Why not? The TM is in no way difficult to ride, on the contrary it let’s you know what it’s doing at all times. But it’s not a sit-down-and-twist-the-throttle type machine. It’s the type of bike that demands to be ridden. And ridden hard if you’re to get the most out of it.

One other thing worth knowing – TM’s may be fast but they’re not fragile. The factory has a reputation for making solid machinery that’s not only lightweight but also incredibly strong. This is not a super-fragile piece of exotica that will grenade if you forget to change the oil one time, or smash into a million pieces during your first tumble. Look closely at the pictures and see the way the TM is built, the way they tuck in the header pipe (unlike virtually all other manufacturers), the way the frame and engine looks strong. It’s a bike that’s built to last, but it’s not a put-it-away-wet machine, in the style of a Honda XR.

Blue juice

If you want a do-it-all type of machine that you can take trail riding or even take to the tarmac at times, can I steer you towards the Husky or the KTM, or perhaps the Yamaha or Honda 250. All these bikes offer far more versatility than the single-minded TM. They are plusher, arguably easier to ride when you’re tired, and certainly more versatile when it comes to using the bike on the trail. The TM however is not a trail bike. If pushed it can turn its hand to it, but if trail riding is your bag then give the TM a wide berth. Nope, the TM is an amazing little race bike: the sort of bike which instills you with pride-of-ownership, and teaches you about the joys of racing. It’s special in a way that the more mass-produced bikes can never be.

These days you’re spoiled for choice in the 250 thumper market and there are some great little machines out there. But only one of them will make your hairs stand on end like the sound of a Lancia 037 on full chat. The Audi may have won more titles, but the Lancias won my heart…

2010 TM EN250i es

Price: £7095

Engine: DOHC, fuel injected, dual start, four-stroke

Bore & stroke: 77 x 53.6mm

Displacement: 249.46cc

Transmission: 6-speed

Frame: Alloy beam

Front susp: 50mm Marzocchi USD fork, fully adjustable

Rear susp: Ohlins shock

Front brake: 270mm floating Braking disc, two-piston Brembo caliper

Fuel capacity: 8.2L

Weight: 113.9kg (wet, as tested without clocks)

Contact: TM UK on 01249 715523 www.tmukonline.net

SECOND OPINION

Back in 2007 I had a TM long-termer. Like this one it displaced 249cc but seeing as it was a steel framed stroker rather than an alloy chassis’d thumper you’d think that the capacity would be pretty much all it’d have in common with the new machine. Not so…

Firstly the suspension was firm and it handled wonderfully predictably. Maybe the chassis wasn’t quite as taught as the ally-framed bike but it was still decidedly racey – fast going and hardpack terrain proved an absolute joy.

And whilst it too was intrinsically as strong as an ox, you needed to spanner it with some care because, like the 2010 bike, all of the fasteners were super-light, super-soft alloy and super-easy to round off!

Despite some slightly dated styling the bike also drew admiring glances the second it was wheeled from the back of the van and became a talking point at every event we took it to. I’ve no doubt that the four-stroke would do likewise.

Yet perhaps the biggest similarity is in the power characteristics. That sounds bonkers at first, especially given the abrupt power delivery of a two-stroke and the fact that it was producing nigh-on 50 percent more go than the bike you see here, but its linear delivery meant that it was eminently rideable. And that’s just how I found the four-stroke. Because whilst the chassis deals with what happens when you’re riding it as hard as you dare, it’s the easy-to-access power which gets you up to speed in the first place… Barni